Economics is a pretty simple framework of understanding, at least in the small “e” sense. The big problem with Economics, capital “E”, is that the study is dedicated to other things beyond the economy. In the 21st century, it has become almost exclusive to those extraneous errands. It has morphed into a discipline dedicated to statistical regression of what relates to what, and the mathematical equations assigned to give those relationships some sort of meaning.

The immutable laws of economics care nothing of ferbus and the other DSGE models that try to make enough sense of a complex economy so as to fool policymakers into thinking they know both the precise as well as correct amount of some factor to achieve optimal results. There is so much wrong with that foolish idea it is often difficult to know where to begin.

We can start with the idea of optimal. Frankly, like equilibrium, there is no such thing. Even if there was, there surely wouldn’t always be one correct answer or quantification. The ideal of amount of something is only that based on perception, from whose perspective it is derived. Economists have allowed themselves to believe they are above it all, making such godlike decisions on the science of mathematics; they instead play out as the Three Stooges on the scientism of confused models that only embarrass them.

Basic economics teaches us that if something is in high demand, the price of that something will go up and often quite sharply. Again, no study or statistics is needed to establish this principle as the supply/demand curve is intuitively understood long before any student is misled by an orthodox textbook about what that “could” mean. This applies to all tradeable substances as well as effort, including labor.

Six and a half years ago, Washington State governor Christine Gregoire declared a state of emergency over apples. The state is, of course, famous for that particular produce, but the state of that emergency was unusual to say the least. There was no epidemic of some human introduced tropical disease threatening to destroy wide swaths of the industry, nor was there a weather emergency, an early season blizzard that you might typically associate with a mountainous region. I wrote about this more than four years ago and it sadly still applies:

Growers were expecting a massive haul of the crop but were unable to find enough labor to get it off the trees. With the first wisps of frost on the horizon, it would have been criminal to leave so much product to waste and spoil. And, ironically, that is exactly where the beleaguered applers turned.

Through her emergency declaration, the apple owners were able to procure criminal labor (or, more accurately, criminals as labor). Male “offenders” from the Olympic Corrections Center in Clallam County were put to work gathering in that massive harvest, earning all of $8.67 per hour. That, of course, was not the true cost rendered to the apple growers since the state had to pick up the tab (or at least part of it) for transportation and security. That amounts to a government subsidy of growers and perhaps even an expectation for future subsidies.

It was not economics but politics, with bastardizing economics in order to fit the politics. The correct economics, small “e” again, was instead:

Contrary to that assessment, the markets at the time were declaring that rotting apples were exactly what was needed. If there was genuine demand for all that ripening inventory of unharvested apples, it would have been reflected in the price paid by wholesalers and ultimately consumers. That would have afforded the apple growers the profit opportunity to increase the price paid to marginal labor.

In 2011, the most quoted and advertised price for labor was $22 per bin. They were even advertising wages as high as $120 to $150 per day. And yet the labor “shortage” persisted. If there truly was a market demand for all those apples, the prices would have converged to the point that both labor and business would have been satisfied.

If we say there is a labor shortage we must, apparently, more precisely define the term. In almost every case what it means is that there isn’t enough available labor at the price whatever business is advertising to pay. The shortage, then, isn’t really one, and in fact what it says is nothing more than wages are too low for that particular effort. Increase them enough and the labor shortage magically (for politicians and far too many “economists”) will disappear. And if the price of labor rises above your profit point, the market is telling you something else – go do something else with your capital.

The issue is not really apples nor the Pacific Northwest’s ability to satiate national and international demand. The general economy theme of 2015 was recovery after “transitory” weakness; the theme of 2016 was making sense of weakness that wasn’t “transitory” after all; for 2017 it has been drug addicts and lazy Americans to blame for all economic ills. Throw in a good dose of politics (to be perfectly clear, I am rendering no opinion on anything other than labor economics) and you get this from CNN:

He is Talib Alzamel, a 45-year-old Syrian refugee who arrived here last summer with his wife and five children. He can’t speak much English, but neither can most of the 40 refugees who work at Sterling Technologies, a plastic molding company based near the shores of Lake Erie. They earn $8-14 an hour.

The refugees at Sterling come from all over the world, from Syria to Sudan, Chad to Bhutan. And they’ve all passed the company’s standard drug test.

“In our lives, we don’t have drugs,” said Alzamel, who was hired within three months after arriving in Pennsylvania. “We don’t even know what they look like or how to use them.”

This article could have been written by the staff at the Federal Reserve Board. Its main diagnosis is that, “the percentage of American workers testing positive for illegal drugs has climbed steadily over the last three years to its highest level in a decade.” Because the US workforce is in some large proportion unemployable, it is increasingly claimed, we must import as much labor as possible because without them there is a harmful paucity of legitimate labor supply.

“In the Sunday newspaper there was a four- or five-page spread for employment advertisements and almost every one of them said, ‘Must pass a background check and a drug screen.’ So there’s a lot of people who are unemployed as a result,” said Amanda Milleren, a drug-addiction counselor at Cove Forge Behavioral Health System in Erie.

| With so many jobs being advertised and employers complaining constantly about being able to fill them it is assumed there must be undue scarcity. What’s missing from the whole discussion is wages, which is surprising (not really) because it happens to be the key to everything in the world of economics, as well as Economics. |

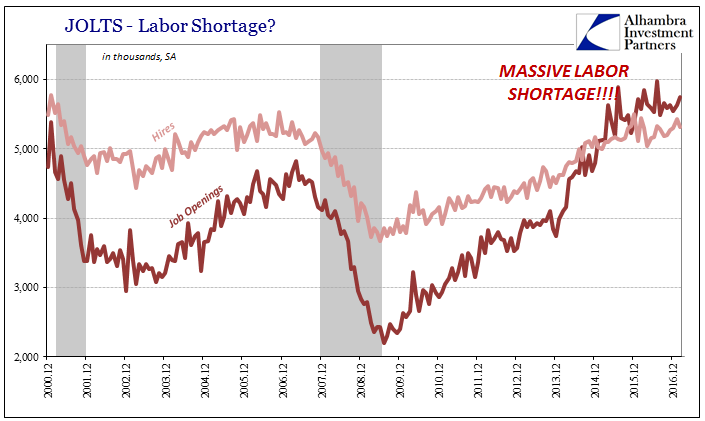

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey, Dec 2000 - 2016 |

| This idea of labor imbalance has been given the gloss of science based on a secondary labor market set of statistics, including one, Job Openings, that had only a few years earlier been the subject of much consternation and debate. Starting in January 2014 the estimated level of Job Openings surged while the rate of hiring did not, leaving several assumptions to have been paired with the anecdotes like those above to arrive at the opioid epidemic and the retirement of Baby Boomers. The timing of 2014 is just so alluring, for that was exactly when the US economy in particular was supposed to take off.

If the demand for labor was that strong in reality, there is no way it would escape small “e” economics, meaning wages. Employers in a truly booming environment would pay up for both skilled as well as unskilled labor in order to take advantage of opportunity – the opposite case for October 2011 and Washington apple growers. The difference between demand and supply in that arrangement would be witnessed in the concurrent surge of earned income rates. It had been this way time and again in history. |

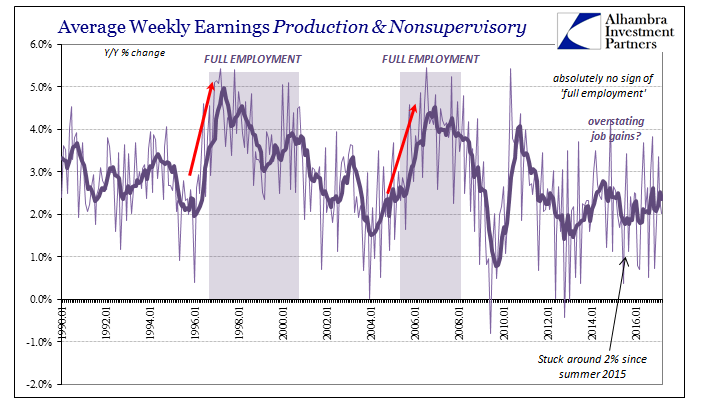

Payrolls and Average Weekly Earnings, Jan 1990 - 2017(see more posts on average weekly earnings, ) |

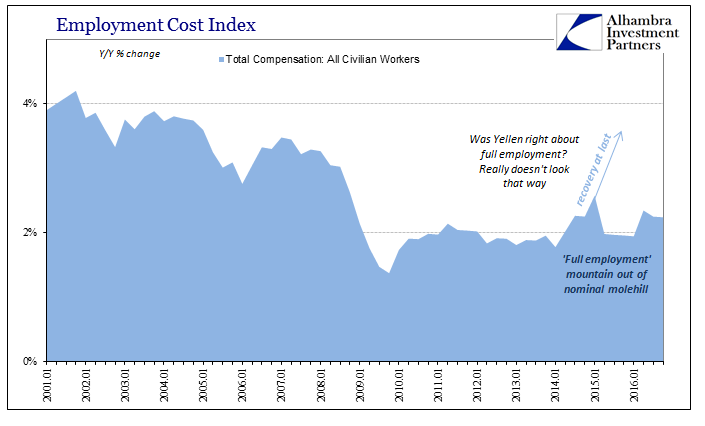

| That is, in fact, what Economists were expecting at the time. It was widely believed that every single upturn of regular monthly variation in whatever wage-related statistic (the Q1 2015 Employment Cost Index got Economists particularly excited for, as usual, no good reason) at whatever time heralded the start of wage inflation. As noted last month, Economists have been seeing nothing but signs of wage inflation for three straight years. After so long of divining from only cryptic gestures, it is pretty clear by now there just isn’t any wage inflation nor will there be. |

Employment Cost Index, Jan 2001 - 2017(see more posts on employment cost index, ) |

| If there isn’t wage acceleration, then how can there be a shortage? Earlier you may have already detected a big problem with the heroin excuse for economic (and Economic) failure. The statistic cited indicated that drug use rose over “the last three years to its highest level in a decade.” Was there a similar labor shortage ten years ago when “the percentage of Americans testing positive for legal drugs” was as it is now? Of course not, for you are only supposed to focus on “climbed steadily over the past three years.” |

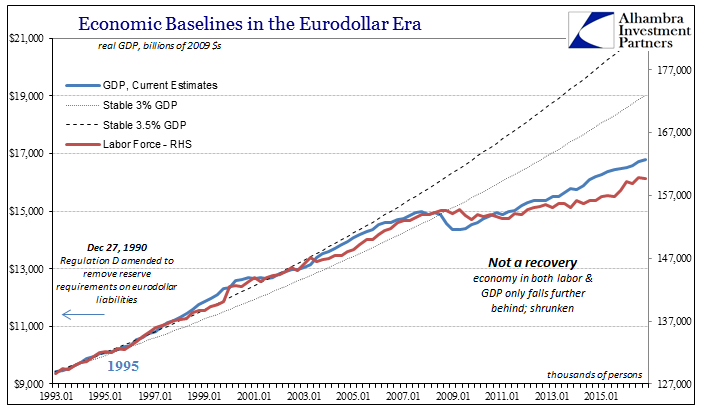

GDP Baseline Labor Force, Jan 1993 - 2016(see more posts on Gross Domestic Product, labor force, ) |

| There is a much simpler explanation for why the labor market may have dramatically changed in just this last decade that has nothing to do with drugs, retirement, laziness, or criminals picking apples. The economy shrunk in late 2008 and has never recovered because Economists took ten years just to figure out that it had shrunk and will probably take another ten at the very least to figure out why (if the world can last that long). It is especially true in the age of central banking since the solutions are right within the domain of central banks – money, not heroin. It answers not just wages but most especially why in 2014 (“rising dollar”) the global economy so thoroughly soured rather than soared. Basic economics. |

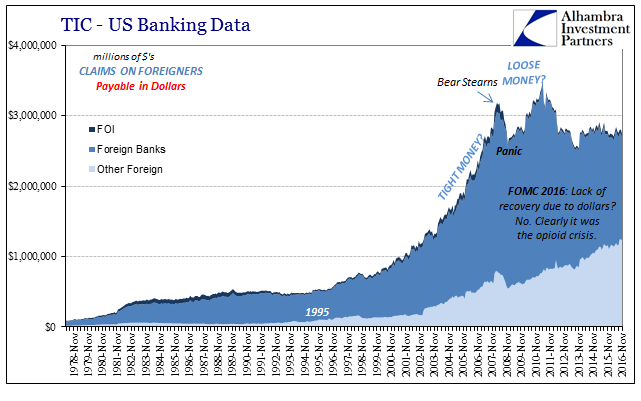

TIC - US Banking Data, Nov 1978 - 2016 |

Tags: Apple,average weekly earnings,Business Cycle,currencies,depression,earnings,economy,employment,employment cost index,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Gross Domestic Product,hires,Janet Yellen,job openings,jobs,jolts,Labor,labor force,Labor Market,Markets,Monetary Policy,newslettersent,Output Gap,recovery,retirement income,slack,unemployment rate,wages