The new covid variant and quick imposition of travel restrictions on several countries in southern Africa have injected a new dynamic into the mix. It may take the better part of the next couple of weeks for scientists to get a handle on what the new mutation means and the efficacy of the current vaccination and pill regime.

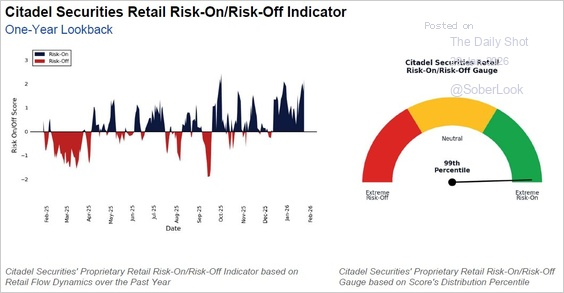

The initial net impact has been to reduce risk, as seen in the sharp sell-off of stocks. Emerging market currencies extended their losses. The JP Morgan Emerging Market Currency Index has fallen in eight of the nine sessions. Among the major currencies, the currencies used to fund the purchase of other financial assets, namely the yen, Swiss franc, and euro, strengthened in response to the covid news. The currencies that are seen levered to growth, like the dollar bloc and Scandis, fell.

Although it may not always seem that way, there are few sure things. We occupy a probability world. What is known and not known about the new variant leads market participants to reduce the odds that the old trajectory would continue unabated. In the context of the sensitivity of foreign exchange prices to monetary policy, that trajectory was characterized by an elevated risk of a BOE hike next month and for Fed to accelerate the pace of tapering. The sharp rally in the fed funds and Eurodollar near-term futures contracts reflect the market reassessing the odds. The implied yield of the December 2021 short-sterling interest rate futures contract fell to its lowest level since September 23.

The week ahead features the US November jobs report and the eurozone's preliminary estimate of November CP, which are the stuff that moves markets typically. Yet, the new variant may overshadow the economic data.

Before the emergence of the new variant, the rising infections in Europe seemed to be having a minimal economic impact. The flash composite eurozone PMI rose in November, the first increase in four months, and at 55.8 suggest output remains robust even if not as much as in Q3 (average composite PMI was 58.5) and Q2 (average composite PMI was 56.8). Moreover, the eurozone Sentix expectation survey for November rose for the first time in May. Indeed, it fell more in July and August than it did in September and October.

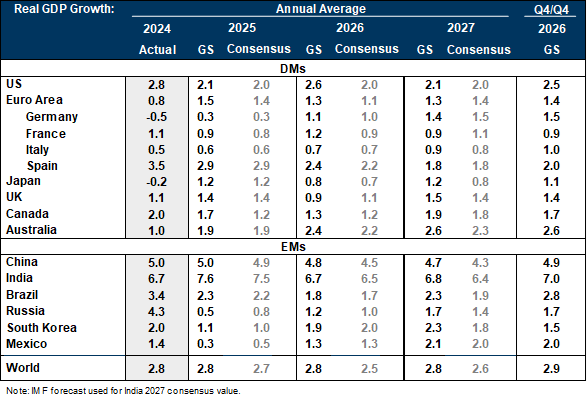

That said, economists have been anticipating a sharp slowdown in EMU growth in Q4. Recall that after contracting in Q4 20 and Q1 21, the eurozone economy expanded by 2.1% in Q2 and 2.2% in Q3 (quarter-over-quarter). The median forecast in Bloomberg's survey sees 0.8% quarterly expansion through the first half of next year. It is bound to be more volatile than that, and the risks are on the downside in Q4 21 and into Q1 22.

On the other hand, the US economy is accelerating after the disappointing 2% annualized pace in Q3. Nearly all of the high-frequency monthly data was stronger than the median (Bloomberg) forecast in October. Rising consumption is a critical factor. Consumer durable purchases are important, and next week's news is expected to include the second consecutive increase in auto sales after a collapse from April (18.5 mln vehicles seasonally adjusted annual rate) through September (12.18 mln).

Two main forces drive US consumption. First, the wealth effect is captured in rising financial assets and house prices. It is arguably what has let many people retire early since the pandemic struck. Then there is the income effect. Government transfer payments are essential even in "normal" times. While some programs, like the federal supplemental unemployment compensation, have expired, others, such as the enhanced child-earned tax credit, have only recently begun. Still, wages and salaries are key, which brings us to the November jobs report on December 3.

From a high level, the US labor market is sizzling. It filled an average of 582k jobs a month through October. Economists look around another 500k people to have joined the payrolls in November. The ADP private-sector jobs estimate has been lower than the national estimate by an average of 23k a month over the past three months and about 51k a month so far this year. The median forecast in Bloomberg's survey projects that about 525k private sector jobs were filled in November. Manufacturing employment, which surged by 60k in October, the most since last June, is expected to have slowed to 45k, which is still about 50% higher than this year's average pace.

Unemployment is expected to fall to 4.4% from 4.6%. Recall that it was above 6% until May. The underemployment rate is also falling. While much of the labor market has evolved as Fed officials, investors, and households had hoped, a problem remains. The (relatively) low participation rate remains problematic. Before the tech bubble burst in 2000, it hovered around 67% and was bouncing around 66% when the Great Finance Crisis hit. It fell to about 62.5%, and 2014-2019 appears capped approximately 63%, though, in late 2019, it reached an eight-year peak of 63.4%. Covid saw the rate plummet to 60.2%. It has recovered, but it has been 61.6%-61 since April.7%, first seen in August 2020.

Outside of regulatory issues and where climate change and monetary policy intersect, this is one of the few issues that seem to separate Powell and Brainard. Given the trade-offs, theFed Chair seems open-minded about it but is unsure that the previous participation rate can be achieved. Dr. Brainard also seems open-minded but tilts in the other direction. This appears to be one of the few issues that former Treasury Secretary Summers agrees with Bernanke.

The eurozone is in a difficult position. While the preliminary composite PMI ticked up to rise for the first time since July, the news has been overshadowed by the rising pandemic in Europe. Some new social restrictions have been implemented, spurring large-scale protests in some countries. It may take a little while for the impact to be seen in the real sector data. However, sentiment indicators may detect it first. The November German IFO assessment of the overall business climate, reported last week, fell to its lowest level since April. It had been pulling back since recording the cyclical peak in June.

At the same time, price pressures are accelerating. Higher energy prices, a weaker euro, and the base effect point to the risk of a large rise when the preliminary estimate of this month's aggregate CPI is reported on November 30. The statement that accompanied the preliminary November PMI noted that the selling price in the manufacturing and service sectors accelerated to almost 20-year highs. Brent crude oil is off slightly this month, but natural gas prices have soared by more than 40% since the end of October.

The euro was having a poor month, falling more than 3% against the US dollar to levels not seen since July 2020. It pared some of these losses ahead of the weekend, leaving it off about 2.3%. And to aggravate the situation, recall that EMU CPI fell by 0.3% in November 2020. When this drops out of the 12-month comparison, the chances of a shockingly strong number rises. The median forecast in Bloomberg's survey for CPI to rise to 4.3% from 4.1% seems too cautious. The report will provide fodder for the debate at the December 16 ECB meeting.

The meeting is expected to confirm that the Pandemic Emergency Purchase Program will end in March as currently planned. The "modalities" of the Asset Purchase Program will also be announced. The size, flexibility, and duration are of prime interest. The hawks may crow about the high inflation. Still, the ECB's leadership appears to have majority support that the price pressures are temporary and mostly related to the distortions around the pandemic. While a surge in CPI could embolden the hawks, the virus wave works against looking past the emergency too early.

Three other events will draw attention in the week ahead. The first is China's November PMI. We don't think the details matter so much. It is manufacturing PMI has fallen without interruptions since March and has been below the 50 boom/bust level in September and October. The non-manufacturing PMI recovered from the drop below 50 in August (47.5) but slipped in October and is expected to have fallen in November. The composite has been trending lower this year. It peaked last November at 557. and stood at 50.8 in October. Officials are dissatisfied with the growth and the risks to the economy. Beijing is encouraging lending, including to the property market, and wants local governments to step up their spending. Word cues by the PBOC have renewed speculation about a cut in reserve requirements (the last reduction was in July).

Second, on November 30, Treasury Secretary and Federal Reserve Chair Powell testify before the Senate Banking Committee on the CARES Act, the first (of several) fiscal responses to the pandemic. It was a $2.2 trillion effort approved in March 2020. The Federal Reserve welcomed the initiative, and Powell has often recognized the importance of fiscal support. To the extent that either official talks about the current economic conditions, investors will take notice.

Third, OPEC+ meets next week to set policy. It had been set to boost output by another 400k barrel per day in December, but several countries announced intentions to sell some of their oil reserves, which may change their calculus. It looks like the consumer nations may release 65-70 mln barrels. It was led by a 50 mln barrel commitment by the US, which includes accelerating the sale of 18 mln barrels that it had previously planned, which was related not to an emergency but a previous budget deal.

The remaining 32 mln barrels are not entirely sold, more like lent out and would be returned. It could take several months for the operation to be completed. Reports indicated that China would provide more oil, but it seemed to cast doubt on a coordinated effort. The UK offered 1.5 mln barrels of oil but conditioned it on the willingness of the private sector to participate.

The oil that the US is making available is the heavy sour crude that needs more refining and is not desired by US refiners. A gasoline shortage remains. Reports suggest India and China refiners have been the beneficiaries of the sales of US crude this year. Paradoxically, the US wants to deter Chinese companies with military ties while selling it oil used to fuel tanks, ships, and planes. Lenin's quip about capitalists selling the rope that will be used to hang them comes to mind, despite the Trump tariffs remaining in place.

OPEC+ may want to send a signal that it will avoid another devastating price war. Investing in crude capacity and carbon, more generally, is not in vogue. Ironically, the risk is that the reluctance to invest in the old economy may deter the transition to the new economy. Several OPEC+ members do not have the capacity to boost output and therefore have been falling shy of their 400k barrels a day increases, but the members who have the capacity have not made up for it. January WTI peaked a month ago near $83.85. Before the weekend, amid the volatility unleashed by the new variant, it tumbled to $67.40, a 13% decline and more than a three-sigma move. It is slightly above the 200-day moving average, which it has not traded below this year.

Tags: China,COVID,ECB,Featured,federal-reserve,inflation,jobs,Monetary Policy,newsletter,OIL