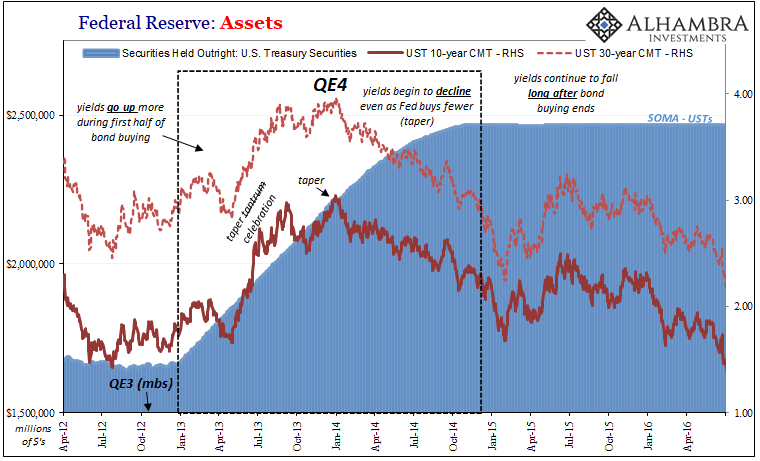

| We’ve been here before, near exactly here. On this side of the Pacific Ocean, in the US particularly the situation was said to be just grand. The economy was responding nicely to QE’s 3 and 4 (yes, there were four of them by that point), Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke had said in the middle of 2013 it was becoming more than enough, creating for him and the FOMC coveted breathing space so as to begin tapering both of those ongoing programs.A full and complete recovery he believed was on schedule if not getting way ahead of it.

Though there were some early misgivings through the rocky summertime, taper did eventually happen by December. |

|

| Bernanke then left the job in February 2014 giving way to a cautiously optimistic Janet Yellen. For most Economists and those in the financial media, there was no need to be so careful; soon the “best jobs market in decades” therefore, everyone said, a far higher inflationary potential from an “overheating” domestic economy.

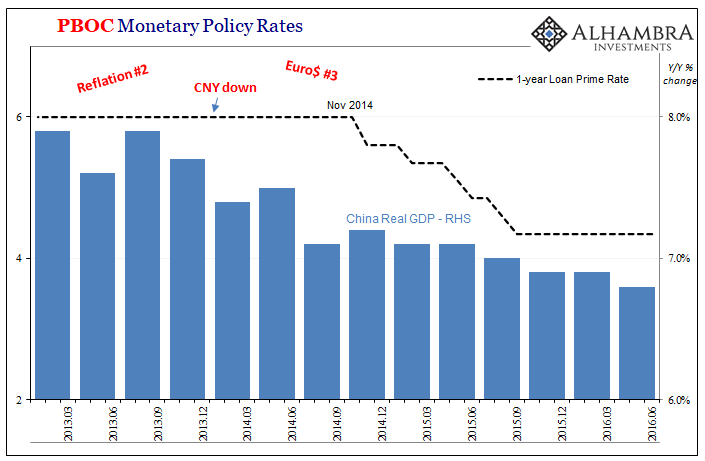

As 2014 drew toward a close, by November the Fed had already effectively terminated the two QE’s, leaving it to only reinvest maturities from then onward (until QT in 2017). Rate hikes in the US were expected to follow very soon thereafter. But that particular November wasn’t so one-sided as it may have seemed at the time. While monetary policy “hawks” were confidently gathered here, over on the opposite side of the Pacific the Chinese flipped to the entire opposite direction. On the 21st of that month, China’s central bank, the PBOC, cut its Loan Prime Rate (LPR) from 6.0% down to 5.6%. The LPR had been a reformed market-driven benchmark put together just the year before in October 2013 and has since been revamped in August 2019. Basically, China’s top commercial banks (now 18 on the panel) submit what they say is the best loan rate for their top customers at either a 1-year (the benchmark) or 5-year term. |

|

| Calculating the LPR begins with a monetary policy rate, the MLF, upon which the panel of banks add the lowest risk premium they would charge on top of it for these best bank borrowers; making the LPR a theoretically beneficial way for China’s central bankers to influence otherwise market prices for basic lending (it’s a bit more complicated than this, but for our purposes this is a useful if truncated description).

To begin 2014, the flattening US Treasury curve warned of the impending setback – either ignored, dismissed, or rationalized – alongside the change in direction for China’s currency, CNY. The LPR later in November merely the next escalation in a growing series of alarms flushing over the eurodollar system before then the entire global economy. More LPR cuts in China followed regularly in 2015, along with RRR cuts, and by 2016 when these did nothing to help arrest the economic and financial slide (recall August 2015’s immensely disruptive CNY crash), it was left for the Communist government to reluctantly dust off its Keynesian textbook in one last hurrah for the text as well as Li Keqiang using it. The November 2014 cut in the LPR, the first as the LPR (there was a pre-existing benchmark loan rate before), should have poured freezing buckets of frigid water all over the Western “overheating” narrative. On the one side over here, hawks; at the exact same time on over there, doves. This was always going to end up as an either/or situation. |

|

| History, and Janet Yellen’s confused 2015 stare, proved which way both sides would eventually fall. Rather than recovery as Bernanke had surmised in 2013, Euro$ #3 would end up wrecking it – globally – which in 2014 began to first and primarily cut into China’s (and emerging market) growth and forward prospects regardless of every PBOC action intending to counter this.

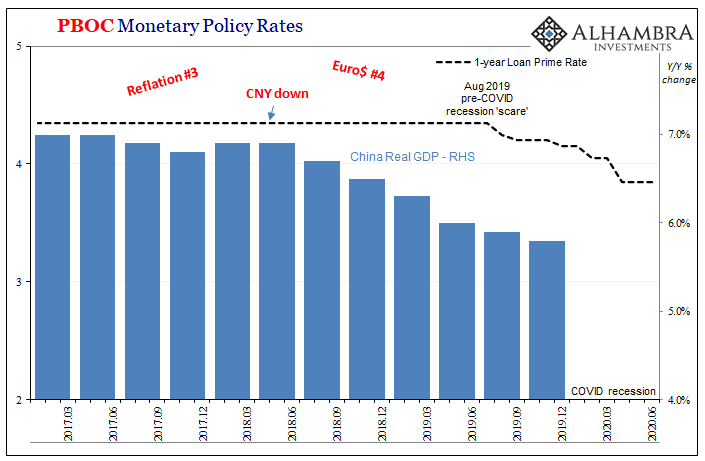

This leaves the LPR, like the RRR, not “stimulus” but rather a concrete sign of deterioration ongoing to a sufficient degree the normally patient and careful Chinese feel they can no longer afford to remain patient and careful. Moving forward in time to 2018 and 2019, in this next instance (Euro$ #4) Chinese authorities acted in that very fashion; holding off on moving the LPR (though cutting the RRR several times in 2018) until after its second reform in August of 2019. Unlike Euro$ #3, by then the PBOC’s shift to “dovishness” would align with Jay Powell’s confused 180-degree shift into that same direction – at practically the same time. As I started, here we are in 2022 all over again. Jay Powell’s in the process of terminating his QE6 with a schedule for hawkish rate hikes planned over the months ahead (joined this time by Europe’s ECB). |

|

| Yet, at the very same time, going back to last month, actually, the PBOC has also begun moving in the opposite direction as if it was November 2014.

And, for good measure, as we’ve been documenting over the same recent months the global bond market, the UST curve joined and amplified by inversion on the eurodollar futures curve, is also siding with the Chinese in practically the same way it had seven and eight years ago (and like three and four years ago). |

|

| Given these competing directions, has the Fed’s FOMC learned anything, or has something changed in the Chinese economic and financial superstructure to delink or decouple China from the rest of the world?

The answer to that question is the reason we continue highlighting these same things by thinking back in time to review all these eerily-same episodes which keep repeating one after another. China’s internal struggles aren’t really about China nor are they kept, as they don’t originate, internally. This is all bellwether stuff in China. Synchronized. I don’t much like quoting the guy, but you have to give Xi Jinping credit for understanding the way it all works in a way US policymakers seem unable – unwilling – to follow. |

|

While economic and inflation euphoria and certitude abounds unabated in this part of the world, around much of the rest of it the “growth scare” is in many ways already into “declines” and in serious danger of further “regressing.” That is the potential behind flattening curves, not inflation, even though those at the Fed have once again mounted its hawk. |

|

| This doesn’t mean the global economy falls off a cliff tomorrow, or necessarily at any point this year or next. What it suggests is, like 2014 or 2018, we’re pretty well assured to be heading in the wrong direction to some as-yet uncertain destination. Repeating the pattern, it’s just that American Economists, central bankers, and their media don’t realize the real dangers are visibly stacking up on the other side of the ledger from recovery, growth, and inflation. |

Tags: $CNY,Ben Bernanke,bond yields,Bonds,China,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,FOMC,Janet Yellen,jay powell,lending,Markets,newsletter,PBOC,QE,rate hikes,taper,Yield Curve