| To begin with, the economy today is absolutely nothing like it had been almost thirty years ago. That fact in and of itself should end the discussion right here. However, comparisons will be made and it does no harm to review them.

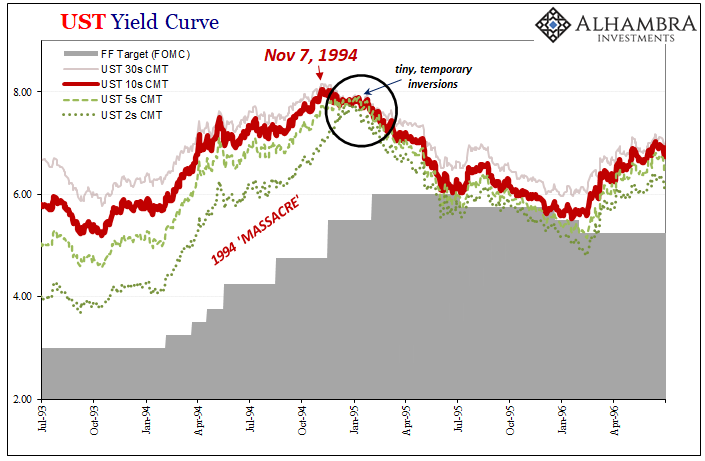

I’m talking about 1994, or, more specifically, the eleven months between late February 1994 and early February 1995. Fearing inflation (the only time in its history, including much of the Great Depression, the Fed didn’t fear inflation just so happened to be the first half decade of the Great Inflation; SMDH), Alan Greenspan’s FOMC got really aggressive. While the “maestro” started out with the usual (by today’s expectations) 25 bps, after three of those, one after another after another after another, by May 1994, the Fed doubled the dose. After doing so, however, it spaced out these now-fifties over two-meeting intervals, though only a pair of them before a walloping 75 bps in November 1994. The final one was again 50 bps early February 1995. |

|

| In less than a year, the fed funds target had been raised from 3.00% to 6.00%.

For US Treasuries, still today this is known as the 1994 Massacre. It’s not difficult to see why; the benchmark 10s went from a ’93 low of ~5.20% to just above 8.00% in November ’94. The 2s surged from ~3.70% all the way to around 7.70% in only a little while longer. The reason why this episode remains a such a huge part of Federal Reserve lore is the “soft landing” which followed after it. According to today’s mythology, Greenspan actually became the “maestro” when he aggressively stomped out inflation with the aforementioned rate hike program then nimbly and judiciously backing off before his “tightening” had gone too far. That’s the story, anyway. You’ll undoubtedly notice the similar outline and hoped-for proportions, including for what Jay Powell’s Fed shooting toward the same set of results – market to economy, an end to inflation leading into a soft landing of prosperity. |

|

| A befitting label all his own awaiting its completion.

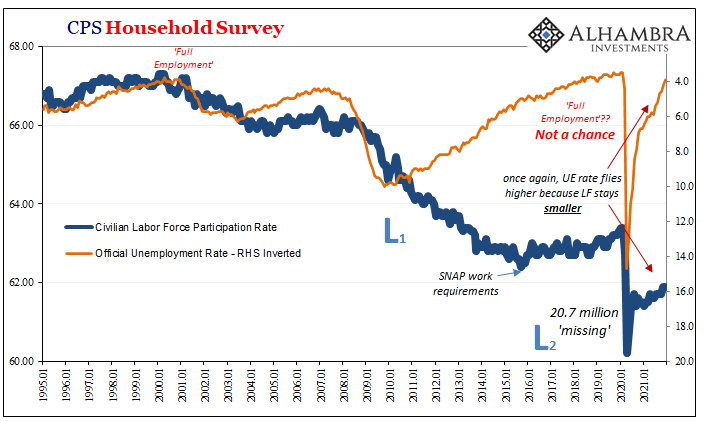

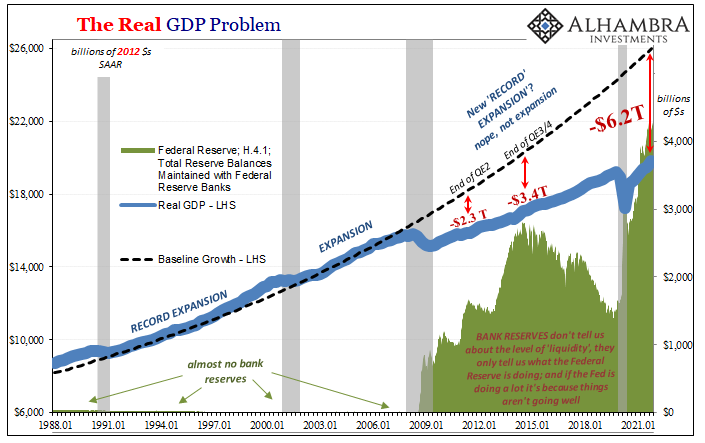

Setting aside serious questions as to whether there were any real inflation risks at all in ’94, here, however, our similarities end. For one, as I already wrote, we are sadly witness to an economy that is nowhere close to the ballpark for the one of the mid-nineties. Powell has already gone on record as claiming its close enough, when by any reasonable and honest standard you can see just how much he’s either wrong or lying. |

|

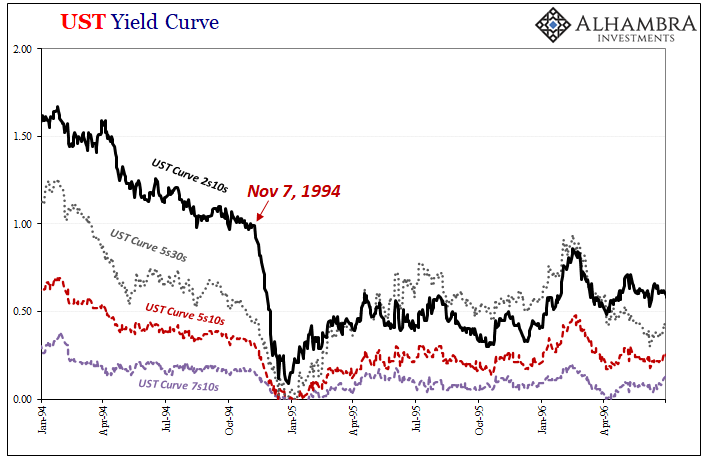

| The differences in the Treasury market are equally disqualifying. To begin with, while the yield curve did flatten beginning in ’93 anticipating Greenspan’s moves, it didn’t really flatten until the months following November 7, 1994 (below).

After that point, long run yields had already reached their top and were beginning to reverse. In other words, the comparison between then and now isn’t at all what the soft-landing crowd might be hoping. |

|

| Long-end pieces of the yield curve would eventually invert though by only the tiniest slivers (no more than a couple bps) and only over a couple weeks between late December ’94 and early January ’95 – while Greenspan was still hiking (so much for that “maestro” stuff).

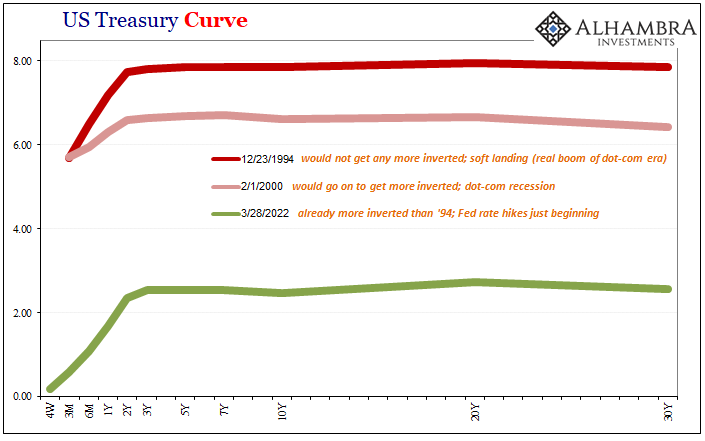

The UST curve would never really go any more upside down, and was already steepening again as rates fell further despite the Fed’s final rate hike in early February ’95. Whereas Greenpan’s Fed had already reached 250 bps of his eventual 300 bps rate hike total, Jay Powell’s Fed has just started and the Treasury curve (like eurodollar futures) is already more inverted across more of the curve than at any time in ’94 or ’95. So, if there was even the slimmest chance that ’22 ends up similar to twenty-seven years ago, even then rates would be about to fall from here. |

|

| Any steepening which would then happen of the wrong kind (therefore nothing like 1995 and after). One more time, the economy of today is in no way similar to the economy back then.

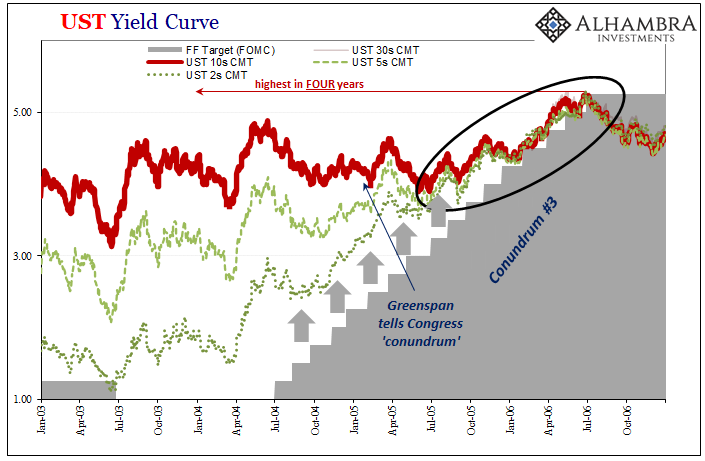

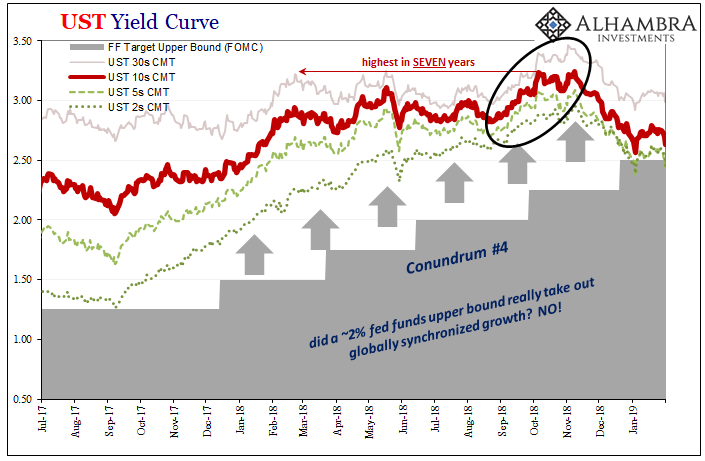

The Fed has barely begun and already inversions, a pretty clear nod to this fact. A weak and fragile global system beset first by no recovery following the last official recession in 2008 which was then piled onto (in all the wrong ways) by 2020. Today’s inversion regime isn’t about rate hikes, and the current reshaping of the curve shares far, far more in common with the pattern of Treasury market behavior witnessed beginning with early 1990, repeated throughout 2000, again in 2006-07, or finally 2018-19. See below: the curve of today has already gone further than its worst of ’94, sharing far more already with early 2000’s (or early 1990, if you prefer). We could only hope for something like the 1994 Massacre. |

|

|

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Alan Greenspan,Bonds,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,inflation,Markets,newsletter,rate hikes,U.S. Treasuries,Yield Curve