There is little doubt that the Federal Reserve will ease monetary policy at the conclusion of the FOMC meeting on July 31. We never thought the chances of a 50 bp move were anything but negligible, though even at this late stage, the market appears to be pricing in about a one-in-five chance.

Although a minority, and maybe worth a dissent or two (Rosengren? George?), we are sympathetic to those Fed officials that do not see the urgency to ease monetary policy. Even though Q2 growth slowed, the 2.1% pace, with more than a 4% surge in consumption, is above-trend growth, the Fed’s estimate of the non-inflationary rate. Investors will likely learn at the end of next week that job growth slowed in July. Non-farm payrolls are expected to have grown by 169k non-farm payrolls according to the median forecast in Action Economics survey (after 172k average in the first six months and 223k average in 2018). Nevertheless, it remains sufficient to absorb the new entrants and keep the unemployment rate near the lowest in a generation and underpin average hourly earnings at the upper end of a multi-year range.

The deflator of personal consumption expenditures is below the 2% inflation target, and the Fed sees this as giving it scope to reduce rates and take out an insurance policy to extend the expansion. The question is at what cost?

We are dismayed that the Federal Reserve itself has not mounted a more robust defense against accusations that it is a murder, that it habitually kills recoveries. The last three business cycles did not end because the Fed asphyxiated the expansion. Instead, they ended as a result of financial crises that had a negative feedback loop to the real economy. The saving and loan crisis, the tech bubble and the Great Recession ended their respective business cycle rather than the end of the business cycle, causing the crises.

Instead, the Federal Reserve seems to be running into its fate, like Oedipus of the Sophocles’ plays, even as it seeks to avoid it. It is as if Hyman Minsky’s insight was forgotten as soon as the expansion began. Among other things, Minsky taught that financial stability produced financial innovation and encouraged leveraged that leads to instability. This seems to be a greater risk than the Fed tightening too much.

It is not clear where the next financial crisis will arise. In the popular press, collateral loan obligations (CLO) and the increased share of BBB-rated corporate bonds appear to receive most of the attention. There is also a less often expressed concern that some of the financial products give an appearance of liquidity even though it may be more illusory. The problem may not be appreciated until conditions are stressed. Even without stretching one’s imagination, one can see how under such conditions, the contagion could quickly spread to more truly liquid (and safer) assets. That said, financial crises often seem to arise where people are not looking.

Taking an insurance policy might make sense under certain conditions, but the uncertainty that some Fed officials speak of does not seem amenable to preventative action. It seems clear, for example, that most of the slowdown in China is not related to the trade tensions. Unless the decline in the fed funds target rate translates to lower consumer borrowing costs (e.g., credit cards, student loans, car loans), it is not obvious how a Fed cut will make up for the loss of aggregate demand. It is not straight forward that lower US rates will inoculate the US from the disruption of a disorderly Brexit, for example.

Another type of insurance is arguably more relevant now. It is moral hazard. The so-called put by the Federal Reserve is very much in play. The eagerness to cut rates, seven months after last raising them, in the face of above-trend growth, full employment, elevated measures of valuation in the equity and bond market tell risk-takers and stretched borrowers and creditors that the central bank has their back.

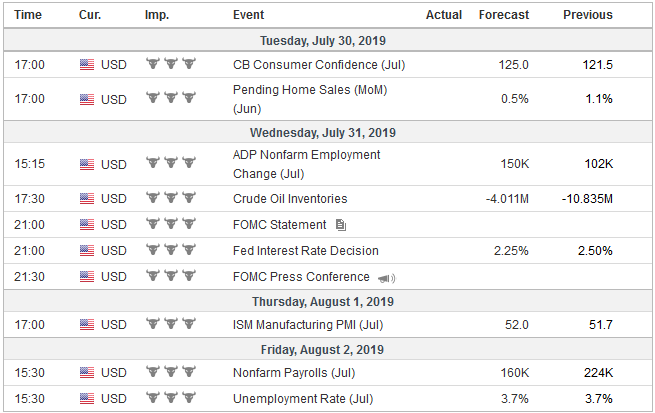

United StatesThe Fed has hamstrung itself. Congress gave it a mandate of price stability, but it eschewed a quantifiable definition for nearly 100 years. Greenspan’s summed up price stability as the rate of inflation that does not impact business decision-making. The Fed adopted a 2% inflation target (for the headline PCE deflator, not the core, though officials often emphasize the latter), but it has made a fetish of it—pursuing the letter of its self-chosen definition while sacrificing the spirit. The US has achieved price stability and at a level a little below the target, which is entirely subjective and not scientific. Many of the major countries have adopted a similar target, but the basket of goods they measure have marked differences. Rather than bemoaning the elusiveness of the inflation target, the Fed should declare victory. Full employment is in hand without elevated price pressures. Nevertheless, the Fed is determined not to break its pattern, and we expect three rate cuts by the end of Q1 20. While several other major central banks are likely to ease policy over this period, the US has scope for deeper cuts. The rotation of votes among the regional Fed presidents will likely see a somewhat more dovish cast to the FOMC. Alongside the cut on July 31, we expect the Fed will also stop its balance sheet unwinding six weeks earlier than it had anticipated. To continue the unwind while cutting rates seem to be at cross-purposes and something we think the Fed has intimated would be unacceptable. |

Economic Events: United States, Week July 29 |

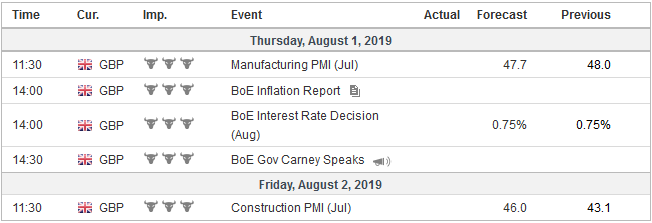

United Kingdom

|

Economic Events: United Kingdom, Week July 29 |

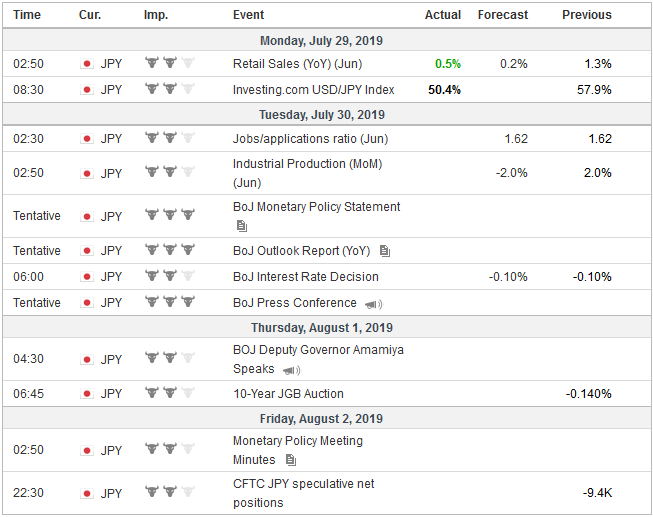

JapanThe Bank of Japan’s task is no less arduous. What can it do? Neither the size of the central bank’s balance sheet nor the continued increased has done much to lift measured inflation. The operating environment is becoming more treacherous: US-Chinese trade conflict, the slowing of the Chinese economy separate from trade, the elevated tensions with South Korea, and the easing by the Fed and ECB. Moreover, in two months, the national sales tax will be hiked to 10% from 8%. Past increases in the sales tax proved challenging for the economy. The showcase opportunity that the 2020 Olympic Games holds for Japan is another incentive to be ready for a new monetary and fiscal policies if needed. The MOF would issue new bonds, and the BOJ would buy more bonds after slowly pulling back (tapering? yield curve control?). The yen appreciated against the dollar around 5% in the Q2 19 at the extremes. Its 2.8% net gain led the major currencies and most of the emerging market currencies in the quarter. However, the dollar is testing the JPY109 area and a move above there would target the JPY110.50 (200-day moving average) to JPY111.00 area. |

Economic Events: Japan, Week July 29 |

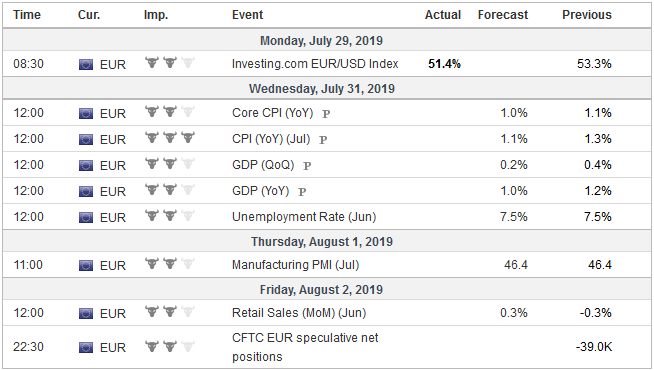

EurozoneDraghi’s assessment that the outlook was getting “worse and worse” on the eve of the anniversary of his “whatever it takes” pledge is surreal. And shortly before, the ECB meeting was concluding, Germany’s Social Democrat Finance Minister Scholtz rejected outright any pressure to increase fiscal spending. By acknowledging that the monetary measures that the ECB could take, may have diminishing returns, Draghi once again put the ball back in the politicians’ court; fiscal support may be needed. Admittedly, it still may difficult to fully grok negative nominal interest rates, but when faced with such conditions, Germany, the one with room and scale to meaningfully provide fiscal stimulus refuses. This is the rejection of Keynesian demand management through deficits in ordoliberalism manifesting itself again. Debt and guilt (schulden und schuld). A few hours before the Federal Reserve renders its decision on July 31, the eurozone will report three high-frequency data points that will be of passing interest. Last week’s ECB meeting has stolen some of the impact, and there will be another set of reports before it meets again. After the US reported a better than expected Q2 GDP, the attention swings to the eurozone. Growth was likely halved from 0.4% in Q1, and Q3 is not off to a much better start. On the other hand, unemployment probably remained at cyclical lows of 7.5% set in May. Last May it was at 8.3%. The eurozone will also report the preliminary estimate of July CPI. Oil prices were softer, and so was the euro (against most of the major currencies, but sterling!) which would seem to neutralize the heuristic elements. The median forecast in the Bloomberg survey sees the headline and core rate slipping 0.1% to 1.1% and 1.0%, respectively. |

Economic Events: Eurozone, Week July 29 |

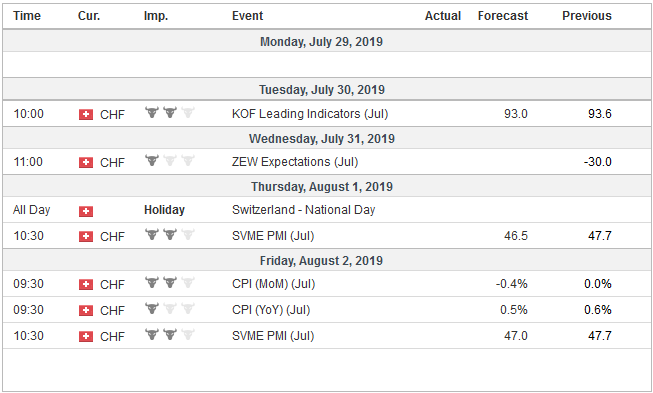

Switzerland |

Economic Events: Switzerland, Week July 29 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: #USD,$JPY,Bank of England,Bank of Japan,Brexit,Federal Reserve,newsletter