As May winds down, the light economic calendar will allow investors to take their cues from the evolution of three disruptive forces–trade, Brexit and the US economy.

With actions against Huawei and possibly a handful of Chinese surveillance equipment producers, the US raised the stakes. The retaliatory tariffs are effective on June 1, but Beijing has not formally responded to the moves against Chinese companies.

The Trump Administration seems to believe that the pressure from the tariffs and other actions will get China to capitulate to US demands. Officials were still playing up the likelihood that the two presidents meet on the sidelines of the G20 meeting in Japan at the end of next month. There is a relatively benign consensus narrative that the tariffs are a tactic, and, like at the end of last year, a meeting between Trump and Xi will jump-start talks again. However, there is nothing for China to gain at this juncture by talks. The US tariffs have already been lifted on $200 bln of its imports to 25%. The process has already begun to slap a 25% levy on the remaining Chinese goods that have escaped a penalty tax thus far, including popular consumer products like cell phones, tablets, computers.

Say what you want about Chinese trade practices, and no one seriously defends them, but the US red lines cannot be the basis of serious negotiations. Trump has indicated that the US will not accept a mutually beneficial deal because it needs to be compensated for past wrongs, and he has explicitly stated that he will not allow China to become the largest superpower. Many observers seem to think that because China speaks in communist ideological terms sometimes, it is monolithic It is not. The US demands cannot do anything but strengthen the hardline hawkish camp within China’s ruling circles.

A meeting at the G20 meeting plays into Trump’s hands. It could look as if China capitulated. Trump had demonstrated a flair for the dramatic, as he showed when he walked away from North Korean talks, and also again this past week when he walked away from the domestic bipartisan talks for an infrastructure initiative. The G20 venue and the spontaneity would be to Trump’s advantage. Chinese officials prefer a more scripted event.

Xi and Vice Premier Liu visited a rare earth facility at the start of the week. Intended or not, it was understood as a small reminder of vulnerabilities and asymmetries that China can exploit that are not captured in the macro data that US policymakers use to think that they can dominate the tariff escalation ladder. While the Trump Administration is stretching national security to justify steel and aluminum tariffs and threaten protection for the auto sector, the rare earths are truly essential for defense, as well as modern technologically advanced goods, including electric/hybrid cars, windmills, computer memories, cell phones, rechargeable batteries, and even some medicines.

Last year the US imported about 4100 tonnes of rare earths from China at the cost of about $175 mln, which is hardly even a rounding error for the bean counters who understand prices but not values. Most of the rare earths are embedded in the products it imports. US dependence on China for rare earths is well documented.

ChinaReports suggest that China will impose limits on exports to the US as a way to express its displeasure. There is precedent from nine years ago when in a dispute with Japan, China cut its access to rare earths. Given the complex supply chains and distribution channels, it is difficult for China to play this card directly. Just like it is not very easy to weaponize the yuan or China’s Treasury holdings, weaponizing rare earths could have broad impact, not the kind of laser focus that the PRC seems to prefer. This is not to say China can’t or won’t. The argument is less bold: the cost of doing so is high and therefore, likely at a higher rung in the escalation ladder. In China’s command economy, a quota is set for rare earth production. The most recent one for H1 19 was set mid-March. The mining quota was set at 60k tonnes in H1 19, which is down nearly 18.5% from a year ago. The smelting and refining quota was cut by almost 18% to 57.5k tonnes. The decline partly reflects the high quotas from the first part of last year, which were later balanced with lower quota in the second half. The 2018 quotas for the entire year worked out to be 120k tonnes of mining and 115k tonnes of processing. The quotas for the second half are expected to be announced by the end of June. A date for the trade talks to resume has not been set. The rhetoric remains bellicose. Reference in Chinese state media about another “Long March” and the importance of “self-reliance” are meant to pull on the nationalist strings. The trajectory of developments since the end of the tariff truce does not appear to have run its course yet. |

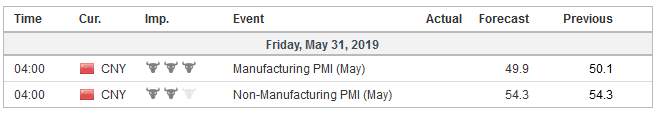

Economic Events: China, Week May 27 |

United StatesIt might not be until later in the year, maybe Q4 that may be the crunch time. Domestically, the Treasury’s ability to maneuver around the debt ceiling will be exhausted, if not addressed and the acrimony between the President and the Democrats is as intense as ever, making the necessary bipartisanship challenging to envision. The 180-day grace-period on auto imports will be exhausted. The 25% tariff on imported Chinese goods will begin being felt by American consumers, even if households purchase more services than goods. Separately, but not wholly unrelated, is the accumulation of evidence that the US economy is slowing markedly here in Q2. China’s economy also appears to have lost momentum recently. April industrial output and retail sales were weaker than expected and the May PMI that will be released next week is expected to show further slowing and pick up the first sentiment readings since the end of the tariff truce. Most observers had recognized that 3%+ Q1 US was not sustainable, and, in particular, the contribution of trade and inventories would not be repeated. A weak flash Markit PMI and disappointing durable goods orders, even after the Boeing effect is taken into account. The Atlanta and NY Fed’s GDP tracker is pointing to growth 1.3%-1.4% respectively. The January fed funds futures contract implies an effective average rate of 2.07% compared with 2.38% presently. That could be consistent with 25 bp cut in the target range (to 2.00%-2.25%) and a 30 bp cut in the interest paid on reserves (currently 2.35%). |

Economic Events: United States, Week May 27 |

The Federal Reserve has done nothing to encourage these views. The softness of core inflation is seen as temporary. The minutes from the last meeting and comments from several Fed officials, including the leadership, seemed to underscore that it remains comfortable with the patient, wait-and-see attitude. It did not talk about rate hikes when Q1 GDP overshot expectations, and it does not appear particularly concerned about some of the recent high-frequency data.

Some reporters try to play up the differences among the Fed officials, but there have been no dissents. The President’s criticism of the Fed, including the calls for dramatic rate cuts and a resumption of its asset purchase program, has, if anything, encouraged the officials to close ranks. This seems more the story than the different ways officials respond to different questions.

The tax cuts on corporate profits and household income have been succeeded by tax increases on imports. Reports and anecdotes suggest the result has been higher prices for many of the goods that have been hit with the tax. Even if when a 25% tariff on the remainder of China’s exports to the US hits, the impact on measured inflation is likely to be modest. The price of goods that reach the US shores is a fraction of what the consumer pays. The product is stored, shipped, insured, marketed, and every person along the way needs to be fed.

Profits margins may be squeezed in some areas. The price increases may not be sufficient to boost measured inflation very much, but it may be enough to reduce demand on the margins, at least until alternatives can be found or developed. To say the same thing in a slightly different way, the impact of the tax increase on imports will likely be more a headwind to growth and an accelerant of inflation.

A third issue that has vied for attention is Brexit. A new chapter in the history of the UK’s relations to Europe is about to begin. After nearly three years since the referendum, the UK has still not decided how it should leave the EU. The government spent 18 months negotiating with the EC and produced a Withdrawal Agreement that did the seemingly impossible by uniting Parliament in opposition to it. Unable to go forward with a divided party, May has reluctantly agreed to step down.

Investors have been anticipating this and recognize that her successor will most likely be someone who wants to renegotiate the Withdrawal Agreement, which the EC rejects, and leave the EU in any event at the end of October. This increases the risk of an exit without an agreement and sterling has shed nearly six cents since the beginning of the month. Sterling snapped a record 14-day losing streak against the euro with a small (~0.25%) gain ahead of the weekend.

It will likely take the Tories several weeks to sort things out. Even when it does, the sailing will be anything but smooth. Perhaps no one can square the circle: A sharp break with the EU and still honor the Good Friday Agreement. After losing its parliament majority, the Tories are able to govern through an agreement with the Democrat Union Party from Northern Ireland. A new Tory leader and Prime Minister would have to re-negotiate a pact with the DUP. If this is not possible, new elections would likely result.

Another moving piece in all this is that there will be a new configuration of the European Commission. It will arise out of the election for the European Parliament, whose results will be known before the markets open in Asia on Monday. It will take some time to get a sense of the distribution of posts and assignments. There are also other positions, like Draghi’s replacement at the ECB that will part of the great horse trade of European politics. The point is that by the end of October when the UK ostensibly leaves the EU, seven months after the initial intention, there will be a new European Commission and a new ECB President.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Brexit,China,Federal Reserve,newsletter,Trade,US