Central bankers nearly everywhere have succumbed to recovery fever. This has been a common occurrence among their cohort ever since the earliest days of the crisis; the first one. Many of them, or their predecessors, since this standard of fantasyland has gone on for so long, had caught the malady as early as 2007 and 2008 when the world was only falling apart.

The disease is just that potent; delirium the chief symptom, especially among the virus’ central banker variant.

One need only review the ECB’s absurd performance beginning just weeks before Lehman in order to understand just how this sickness totally wrecks (already limited) official faculties.

| On July 3, 2008 (July 2008!), Europe’s central bank raised its benchmark interest rate.

With other monetary authorities around the world (read: Ben Bernanke’s Fed) believed to have done more than enough to stem the worst of the limited (in official view) deflationary possibilities of some unknown banking thing-y (something about subprime mortgages in the US), the real risk, according to the ECB, was inflation. Let me reiterate: this was July 2008. One contemporary Financial Times’ summation of this same policy shift was apt if for all the wrong reasons (none really contemplated too deeply by the mainstream media which, at the time, as always, merely parroted whatever view central bankers might have held no matter how unbelievably ridiculous):

One more time: this was July 2008. And it sounds really, really familiar, no? |

UST Yield Curve, 2017-2019 |

| Learning absolutely nothing, not content to so prominently embarrass itself only the one time, if you don’t remember the ECB did the same thing again; I’m really not making this up. In early 2011, mere three years later, the ECB flipped to “focus more on rising inflation risks” with not one but two rate hikes…before the dozens upon dozens of rotted eggs running all down policymakers’ gathered faces shook them awake from their case of recovery fever.

Another outburst of global deflation (Euro$ #2) – not inflation – was running rampant throughout the global system taking especial interest and destructive notice of Europe. I wrote five and a half years ago (for all the same reasons):

Here we are yet again. Thus, is anyone surprised by the latest strain of recovery fever having free reign to ravage central bank circles all over the world? The Reserve Bank of New Zealand just last week announced it will wind down its QE program four days from now. Last month, the Bank of Canada reported that it would reduce (for the second time) the pace of its LSAP stuff and probably raise interest rates much earlier than previously anticipated. Back in May, the Bank of England’s monetary policy committee voted to simultaneously taper the rate of its own asset purchase program while at the same time steadfastly refusing to call it that. What’s perhaps more interesting is that US monetary authorities after having previously displayed just how highly susceptible they have been to the recovery virus, instead, in 2021, so far, they appear to have built substantial resistance to its current strain. Not only is the official view on inflation very different (transitory), as noted previously Jay Powell has surprisingly displayed recently a modicum of monetary competence (RRP = Tbill shortage). |

UST Yield Curve, 2013-2016 |

| We’ll get to that later, for now the global pattern simply repeats as it does in parts.

Recovery fever rages while the scientific reality of real economics (small “e”) keeps coming out in the opposite condition. The official world, and the media which blindly follows it (repeatedly off a deflationary cliff), may be content about the state of things but, as noted several times of late, the warning signs only proliferate. |

UST Yield Curve, 2009-2012 |

| Among them, we’ve said the next big one would be a “collateral day” (such as May 29, 2018) which has in the past signaled a serious rupture in the collateral stream so devious and disorderly that its ultimate deflationary consequences immediately afterward may have been all but inevitable (proven by repeated landmines).

Was today that today? Well, no. Government bond yields did fall substantially, beginning in Germany where they were off by a fair number, and then much more in the US Treasury market (the 10-year CMT yield declined by nearly 10 bps on the day). But this wasn’t quite the “buying panic” (or “scramble for collateral”) like those of May 29, 2018, or May 6, 2010, and nowhere near the early morning disorderly rampage on October 15, 2014. This isn’t to say there isn’t detectible collateral strain here; there is. It just hasn’t – to this point – reached that same kind of proportion as those previous, to their degree where we’d have to say the deflationary, collateral scarcity problems have clearly pushed out into something much worse: collateral shortage. |

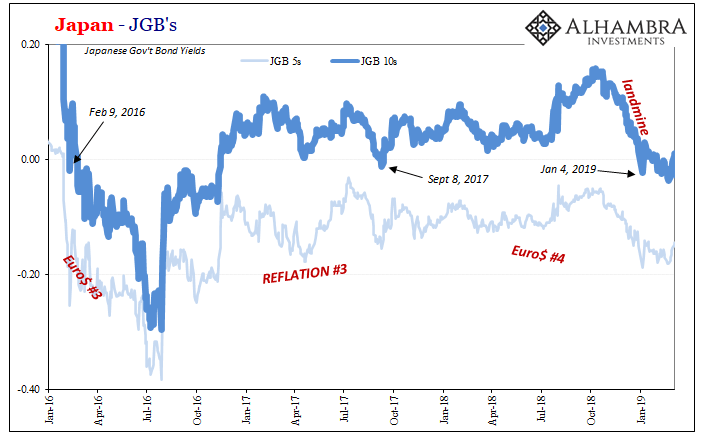

Japan - JGB's, 2016-2019 |

| In lieu of it yet making a 2021 appearance, let’s look around at another potentially serious fracture being ignored by those agitated with recovery fever: JGBs.

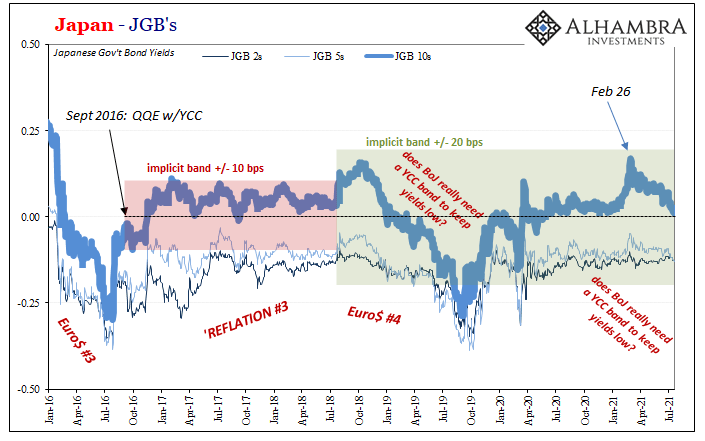

While German bunds were bid, and US Treasuries were very much sought after, JGB’s curiously didn’t move all that much (they might tonight, which is why this review). However, they have been moving for several weeks and are now tantalizing close to a significant threshold – the zero lower bound (ZLB). The ZLB might be a big deal for central bankers though it hasn’t been any problem whatsoever for Japanese government bonds. And that is the problem. What I mean is, crossing zero several times, this has been an important indication about the state of global factors (deflation or reflation) embedded within all global government bonds. In other words, whether dropping below zero or coming back up out from negative yields, when the JGB 10s cross the ZLB this has proved to be a noteworthy gesture either way. Right from the start, too, going back to when JGB 10s first dropped below the ZLB in early February 2016 – right as Euro$ #3 was becoming its most globally deflationary. But then when these 10s turned positive later in the year, they then managed to stay that way for more than two years consistent with Reflation #3. |

|

|

The lone exception was September 8, 2017, when the 10-year rate briefly hit -1.2 bps before turning positive again. But even on that day, with just the one day below zero, it was significant given what else happened in early September 2017 (a bunch of things beginning to point in the direction of what shortly thereafter became Euro$ #4).The next time JGB 10s went negative was early January 2019 following number four’s landmine. After temporarily going back positive, only flirting with zero from the positive side the rest of that month, by early February 2019 the yield was again subzero where it would remain until small, brief positives that December. |

Japan - JGB's, 2016-2021 |

| Thus, a flip – and even a brief one – from positive to negative for Japan’s 10-year government bond has proven to be a dependable signal (given wider context) that somethin’ ain’t right. For the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the folks at the Bank of Canada, and the taper-confused policymakers at the Bank of England, they might hope that this 10-year maturity in Japan’s bond market doesn’t go any further than it already has: |

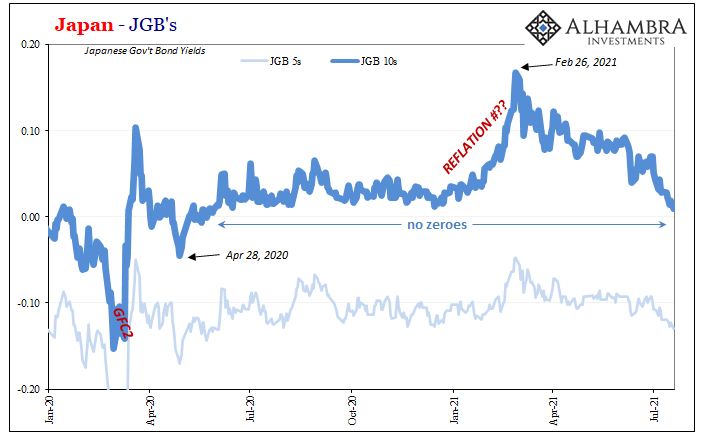

Japan - JGB's, 2020-2021 |

Trading right at zero intraday several times over the past week, these 10s haven’t yet closed at or below. But there’s no margin for further error left in them.

As you can see above, going back to late last April, like Reflation #3 the 10-year rate has been uniformly on the plus side of the ZLB; in fact, not a single minus along the way. A cross to the negative side, even if briefly, that would be an important development; even more so if it stays there (or, like 2019, rebounds positive only to come back minus in short order).

Any of those would be another key escalating warning of this building deflationary sense.

Not quite there yet, but, like the drop in yields today, another one coming really close.

And, history has conclusively shown, it matters nothing whatsoever just how serious these cases of recovery fever force delirious central bankers worldwide to taper or somehow other “hawkishly” adjust their policies. In point of fact, whenever central bankers display their singular sickness this has itself historically offered a sort of warning sign all its own. Just not the one they ever expect.

Media: How can we further prove we have no idea what’s going on?

‘Stumped’ Wall St: Uh, we’re the ones buying all these bonds. https://t.co/V6715eiqf3 pic.twitter.com/OuxBeiAsIG

— Jeffrey P. Snider (@JeffSnider_AIP) July 19, 2021

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,currencies,Deflation,ECB,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,german bunds,inflation,Japan,JGB,Markets,newsletter,rate hikes,Reflation,U.S. Treasuries