Often, and apparently wrongly attributed to Mark Twain is the observation that it is not what we know that gets into trouble, but “what we know that just ain’t so.” Now though, investors suffer from a different problem. Several processes are in motion, and there is little confidence in their outcomes. Among these are Brexit, US-China trade, the trajectory of Fed policy, and the EC’s efforts to enforce the agreed-upon budget rules.

United KingdomThe UK referendum in 2016 was supposed to be a vehicle that united, if not the UK, at least the Tory Party. It has taken a couple of years, but it now seems that there is a common stance and it is against the Prime Minister’s plan. However, when the history of the period is written, the crisis of leadership may feature prominently. The Tories badly botched the exit from the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (1992) and now its withdrawal from the EU is in shambles. Perhaps no one could have straddled the conflicting demands that emerged once the decision was made to leave. Perhaps the deficit in leadership aggravated a difficult situation. Unless the UK tries to unwind its decision to leave, which would seem at this juncture only possible with a second referendum (odds now by bookmakers is around 40%), it will leave at the end of March next year. The issue is whether it leaves with an agreement or not. The UK and EC negotiators reached an agreement in principle, and the strategy from 10 Downing Street seemed to be to deliver the cabinet and parliament a fait accompli. It is this agreement or no agreement. Gove refused the seemingly poisoned chalice of as Raab’s replaced reportedly because May rejected his demand that he be allowed to re-open negotiations with the EC. Nor is the EC open to new talk. The ball is in Tory hands, though not May’s. Outside of capitulating to the government, there are two main ways the party can rebel. There can be a leadership challenge if a sufficient number of members of parliament call for one. Plenty of opportunities have arisen, but no stalking horse or alternative have stepped forward. The Tories can also sink the government by calling a vote of confidence and then not supporting it. A snap election would be necessary. It would be disruptive, and the clock is still ticking toward the exit date. It is a risky strategy as one can’t be confident of the outcome. The cost of hedging sterling can be a function of two considerations: implied volatility and interest rate differentials. Three-month implied volatility is a 2.5-year high. Although exchange rates themselves do not look to be a mean-reverting process, volatility seems to be. However, another characteristic of volatility is that it is sticky. A high vol is likely to be followed by another high vol period. On the other hand, interest rate differentials have widened, and this makes it cheaper to use forwards to hedge sterling exposure as it would involve selling sterling (lower interest rate) and buying dollars (higher interest rate). The change in spot and the volatility last week means that the implied theoretical range for year-end (one standard deviation) stands roughly $1.2260-$1.3465 compared with $1.2465-$1.3550 a week ago. |

Economic Events: United Kingdom, Week November 19 |

United StatesInvestors never fully bought the Fed’s signal that three rate hikes were likely in 2019 and the gap between the market and the Fed has widened. The implied yield of the December 2019 fed funds futures contract has fallen seven basis points since November 1 to 2.755% and nearly 15 bp last week as it will begin the week ahead with a six-day advance in tow. Currently, the effective fed funds rate (which is what the contract settles at) is 2.20%. When we initially suggested the economy would slow sufficiently to get the Fed to pause in the middle of next year, this was earlier than most expected. Now, the market is more aggressive and leans toward a pause after Q1. Two hikes between now and the end of March 2019 would bring the effective funds rate 40-50 bp higher depending on if the September move of not raising the interest rate paid on excess reserves (and required reserves) is repeated. Powell had been criticized by commenting in early October that the fed funds target was still well below neutral. This was seen as unnecessarily hawkish. Separately, the fact that the interest paid on reserves and even the fed funds target range itself is not capping short-term rates (the secured overnight financing rate (SOFR) which officials have chosen to replace LIBOR finished last week at 2.28% is troubling many participants. The Fed chief explained last week why the risks were assessed as balanced, which is to say that the US economy is growing strongly but that there were potential headwinds on the horizon, like slower world growth, the accumulation of past hikes, and the fading of the fiscal stimulus. Yet even Trump’s appointments to the Board of Governors continue to suggest that additional rate hikes are appropriate. Some observers seem to make much of dovish comments by regional Fed presidents Bostic and Kashkari. However, they are the doves and have generally opposed the entire normalization process. Other observers emphasized Philadelphia Fed’s Harker’s comments ahead of the weekend that indicated he was not yet on aboard for a hike next month. Here too people seemed primed to find the news that justified their views. Harker has endorsed a December pause since at least early October (see here). A scenario that is beginning to take shape is a Fed pause after a hike around the middle of the year. The Fed would have to signal it was pausing, otherwise, the markets would not know until September or so (all meetings will be live next year in the sense of a press conference will be held following each). Given the average time between the last hike and the first cut, a window would still be open to a reduction in rates before the 2020 election. The Fed’s defense of their independence in the face of the president’s criticism, including continued rate hikes, means that a pre-election rate cut would be not as vulnerable to criticism of political motivation. |

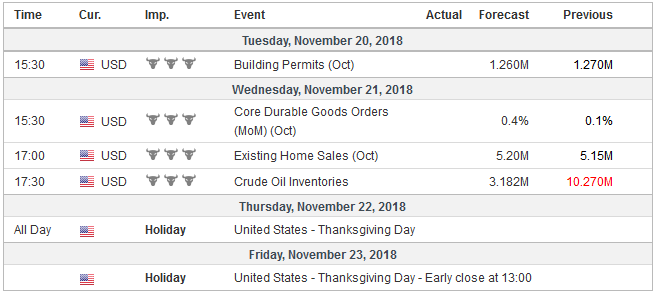

Economic Events: United States, Week November 19 |

EurozoneEuropean policy is in flux. To be sure, the European Central Bank will complete its net asset purchases at the end of the year. Then what? The ECB has pre-committed to not raising rates until after next summer, allowing Draghi to keep open the possibility that he would oversee the first hike since 2008 before his term expires at in October 2019. However, since September staff forecasts, growth has been weaker than expect and the flash PMIs, due at the end of the week ahead, are expected to show that momentum has yet to be rekindled. The euro has softened a little on a trade-weighted basis, but more importantly for the inflation outlook will be the roughly 15% drop in the price of Brent since the start of September. The market’s reaction to the December 12 ECB meeting at which the conclusion of the asset purchases will be confirmed, may be driven by the staff forecast update that could shave both growth and inflation forecasts. The ball is back in the EC’s court. Italy responded to the EC demand that the budget proposals be revised and brought back into alignment with the agreed upon rules. It essentially says it will not, but it seems open to some measures that would kick-in to assure that the deficit does not exceed 2.4% of GDP this year. In the middle of next week, the OECD will update their economic forecasts, and the EC will formally announce its budget assessment of all countries considered in violation of the deficit and debt rules. It may start excessive deficit proceedings against it could ultimately lead to a fine and a suspension of access to some EU funds. Spain and France may also be cautioned. |

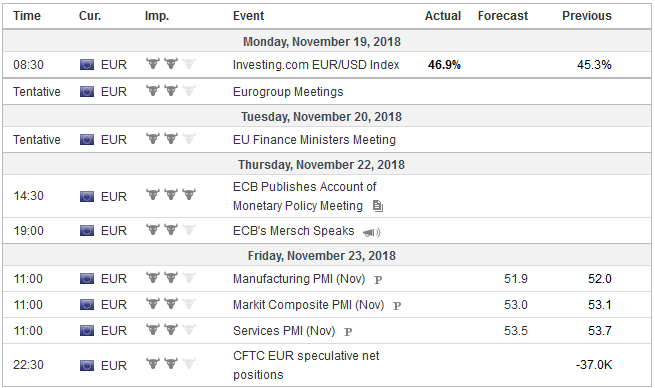

Economic Events: Eurozone, Week November 19 |

Switzerland |

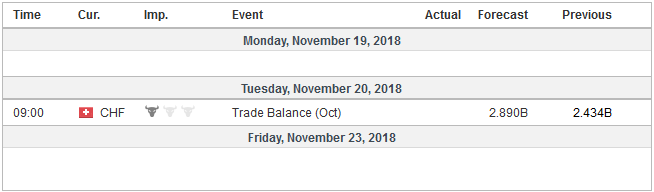

Economic Events: Switzerland, Week November 19 |

China

President Trump seemed to suggest a compromise on trade with China was possible, and many want to believe it. Trump’s willingness to read into China’s formal response a change of heart lends support to allegations that the US President is more interested in claiming successes than actually changing very much (e.g., NATFA 2.0 = mostly NAFTA 1.0 and TPP Agreement).

On the other hand, it may not do justice to the profound challenge that China is perceived to present by leading American intellectuals and policymakers. As Trump was playing nice for investors, the administration was participating in an attempt to revive the “Quad” (US, India, Japan, Australia), which is meant to counter the projection of Chinese military in the region. Vice President Pence gave another speech over the weekend at the APEC Summit that Chinese President Xi also attended. It seems clear that different spheres, including trade, defense, and development that the US is countering the rise of China’s influence.

There is another reason to be skeptical that the US and China will reach a substantive agreement. In the NAFTA 2.0 deal, which is also intended to be signed at the G20 meeting at the end of the month when Trump and Xi will meet, there is a clause that means little to Canada and Mexico, but which is significant on ideas that the trade agreement will be the template for future trade agreements. The clause essentially says that if one wants to have privileged access to the US market, it cannot strike a trade agreement with a non-market economy. A non-market economy is an unmistakable reference to China.

Nor would it seem consistent with Xi’s modus operandi to capitulate to US demands. If the real issue were the bilateral trade balance, the US would have accepted, so the thinking goes, China’s offer earlier this year to buy a lot more US goods and services. A deal in principle was struck with Treasury Secretary Mnuchin only to be rejected by Trump. So, of course, Trump to end the tensions that he had fanned in the first place. The US demands go well beyond trade and Xi is most unlikely to jettison the Belt/Road Initiative, for example.

Threats of more tariffs will not scare China to change in the desired direction. Chinese officials recognize that some of the same people in the Trump Administration were using similar tactics and rhetoric to arrest the rise of Japan in the early 1980s. The seemingly erratic US behavior supports those in China who want to disengage from the US. Arguably, there is an under-appreciated risk that the world begins shifting into two large camps, with both trying to make it an either/or proposition. It may take some time to solidify into blocs, and the trajectory is not set in stone (as an expression of some immutable law of the clash of the hegemonic and rising power), but that seems to be the path, leaving the old Chimerica concepts seeming quaint and fanciful.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: $EUR,Brexit,China,Federal Reserve,Italy,newsletter,Trade