Abstract

In the following article we will explain which types of crisis occur in the euro area and will argue that this crisis will last at least another fifteen years.

(1) Competitiveness crisis: Before the euro introduction peripheral countries regularly saw their currency depreciate against the German Mark and helped them to increase their competitiveness. This is no longer possible with the euro. In addition, salaries and labour costs have increased strongly in many peripheral countries since the euro introduction, but retreated in Germany. Both together create an enormous gap between the German competitiveness and the ones of the periphery.

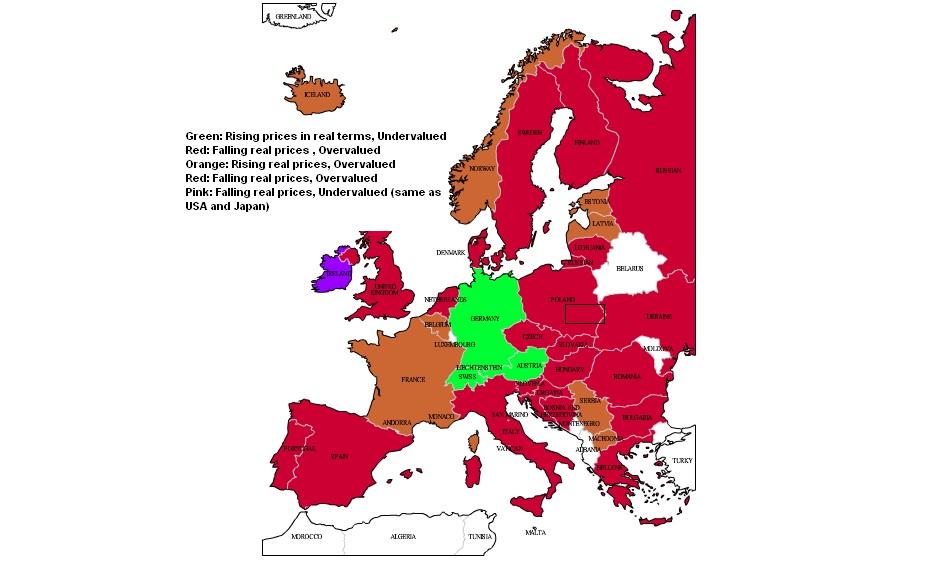

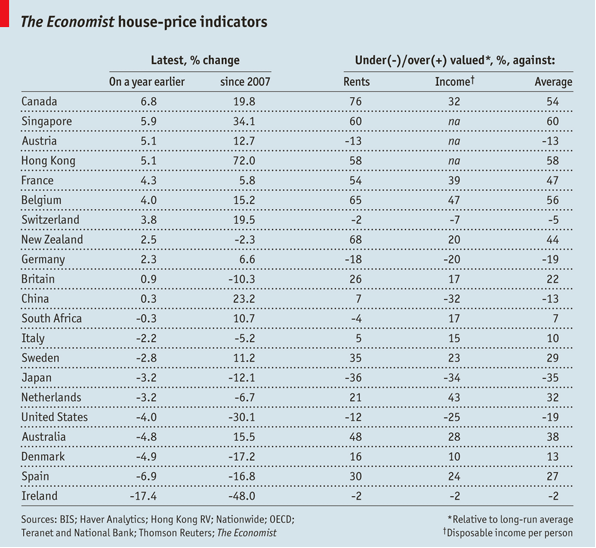

(2) Real estate crisis:Over-investment into real estate in stressed countries like Spain, Portugal, Cyprus and Ireland, but also in Denmark has happened between 2001 and 2008: House prices in these countries now fall and private households have difficulties in returning the debt. Several countries like France, Belgium and the Netherlands see extremely overvalued property prices, they are on edge on collapsing similarly.

(4) Structural defects crisis: Most countries of the euro zone possess a high public-sector share of the economy, a big welfare state and high social contributions to the labour costs.

(5) Demographical crisis: Most European countries see their population shrink, the ratio between working population and retired people is increasing.

(6) Sovereign Debt crisis: Yields for the “PIIGS” countries (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece, Spain) go up to levels at which the countries are considered to have difficulties in paying the debt back. This is caused by the real estate crisis in the case of Spain, Portugal,Cyprus and Ireland, low growth and already existing high debt levels (for Italy, Portugal and Greece). Cyprus and Slovenia have recently added to this list, Belgium is sometimes added because of its high debt levels.

(7) Banking crisis (sovereign debt part): Apart from saver’s money and owner’s equity the biggest part of the bank assets is sovereign debt. Leveraging on these two sources banks can expand their balance sheets (key word minimum reserve requirements). If, however the assets lose values with sovereign debt crisis, banks are constrained to reduce their balance sheets in a de-leveraging process (a credit crunch) or increase their equity. Again banks have difficulties in lending because they do not exactly how much sovereign debt the other bank actually has.

(8) Balance of payment crisis: German, Dutch and Finish private companies and their central banks accumulated more and more foreign assets in the other countries of the euro zone. The banks of these 3 countries were very active between 2001 and 2009, but since 2011 they are replaced are more and more their central banks (key word Target 2).

(9) Not optimum currency area: Originally the Maastricht convergence criteria wanted that the member countries of the euro have at most 60% debt, 3% deficit per year and a limited inflation of 2%. Especially the debt criterion had not been respected by many member states, whereas the deficit target had been fulfilled by some countries only by introducing special taxes. After the euro introduction Spain, Ireland, Cyprus, Greece had a 8-year boom thanks by cheaper money provided by foreign banks that did not see big differences in creditworthiness among the euro zone sovereigns. Germany, however, saw low growth. Thanks to an increasing German competitiveness the growth difference between the booming nations did not become too big during these years. From the financial crisis onwards the positions inverted: The northern countries have good growth, whereas the southern ones lack. Because of the other types of crisis two completely different zones have been created, a fact which completely contradicts the Maastricht criteria.

UBS has warned against a break-up of the Euro zone. We think that the Euro zone will effectively not break up, but the northern states will force the PIIGS to some necessary reforms. If these reforms are not done in time, what is highly probable, none of the PIIGs will be able to recover on their own, but they will all need to default on their debt in a similar manner as Greece recently did. Ireland may be the only the exception to this rule. With the time even a default of Italy or Spain will be possible without a break-up of the Euro zone.

The Gross National Products (GDP) is defined by GDP = C + G + I + (Ex – Im)

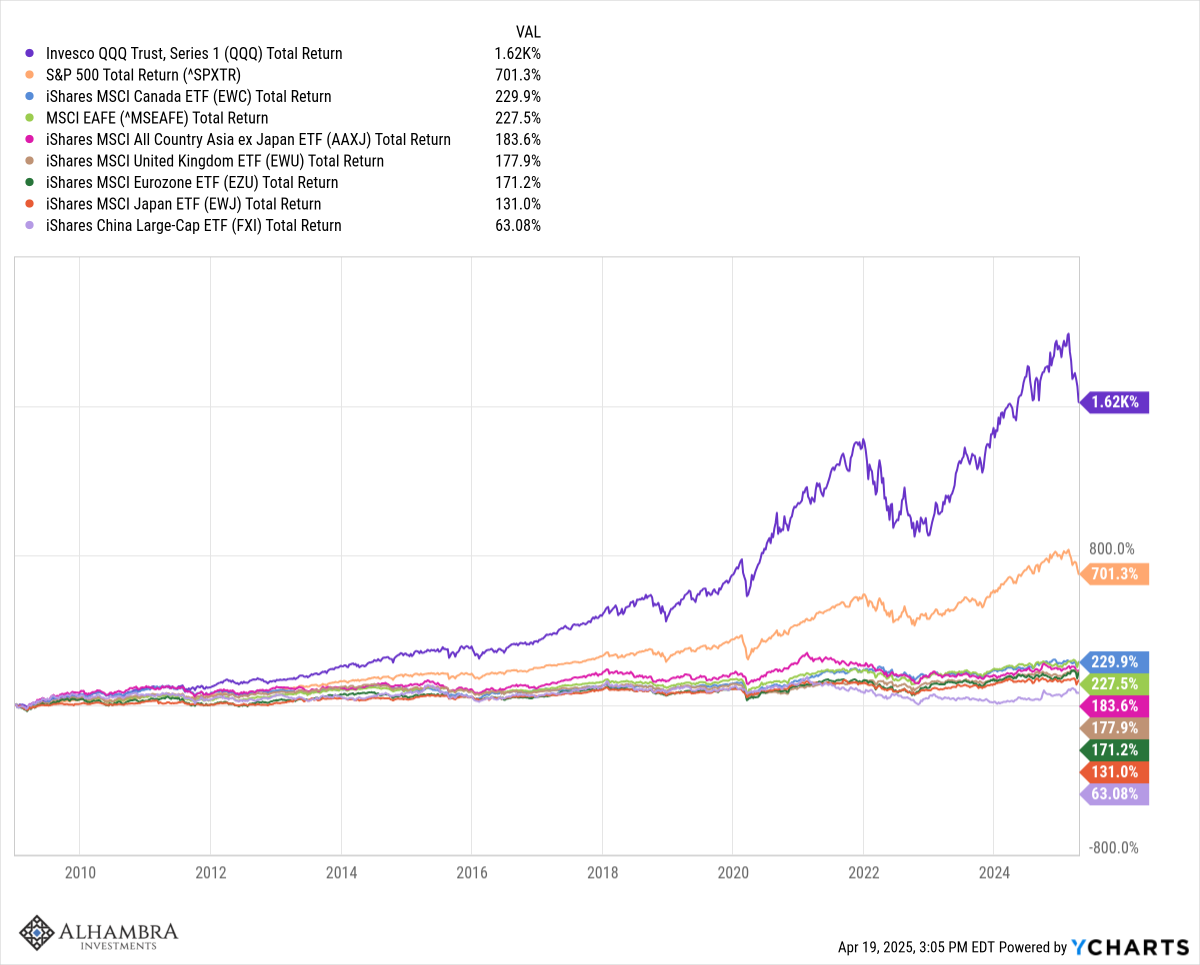

Along with the explanation of the types of crises, we will examine the components of the GDP. For each we will find out if, when and under which preconditions the peripheral countries of the Euro zone are able to generate growth. The Euro can only be resolved if the PIIGS countries are able to generate growth comparable to Germany. Only in this case they will overcome their financing problems.

Part A: Generating growth via export surpluses

(1) The competitiveness crisis

The typical way indebted countries can grow out of the debt is a positive trade balance and current account surplus.

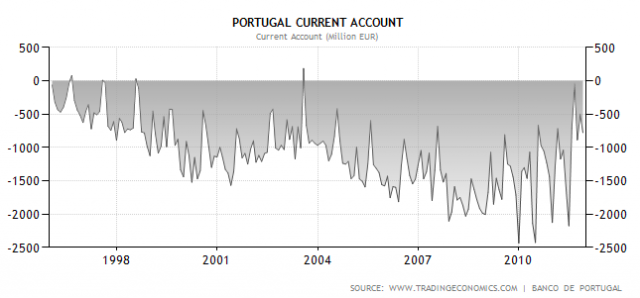

(1.1.) Growing imbalances in the European trade

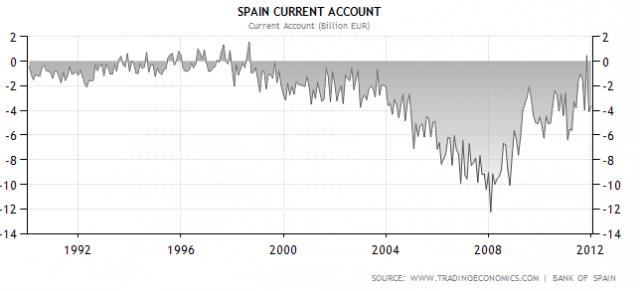

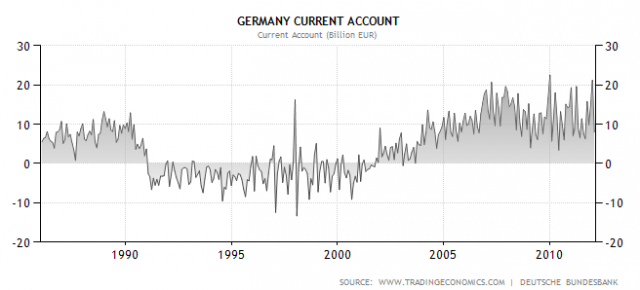

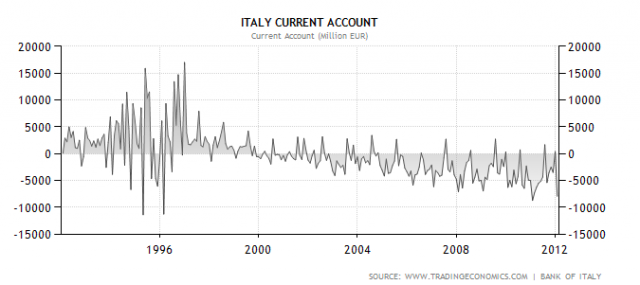

The trade balances of the EU countries in 2011 show that Spain (-47 bn Euro), Italy (-25 bn), Greece (- 21 bn) and Portugal (-15 bn) have significant deficits compared to Germany (+147 bn Euro). Spain, Portugal, Greece and in part Italy have not managed to obtain a positive current account balance in the last 20 years. The current account is a broader measurement which includes trade of goods and services (e.g. holidays in Germans in Spain counts positive for the spanish current account) and some minor factors like changes in currency reserves and the net transfer balance (e.g. when a Spaniards works in Germany and sends money to Spain, counts positive for the spanish current account).

Germany, that had negative current account balances after the German reunification 1990, managed to return to positive values with the introduction of the Euro.

(1.2) Ways to improve the current account balance

An improvement of the current account for the PIIGS countries is one way of obtaining growth and calming down financial markets and the spiral of debt and high interest rates. The typical methods for obtaining a better trade balance or current account balance are:

- Devaluing the currency

- Replacing labour by a different production factors, like better technology.

- A reduction of wages.

- Liberalization of the labour market.

One country that got out of trouble via a positive current account balance was Argentina. With the Asia crisis 1998 low growth in Brazil lead to a sharp devaluation of the currency, whereas the Argentinian Peso was pegged 1:1 against the US dollar. With the time cheaper Brazilian products replaced Argentinian goods, but the Argentinian government removed the peg too late, which lead ultimately to the Argentinian default. Thanks to a cheap currency and to rising food prices, the main export article, Argentina managed to obtain strong surpluses from 2002 onwards and to get out of its troubles:

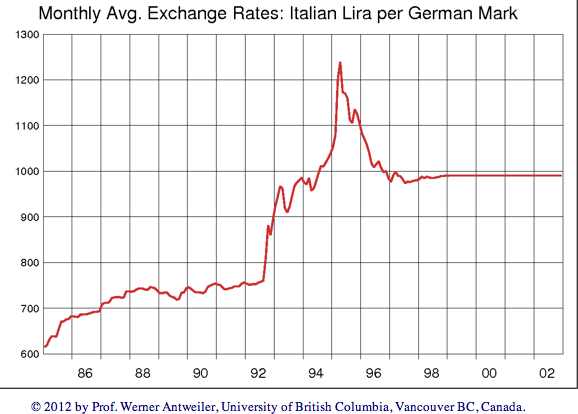

Italy was able to generate a positive balance in its current account especially in the mid 1990s, when after the reunification German inflation and interest rates were high and the Lira cheap against the Mark:

Devaluing the currency is not possible in the Euro era anymore and most economists think that an exit from the Euro would have unbearable consequences (see UBS).

Similarly a replacement of labour by a different production factor, like better technology, seems impossible. The PIIGS experience a serious credit crunch despite the expansive policy of the ECB.

(1.3.) Failed European wage adjustments as reason behind the current account imbalances

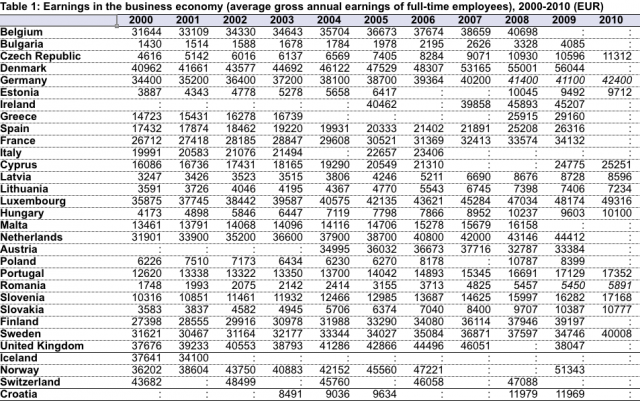

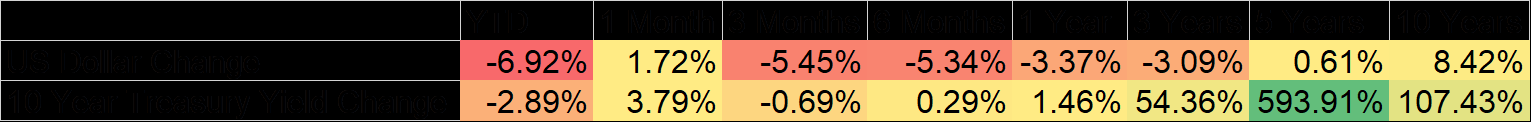

The reasons for the strong current account imbalances in the Euro zone were the strong wage rise between 2000 and 2007 in the PIIGS and the low increase in Germany (based on Eurostat statistics):

Whereas German wages increased only by 20% between 2000 and 2010, Greek employees doubled their salary and Spaniards and Portuguese improved by 50%.

German GNP fell from 254% of the European average in 1990 to 129% in 2002 (Bosch, Weinkopf, page 54). The main reason was the complete collapse of the Eastern German industry after the loss of competitiveness due to the introduction of the Western German Mark and the following over-investment into Eastern Germany including a tax-induced housing bubble that busted some years later. Many workers left the suffering Eastern Germany. The increased labour force caused German unemployment to rise to 9.4% in 2004, higher than in many European countries, whereas before 1990 it always had a far lower unemployment. More supply in the labour market lead German wages rise very slowly. Consequently Germany saw a very low growth between 1995 and 2005.

German real wages stagnated between 1990 and 2008. Another country has shown the same agony: real wages decreased by 2.4% in Italy between 1991 and 2010. Together with the already high Italian debt level at the Euro introduction this low increase of purchase power prevented that Italy fell into the trap as same other peripheral countries, namely Portugal, Ireland, Greece and Spain.

Since the Spanish construction boom has ended it has become clear that Spanish wages have risen too much. A quick readjustment of Spanish companies and a radical reduction of wages is not possible, therefore the unemployment rates have risen to pre-Euro levels:

At the same time Spanish unemployment was rising, the Spanish CPI continued to increase topping in September 2011 at 3.14% which showed that Spain was in mild stagflation. After several countries (including the US) showed some stagflationary tendencies after the cost-push inflation of the Arab spring, the euro zone tumbled into a recession further pushing the Spanish unemployment rate further up.

With the CPI YoY rate has recently decreased to 2%, trade unions and Spanish law (Keynesians “downwards stickiness”) make it difficult to reduce wages the Spanish stagflationary environment continues (certainly compared with the stagflations in the 1970s the inflation rates are relatively low, but still too high compared with the unemployment increase).

Part B: Generating growth via investments ?

In the previous part we have looked on a positive difference between exports and imports. In order to create such a difference, better technology and more capital via investments are needed. Since 2000, however, most PIIGS were on a consumption and house buying run, they did not save enough in order to be able to finance investments. Foreign funds are repatriated from the PIIGS so that even less capital exists. In the following we will on further details on the real estate crisis and its banking part.

(2) The Real Estate Crisis

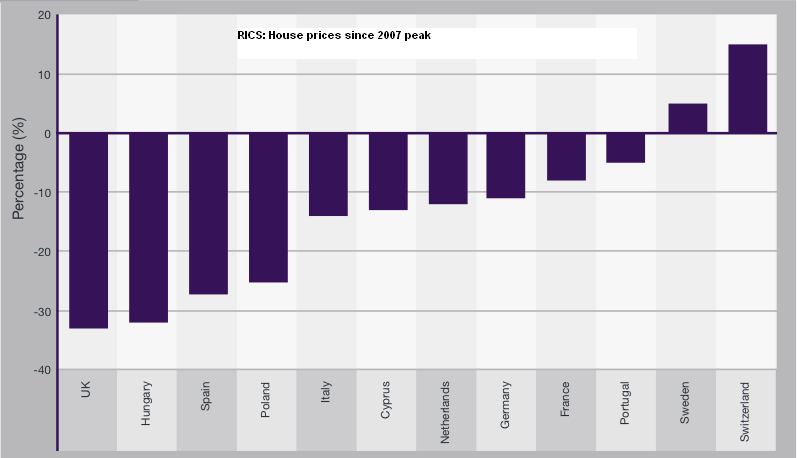

The main driver of internal investment is construction. Ireland, Spain and Portugal saw a housing boom between 1998 and 2007. Prices in Spain and Ireland rose by 3 to 4 times, whereas they increased by 40% in Switzerland and nearly stagnated in Germany (source SNB):

The RICS house price statistics shows the following changes since the peaks of 2007:

Spanish house building hit a peak of 665000 units in 2006 and went down to 63000 in 2010 and 55000 in 2011 (RICS page 57). Developers and banks sit on many unsold properties, prices have come down to 2004 levels. Similarly as in the US, and not like in the UK or Switzerland, there is an oversupply in the Spanish housing market.

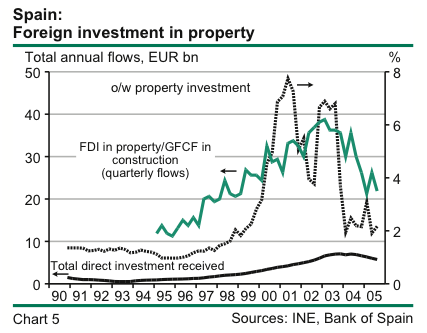

In a paper from 2006 BNP-Paribas gives the reason for the bubble in the following points:

- Different generations do no longer live together.

- A rural exodus has driven house prices in the centers higher.

- migration from other European countries, the migratory balance increased by 800% between 1998 and 2002, whereas it decreased in Germany by 35%

- Foreigners (especially britons) bought up to 40% of the houses in the coastal areas. This foreign investment in property helped to push up the spanish balance of payments.

- The housing bubble has led to a virtuous cycle: GDP to which housing directly contributed 10% and income grew strongly. With rising house price people felt the wealth effect, consumer confidence and spending went up.

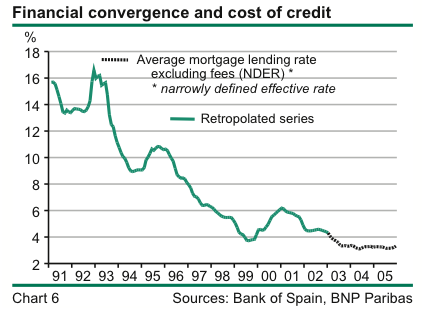

- Lower inflation in Europe since 1995 thanks to cheap imports from the emerging markets and slow growth in Germany had as consequence that the ECB provided cheap money to Spanish banks, whereas during the early 90s the Peseta was weak and especially imported inflation was very high. Given the rising house prices and wages this led to negative real interest rates in Spain and housing became even more interesting.

- Spanish banks managed to securitize many mortgages and sell these products to foreign banks when local deposits were not sufficient any more.

(2.2.) When will Spanish property prices rise again ?

Similar to the US property market today the supply of Spanish real estate is too high, income to value-ratios are too low.

(2.3.) Italy, France and Belgium the next to tumble into a real estate crisis ?

Ireland, Spain, Portugal, the Netherlands and Denmark have started the de-leveraging (according the survey from Lloyds) , whereas some other European countries remain sitting on high house prices. These countries are especially Belgium, France, Italy and still the Netherlands, where housing costs as part of the income are excessively high (source Economist).

(3) The Banking Crisis (Real Estate Part)

Still to be completed. Here some links on which we will base.

Vicious cycle to follow the virtuous cycle

Part C: Generating growth via government spending ?

(4) The Demographical crisis

Most European countries see their population shrink, the ratio between working population and retired people is increasing.

(5) Structural defects crisis: How quick reforms can solve the problems of competitiveness ?

The Euro Plus Pact of March 2011 counters at least the fourth point of our list above, the liberation of the labour market. It obliges member countries to abolish wage indexation, to increase their pension ages and to various further increases of their competitiveness. According to the Euro Plus Monitor Report of November 2011 some countries have made progress in implementing these competitiveness rules.

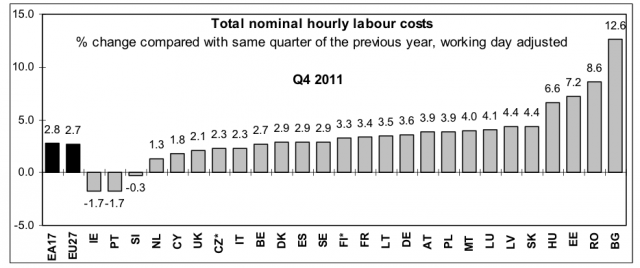

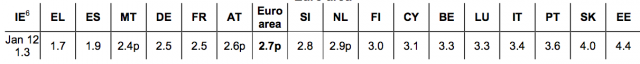

Nonetheless the Eurostat release for Q4/2011 has shown that Greece, Portugal and Ireland are the only peripheral countries of the Euro zone that have already started to cut their labour costs. Both Spain and Italy have seen increases:

(6) The Sovereign debt crisis

On March 2, 2012 the countries of the Euro zone and several EU countries signed the “Fiscal Compact”, an intergovernmental agreement that prevents that the structural deficit of one country exceeds 0.5% of the GDP. Fines of 0.1% of the GDP will be enforceable by the European supreme court. A violation of the maximum total public deficit of 3%, decided in the Pact for Stability and Growth, will lead automatically to sanctions except that a qualified majority of members countries oppose them.

The exact definition of “structural deficit” led to some discussions between the German ECB member Asmussen who wanted a stronger definition, whereas Keynesians insisted that Government spending is an important driver of an economic recovery.

The fiscal compact did not come at the right time. The right time would have been somewhere around 2006. Now this change in fiscal policy will lead a fiscal policy lag, the time to legislate the changes and to have impacts is too long.

(7) Balance of payment crisis:

Already now German, Dutch and Finish private companies and their central banks (key word Target 2) possess more and more foreign assets in the other countries of the euro zone.

(8) Banking crisis (sovereign debt part)

(9) Not optimum currency area

(Part D) “C” like consumer: Can the PIIGS grow via internal demand ?

The PIIGS’ consumers are currently in a balance sheet recession, their main aim is to reduce debt and not consumption.

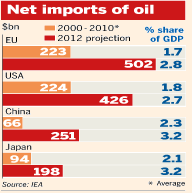

Oil price increases is an additional burden that the PIIGs cannot reach their pre-crisis growth (source FT).

10 Strong german economy and resulting strong Euro as second additional burden

To be completed.

Part E: Consequences

(11.1.) PIGS will become Germany’s second Mezzogiorno

Given the low unemployment figures in Germany and high levels in the PIIGS, a new migration wave to Germany has started in 2011 and will probably accentuate over the next decade. A recent portuguese news paper article about Germany’s Schwäbisch Hall let receive about 10000 job application from Portugal.

(11.2.) Deflation in the PIIGS and inflation in Germany and Switzerland to come

Italy and Portugal still see higher inflation than Germany or France, whereas Ireland’s, Spain’s and Greece’s sharp decrease in housing prices has started to show its effect in the inflation figures (below latest YoY CPI by Eurostat).

Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: 1970s,balance of payments,Banking Crisis,competitiveness,current account,deficit,ECB,Euro crisis,Eurobonds,Fiscal Compact,Fiscal Union,Germany Unemployment Rate,imported inflation,Keynes,Labor costs,labour costs,Northern Euro,optimum currency area,Peso,PIIGS,Real Estate,sector balances,Spain,Spain Consumer Price Index,Spain Unemployment Rate,Swiss National Bank,Switzerland