Defying ExpectationsWhy is the stock market seemingly so utterly oblivious to the potential dangers and in some respects quite obvious fundamental problems the global economy faces? Why in particular does this happen at a time when valuations are already extremely stretched? Questions along these lines are raised increasingly often by our correspondents lately. One could be smug about it and say “it’s all technical”, but there is more to it than that. It may not be rocket science, but there are a few issues that are probably not getting the attention they deserve. |

|

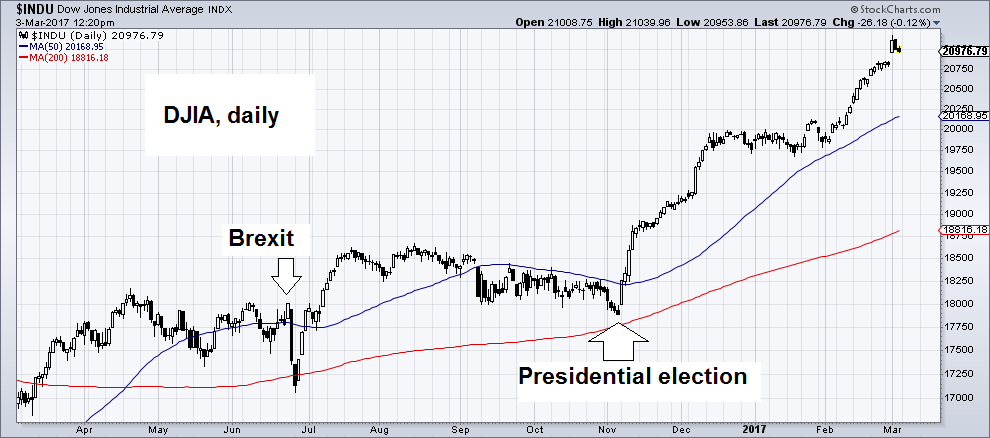

| As you can see below, we have marked “Brexit day” on the chart as well, which was another noteworthy juncture. Not only was the success of the “Leave” campaign just as big a surprise as Trump’s election victory, but it was yet another occasion on which the market ended up fooling most observers by dramatically reversing course after a mere two days of relatively mild panic selling.

Not to belabor the obvious too much, but it is actually a hallmark of bull markets that they ignore any and all bad news. In fact, bad news quite often end up extending the lives of bull markets, not least because they help with sustaining a certain degree of skepticism among market participants. To be sure, at times that is not the only reason. In the “Brexit” case we have little doubt that the reaction of central banks to the outcome of the referendum played a big role in the market reversal. We have discussed the market’s post-election performance before, but here is a reminder of how deeply ingrained the views about the likely effects of a Trump victory on the stock market were. As the probabilities shifted toward Trump winning on election night, DJIA futures intermittently fell by more than 900 points in Asian trade. Many Trump opponents felt compelled to remark on this without awaiting further developments. Paul Krugman for instance made an especially ambitious forecast that was shredded within a few hours:

Admittedly we like poking fun at Paul Krugman. That is however not the point here, the opportunity to pick on Krugman is merely an agreeable side effect. The point is that his comment is an excellent illustration of the expectations prevailing at the time. Our own forecast was by no means better – we did map out possible near term paths for the market depending on the election outcome, but none of these assigned a very high probability to a blow-off rally, even if the possibility was at the back of our mind some time ago already. We have previously stated that we believe the overnight reassessment of the market’s prospects after the election was inter alia motivated by the Republican party’s “clean sweep”, i.e., the fact that in addition to its candidate becoming president, it managed to win majorities in the House and Senate as well. That made it more likely that Trump would be able to enact his economic policies and wouldn’t have to face a hostile Congress. That was likely the immediate trigger, but not the main driver of what has happened since then. |

DJIA Daily, March 2016 - 2017 DJIA, daily. Since the US presidential election, the stock market has rallied relentlessly, after breaking through a long-standing resistance level with ease. The move since then is increasingly looks like a blow-off rally, and we think that is precisely what it is – click to enlarge. - Click to enlarge |

The Fundamental Driver of the Blow-Off Rally in StocksStock prices have been driven to valuations that seemingly make little sense from a fundamental perspective. We believe the main culprit was way above-average money supply growth over the past eight years. What we are seeing now are partly its lagged effects; its pace actually remains quite brisk, but it has begun to slow down noticeably and that seems set to continue. The recent market action displays a number of characteristics typically associated with a final rally phase. What we say about the stock market below is premised on certain basic assumptions – the most important ones are the following:

|

Hussman Strategic Advisors, 1950 - 2016 |

The expected nominal 12-year return of the S&P 500 index based on gross value added, via John Hussman (the concept is explained here). The current outlook is the worst since the peak of the tech mania. The indicator has been back-tested to 1950, i.e., essentially the bulk of the post WW2 era and has worked quite well so far.

The first assumption depends directly on the second, which we admit may turn out to be incorrect at some point in the future. A number of scenarios is imaginable in which it would have to be reassessed, but these seem unlikely to be relevant in the near to medium term. That may change in a severe enough “economic emergency” situation. We mention this for the simple reason that everything we state below is simply not applicable to nominal stock prices in a hyperinflation environment. |

IBC General Index in Caracas, 2000 - 2017 The IBC General Index in Caracas. This index was at 6 points in early 2002 – it is at 37,600 points today. After a recent correction, it has rallied from 27,500 points to 37,600 points in a mere two months. This illustrates that inflation is a far more important driver of stock prices than other inputs. In hyperinflation any considerations about earnings and valuations become utterly meaningless – stocks will rally even if the companies listed on the exchange operate in an economy in total free-fall. The chart of the IBC General is simply a reflection of the collapsing value of Venezuela’s currency. - Click to enlarge |

| The same things that are happening at the moment could be observed in the late stages of the 2003-2007 mini echo bubble and the bubble of the 1990s that preceded it: just as the time arrived when money supply growth and the trend in interest rates showed signs of beginning to deteriorate, a blow-off move got underway (incidentally this also happened in the late 1920s).

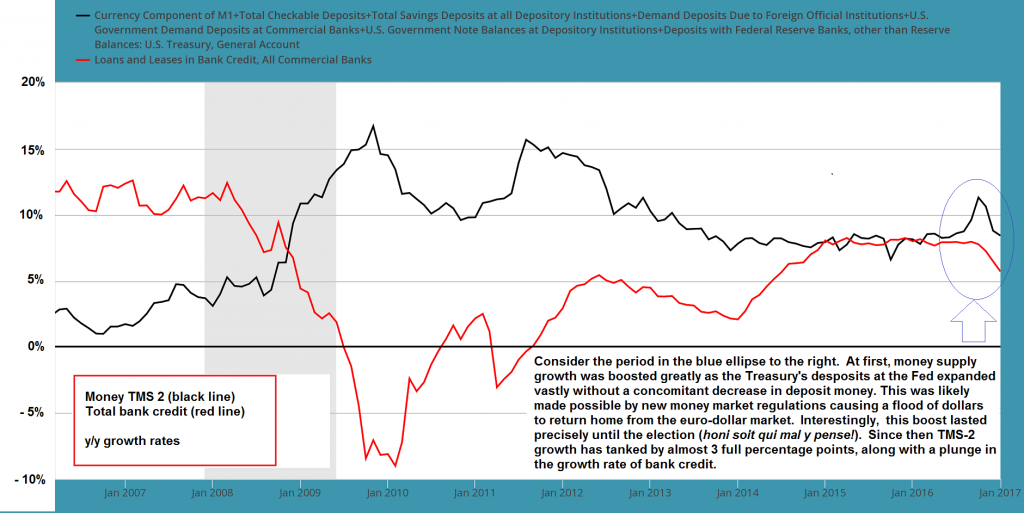

Two major phenomena always seem to coincide in these final blow-offs: for oon thing, the lagged effects of the preceding money supply expansion continue to play out. There is for instance a feedback loop between rising asset prices and the amount of money one can borrow using these assets as margin collateral. In short, there is inter alia a self-feeding spiral that is helping to push prices up further. Rising demand for credit to purchase securities is also contributing to upward pressure on market interest rates though, which the Fed is not actively countering at the moment. In order for the amount of money sloshing about in the financial sphere to become too small to support further price increases, money supply growth needs to fall below an unknowable threshold, that is a moving target to boot (even if we knew where it is at present, it would shift as time passes). When and whether this happens is determined by real economic activity, the willingness of banks to extend additional loans to the private sector and monetary policy. Note that the borrowing of companies for the purpose of buying back their own stock puts upward pressure on market interest rates as well, ceteris paribus. Over time it should also make banks more reluctant to lend, as they will become worried about the growing risks (even if CEOs ignore them). New money tends to spread across the economy in a wave-like movement. In the era of QE, it clearly enters financial markets first, but over time, some of it still “leaks out” from there. Low demand for funding in the real economy in an economy that is merely muddling along, perversely supports asset prices, as a smaller amount of money will be allocated to other uses than buying securities and the above mentioned “leakage” will be minimized. As long as enough money remains in the financial sphere to push stock prices higher in theory, they can also be pushed higher in practice. |

YoY Growth of TMS-2 and Total Bank Credit, January 2007 - 2017 Year-on-year growth of TMS-2 (broad true US money supply) and total bank credit. This chart illustrates several things: when the Fed became serious about increasing the pace of monetary pumping in late 2008, money supply growth took off like a scalded cat. Even though it is well below previous peak levels, the growth rate never went much below 7.5% y/y and cumulative growth from the end of January 2008 to the end of January 2017 was 141%, i.e., there is now almost 2 ½ times more money in the US economy than at the beginning of 2008 (you may have noticed that we have somehow failed to become 2 ½ times richer). However, the Fed is no longer expanding its balance sheet – QE has been reduced to replacing maturing debt held by the Fed – and the effect of money market regulations was a one-off event. Hence, money supply growth depends entirely on commercial bank credit expansion at present – and bank credit growth has begun to slow sharply. - Click to enlarge |

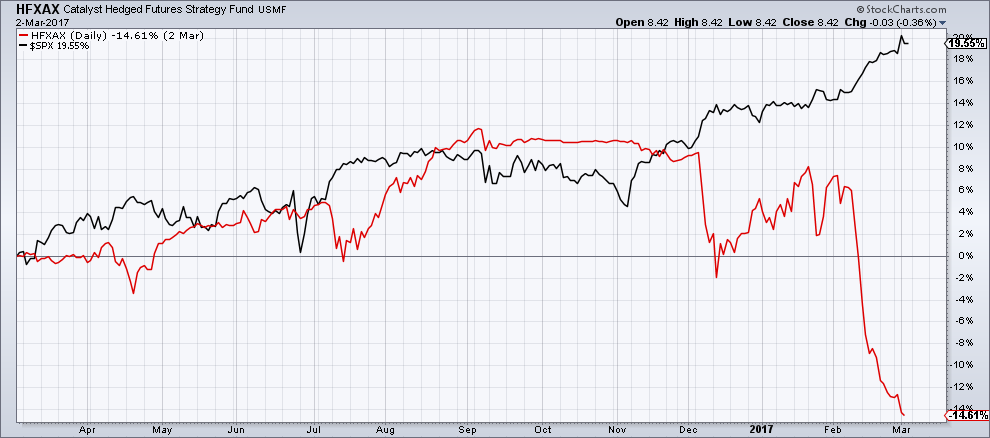

Market PsychologyThe second major characteristic of blow-offs are their underlying psychological drivers. By the time money supply growth actually begins to falter, bull markets are usually quite extended and stocks have been at elevated valuations for quite some time already. Many market participants who took profits and raised cash at an earlier juncture, or didn’t fully take part in the most recent rally phase because they could not bring themselves to buy at these valuations, are in a quandary at this stage. The market just keeps going up in spite of what their rational assessment told them to expect and they are increasingly under pressure as a result. Some investors employing call-writing or hedging strategies either blow up or are abandoning hedges because they are no longer deemed worth the cost (just as they actually become very inexpensive). Professional investors are particularly affected by this, as the short term underperformance that necessarily results from hedging and/or holding large cash positions begins to cost them customers. Here are two recent examples illustrating that we have arrived at such a juncture: Zerohedge recently reported that an open-ended hedged futures strategy fund (HFXAX) was forced out of a large number of S&P 500 call spreads involving a staggering amount of notional value:

The fund’s call-writing strategy has not fared well, to put it mildly: |

Catalyst Hedged Futs, March 2016 - 2017 HFXAX (red line) vs. SPX (black line), performance comparison. Note: there are two sister strategies, HFXIX and HFXCX. The former performed slightly better, while the latter generated an even bigger loss, plunging by 31.5% between late October and late February. Each of the three funds holds slightly more than $4 bn. in assets; that translates into a great deal more notional exposure in futures and options – click to enlarge. - Click to enlarge |

Our friends at INK in Canada recently pointed out to us that Canadian insurer Fairfax Financial recently took a US $2.66 billion loss on closing out its short position – here is a blurb from its annual report explaining the decision:

Quite a few investors have thrown caution to the wind long ago, but the blow-off stage is putting enormous pressure on those who were hitherto cautious or skeptical. Short sellers are only a small group and a highly sophisticated one at that, but at least some of them are likely forced to cover their positions as well. Retail investors were scared to get back into the market while memories of the last crash were still fresh, but they are finally losing their inhibitions too – the waters are evidently deemed safe again. This is evidenced by a dramatic reversal in fund flows and ETF inflows (e.g. $8.2 billion flowed into SPY alone on a single day last week) and the stunning collapse in Rydex money market fund assets. |

Rydex Data, 2001 - 2017 The top panel shows the collapse in Rydex money market assets – note that this is well aligned with the no less astonishing decline in the ratio between total stock market capitalization and all retail money market funds combined. Rydex assets an fund flows represent only a very small slice of total market activity, but are nevertheless generally a very good indicator of the mood of retail investors and small traders and we believe of investor psychology in general. - Click to enlarge |

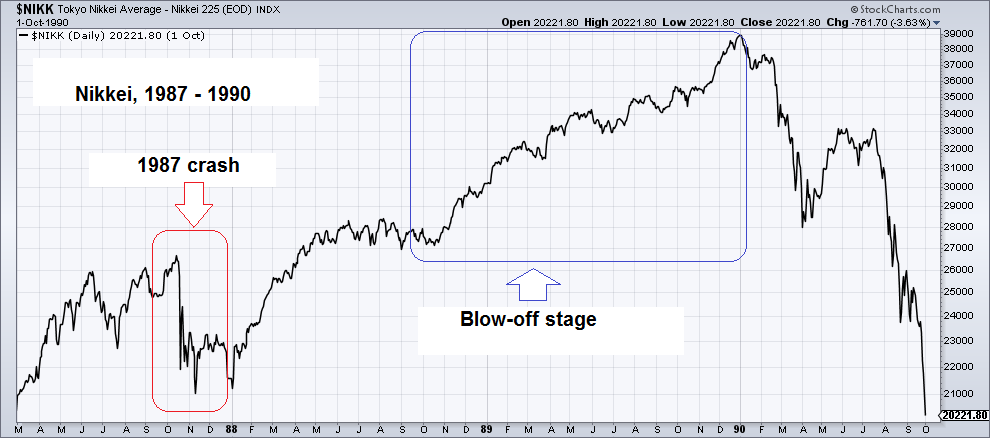

The StoryThe late stage of a stock market bubble is always accompanied by a “story”. For example, in 1999/2000 it was that “demand for technology will grow at X% (insert impressively high number) forever and ever”. Large productivity growth rates were similarly extrapolated and used to rationalize absurd valuations (incidentally the sharp slowdown in productivity growth in recent years is not mentioned very often). Once the final blow-off stage was underway, this underlying premise was decorated with amusing little side stories, such as e.g. rumors of a “DRAM shortage” (we remember laughing out loud when this was excitedly discussed on TV) and similar unlikely notions; not to mention that traditional valuation parameters were replaced by somewhat silly ideas like “eyeball counts”. The situation is probably no less crazy today, it is merely somewhat less obvious. The most egregious insanity is on display in stocks of unlisted so-called unicorns (and derivatives on them) which trade in private markets. Up until recently, the main “story” serving to rationalize valuations was unrelenting central bank support (not a completely unreasonable idea). A new story is underlying the current blow-off phase though – namely that Donald Trump, who was once held to cause nothing but “uncertainty”, is going to produce so much economic growth that valuations can be safely ignored. Within a few weeks, he has been repackaged into a kind of supernatural warp drive entity which American voters have lashed to the stock market in their infinite wisdom. The stories and psychological underpinnings of the late 1990s/ early 2000 blow-off briefly summarized above are representative of every stock market blow-off in history – even if the rationalizations are always slightly different. For instance, in 1988-1989, we often heard that although Japanese stocks were trading at an insane average multiple of 80, they could not possibly decline due to Japan’s incestuous Keiretsu cross-shareholdings system and the “wall of money” besieging the stock market. As we recall, only very few observers occasionally mentioned that sharply rising interest rates and weakening money supply growth might endanger this happy situation. |

Nikkei 1987 - 1990 The Nikkei from 1987 to 1990. it was the only index that immediately streaked to new all time highs after the 1987 crash (it was also the index least affected by the crash). Once the blow-off phase was underway, Japanese stocks were widely deemed invulnerable. The rationalizations offered at the time are quite interesting in retrospect, especially as some of them were later used to explain the market’s decline! The relentless surge in stock prices in 1988-1989 was no longer supported by money supply growth and interest rate trends. - Click to enlarge |

Up Next:

In Part 2 we will discuss blow-off pattern recognition: how one can tell whether a blow-off stage is underway; the self-similarity of blow-off patterns throughout history; what to expect when the blow-off stage concludes.

Charts by: StockCharts, John Hussman, BigCharts, St. Louis Federal Reserve Research

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Chart Update,newslettersent,The Stock Market