The last FOMC meeting of 2018 is at hand. After hiking rates three times in 2017, the Fed signaled that four hikes were likely this year and with a widely expected move on December 20, it would have fully delivered, though many steps along the way, skeptical investors had to be led by the nose, as it were, to minimize the element of surprise.

The famous dot plot of the Summary of Economic Projections has long shown that most Fed officials anticipated only three rate increases in 2019. This clearly implies moderation from the quarterly pace of hikes this year. This is not news.

Before April 2011, the Federal Reserve did not hold regular press conferences. This was more than two decades after William Grieder’s tome, The Secrets of the Temple, which captured and cast light on what was a fairly secretive institution. A combination of the Great Financial Crisis, the policy response, and the personalities at the Fed at the time led to Bernanke holding informal and then formal press conferences. Yellen maintained the pattern of holding press conferences at meetings at which the forecasts were updated. Rates have only been changed at meetings that are followed by press conferences. Yellen suggested that the Fed could and would call a press conference if it decided to change rates and none had been pre-scheduled. This never seemed particularly practical and never took place.

The Fed holds eight meetings a year. The forecasts are updated once a quarter. The Fed hiked in December 2015 and December 2016, before hiking rates three times in 2017. With only four press conferences a year, the Fed was limiting its degrees of freedom unnecessarily. As the Fed increased the pace of hikes, some greater latitude was advantageous. Going forward, the Fed Chair will hold a press conference after every meeting. The fewer anticipated rate increases implied a moderation in the pace, and the increased frequency of press conferences, imply greater flexibility.

What is new is when the market thinks the Fed will pause. The market never has accepted that the Fed would hike rates three times in 2019, but since the November 8 through the middle of last week, the implied yield of the January 2020 fed funds futures contract ( a good read into expectations for the end of 2019) tumbled 44 bp to 2.515%. Recall that the contract settles at the average effective fed funds rate (weighted by volume) which recently is about 2.20%.

The effective rate was initially around the middle of the target range, but in recent months is firmed to the upper end. The top end of the range is the rate at which the Fed pays for reserves. Although the Fed refers this as IOER, interest on excess reserves, the fact of the matter, which is often obscured, is the Fed pays interest on required reserves as well. In any event, to reinforce the cap, in September, the Fed only raised interest on reserves by 20 bp, while hiking the range by 25 bp.

The FOMC was so concerned about this that the recent minutes indicated that the Fed was prepared to move before the December meeting if necessary to adjust the interest on reserves further. The bar to such a move was quite high and has not been reached. It would have required the Fed to cut the interest on reserves while intending to hike rates again on December 20. The seemingly contradictory signals could have confused market participants.

The Fed will likely repeat the September maneuver this week, raising the interest it pays on reserves a little less than the overall hike of 25 bp. If it increases the interest on reserves by only 15 bp instead, it would be seen a dovish hike by investors, we expect. Investors will also assess the rate move through the lens offered by the Summary of Economic Projections. The Fed does not provide forecasts like the ECB or the Bank of England. Each member of the Board of Governors and each regional president submits their own forecasts, and a range and median are quickly derived. These are what is referred to as the Fed’s views.

Answers to two questions will be the immediate focus. How many rate hikes are anticipated in 2019? What is the anticipated long-term rate, which is understood to be the controversial neutral rate? In September, the median forecast for year-end 2019 was 3.125%. The dispersion of forecasts was wide, with one official seeing as appropriate no more hikes after September and one official seeing four increases in 2019 as likely necessary. The median judgment of the neutral rate put it at 3.0% in a 2.50%-3.50% range of estimates.

The fourth quarter has been a challenging period for the market’s handle on the Federal Reserve. In early October, Powell emphasized how accommodative monetary policy continued to be, and many observers took this as an aggressively hawkish signal as there was quite a bit more tightening that would be delivered. Many blamed the downdraft in equities on these comments. Then several Fed officials, including Powell, tried to balance these comments, and the market took it as dovish, though equities have been unable to recover and the 2-10 year yield curve has continued to flatten.

We suspect the official view of the economy has not swung as dramatically as implied yields in the futures market. That does not mean that the dot plot cannot change materially. Consider the impact on the median if the five officials in September that thought a target range of 3.25%-3.50% or more would be necessary shaved their forecasts. At the same time newly confirmed Governor Bowman might strengthen the center. The one official who thought there did not need to be a rate hike after September may have to drag it up if there is a December hike.

United StatesAnother non-economic consideration is the steady stream of criticism of Fed policy from the President of the United States. Few observers expect that Trump’s admonishments will impact Fed policy. There are some who do think that the Fed “blinked,” but most seem to accept that the Fed is moving in a less hawkish direction on its own accord, due to the softening of price pressures and slowing of economic activity. They see Trump’s remarks as primarily, political using the Fed as the whipping boy for equity market stumble. It does seem rich to argue that preserving the Fed’s independence strengthens democratic institutions, but in the current context, it is the limits on executive power that defends the delicate system of checks and balances. Many observers expect a dovish hike by the Fed. The less dovish case can be cast as a three-legged stool: Above trend growth, low real interest rates, and a tight labor market. The US economy has indeed slowed, but no one really thought that the 4.2% Q2 or even the 3.5% pace of Q3 was sustainable. Based on demographics and productivity, trend growth in the US is likely around 2.0%. The Atlanta Fed sees the economy tracking 3.0% here in Q4, while the NY Fed’s model says 2.4%. For all the doom and gloom that is reported, private sector forecasts appear to be splitting the difference. A point that we keep coming back to is that the real (inflation-adjusted), policy rate just reached zero because headline CPI in November fell to 2.2% from 2.5%. In past cycles, a negative real policy rate was needed to facilitate recovery. US labor growth remains robust, and the most recent weekly initial jobless claims fell to 206k. The cyclical low was set in mid-September at 202k. Even with the job growth disappointing a bit in November, Moreover, non-farm payrolls averaged 206k this year compared with 175k in 2017. |

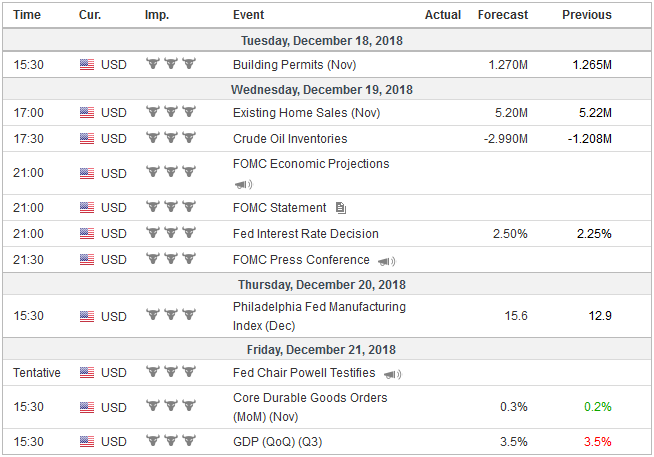

Economic Events: United States, Week December 17 |

EurozoneThe US economy is the envy of most other major countries. The Fed’s tone is likely to offer a stark contrast to that of the ECB last week, where Draghi acknowledged that the risks for moving to the downside. Within 24 hours of Draghi’s press conference, France reported its flash PMIs for December all fell below the 50 boom/bust level. Germany’s showed that the recovery from the Q3 contraction is lackluster. The Fed’s economic assessment is likely to differ with the Japanese government, which is expected to cut its FY2019 GDP forecast to 1.3% from 1.5% made a few months ago. This is more optimistic than the BOJ and private sector that projects it to be below 1%. The Chinese economy also appears to have lost momentum in Q4, but both fiscal and monetary levers are being adjusted. Two other issues trade and Brexit appear to be frozen for the time being. China appears to be renewing its purchases of US agriculture (soy and, possibly, corn soon) and energy. It will lift the retaliatory tariff on US-made auto imports (mostly European brands). It also appears willing to modify its “Made in China 2025” timeframe, even if not the goals. China has also adopted more laws to defend intellectual property rights. A gap between China’s declaratory and operational policies is the source of much tensions and it will take some time to convince others that the gap has closed. Meanwhile, after the drama of the Tory Party failing to replace May, the situation is little changed: The Prime Minister has an agreement with the heads of the other EU countries. However, it does not have majority support in the House of Commons. The EC has shown no desire to re-open negotiations. This risks an exit without a Withdrawal Agreement. It is among the most disruptive scenarios. In the days ahead, the EC will announce additional preparations for it. There is likely to be little development until next year, but the is increasing speculation of a second referendum, and we note that at the PredictIt.Org, an event-betting website, the odds have turned in favor of the UK not leaving the EU on March 29, 2019. |

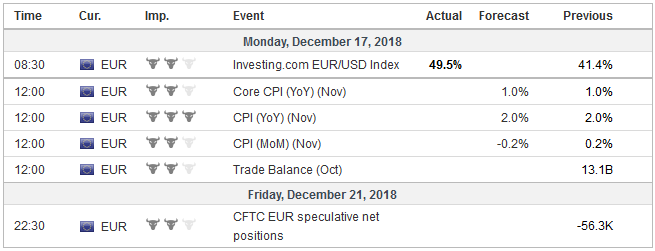

Economic Events: Eurozone, Week December 17 |

Switzerland |

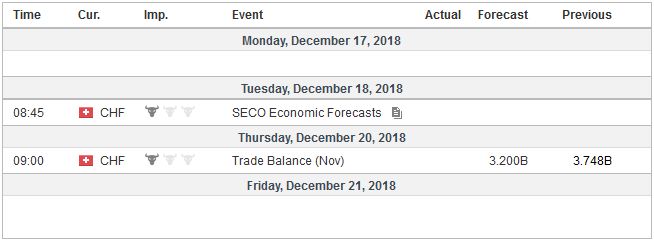

Economic Events: Switzerland, Week December 17 |

Tags: #USD,Brexit,China,Federal Reserve,newsletter,Trade