It’s interesting, to me anyway, that an image of the Roman goddess Juno remains to this day on the logo of the Bank of England. There are many stories about her role as it relates to money, but what cannot be denied is that the very word itself came to us from her temple. The Latin moneta was derived from the word monere, a verb meaning to warn. Moneta was Juno’s surname.

One fable has it where the goddess’s sacred geese saved Rome from being sacked and destroyed, cackling loudly in the night so as to alert Roman soldiers of the presence of enemy troops so close at hand with widespread slaughter in their hearts. The great politician Cicero wrote that it was Juno’s commanding of a sacrifice (ut sue plena procuratio fieret) given in a temple that had alerted Romans to a forthcoming and devastating earthquake. He also chronicled in De Divinatione an earlier writing from Coelius that she had cautioned Hannibal not to carry off the golden column from her temple at Lacinium lest he lose the use of his remaining good eye (according to the earlier writing, he wisely heeded that advice).

| Juno Moneta came to be regarded in this way, a representation of sound practice and advice. Because of this, coins were made in her temple, giving us the modern words money as well as mint. | |

Obviously, the concept of money has evolved like everything else. One modern invocation was in the form of the central bank, those with and without Juno and her warnings in their logos. It was Walter Bagehot in the nineteenth century who at the Old Lady set down the rules, so called, of central banking in an advanced mercantilist economy. Writing in Lombard Street, Bagehot argued:

Most people, somewhat correctly, focus exclusively on the part where the BOE has no choice but to be lender of last resort. This lend freely at high rates mantra supposedly defines the opening chapters of the modern central bank textbook. To my mind, the more important, and relevant, section is what preceded that framing. The point of any policy is “not to advance to bankers.” A bank reserve though a bank liability has a stated purpose, which is more mercantile rather than purely financial. A bank reserve, like monere, is a verb. The topic is germane because if there is one thing the world has in robust supply it is bank reserves. They have been manufactured by central banks in almost every jurisdiction by the trillions in response to the global financial emergency. Reserves continue to be created by outlets like the Bank of Japan and the ECB even though that great crisis is already ten years into the past. Why? |

Inflation Europe, Jan 2007 - 2018 |

| Nobody can offer any good answers, at least those where bank reserves are treated as money. This difference has led to a whole lot of confusion, and constantly broken expectations. The ECB’s head, Mario Draghi, provided us with yet another clear example just last week on the occasion of that bank’s latest policy statement.

Draghi’s words overall were taken as dovish, though most commentary attributed that to a desire to be predictable and err on the side of caution – not becoming too aggressive in their otherwise burgeoning economic optimism. Perhaps ECB officials have finally become self-aware of their recent past history making that very mistake (raising rates twice in 2011 on the basis of the same diagnosis just as the whole European economy instead fell into re-recession). Thus, Draghi made what appears a contradictory assessment:

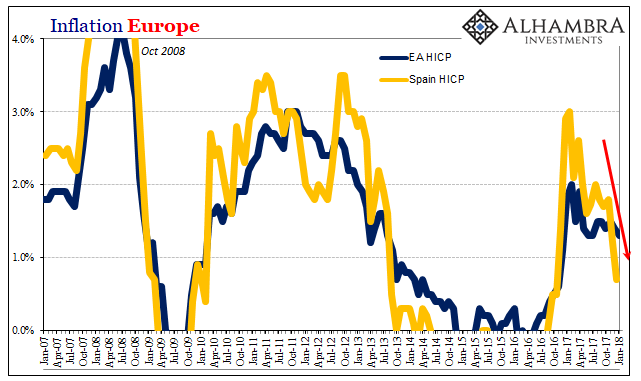

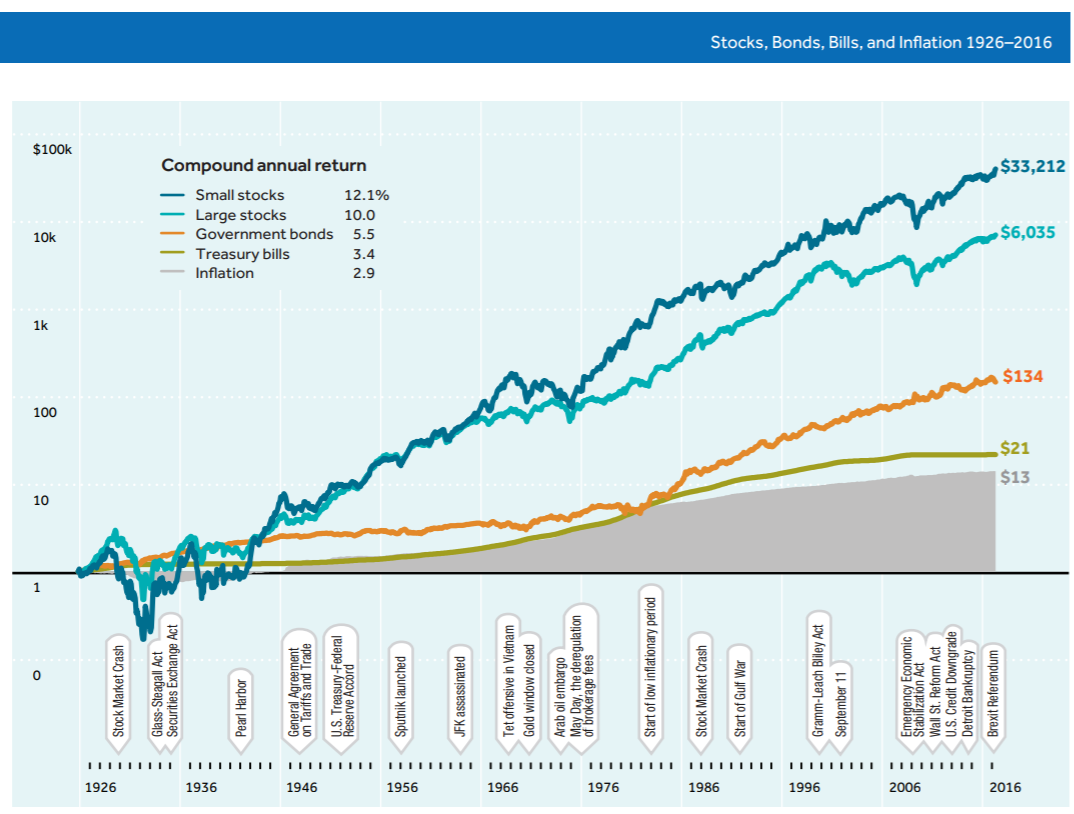

Huh? They are further strengthened in their confidence that inflation will in the future get up toward 2%, based on nothing today because price pressures “have yet to show convincing signs of a sustained upward trend.” Any ECB dovishness is the ancient voice of Juno wafting northward into Frankfurt, her flock of sacred geese greatly agitated by all the absurd nonsense. There is good reason for them to take a more cautious tone. Inflation rates have fallen hard in the places where they should be most accelerating. Spain and Italy, for example, are two of the majors from the Southern contingent that took the worst of the last decade. For Europe to be successful economically on the winds of ECB bank reserve creation, that’s where things should be moving sharply higher, especially inflation. |

Inflation Europe, Jan 2007 - 2018 |

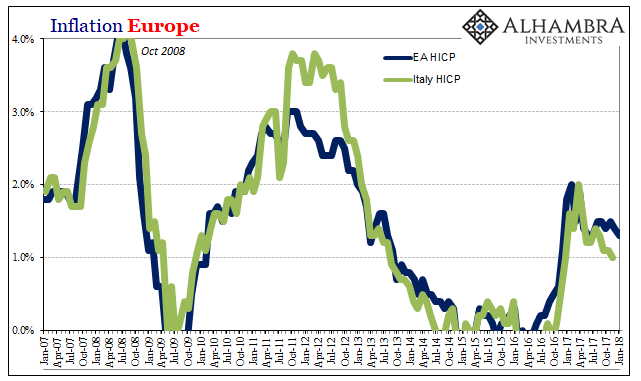

| While Italy’s January 2018 HICP inflation calculation hasn’t yet been released, it had already fallen back to 1% in December 2017. Spain’s is far more concerning. After registering a peak of 3% and what Mario Draghi wants to see on a sustained basis there, instead the rate decelerated back to 1.2% last month – only to collapse to 0.7% this month.

Overall, the HICP for the EA19 dropped down to 1.3% again. The core inflation rate, excluding prices of alcohol, tobacco, energy, and food, was for yet another month just 1%. It’s hardly changed from the lows in late 2014 when all this NIRP and QE began. |

Inflation Europe, Jan 2007 - 2018 |

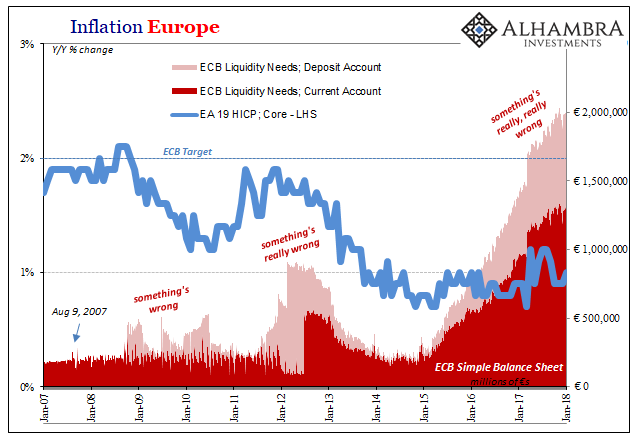

| This inflation stuff matters, quite a lot. It matters to begin with for Mario Draghi’s credibility as a proxy for the rest of the central bank’s policies. Without any evidence for his claim, his statement about future inflation can be reduced to: I know that inflation will accelerate because I know that inflation will accelerate. It’s on this basis alone that people follow his pronouncements, though they might not realize it.

More than that, inflation as a strictly monetary phenomenon is a check on the creation of trillions in bank reserves. Heeding instead Bagehot, a bank reserve cannot be money lest it find eventually its mercantilist purpose. If that had been the case over the last ten years through these numerous policy experiments, we would know it for sure via inflation. |

Inflation Europe, Jan 2007 - 2018 |

| Thing is, we do know it via inflation; it’s just not coming out the way Economists have surmised and continue to expect. Bank reserves have not done much if anything where they are supposed to really work. With inflation in Italy and especially Spain dropping far and fast you can bet the ECB’s newfound “dovishness” is grounded in nervousness, all public nonsense protestations aside.

There are gathering global indications including European inflation that whatever upturn the world was able to gain in 2017, it may not last much longer. It wasn’t even all that good to begin with, though it seems like it has been characterized often enough as the greatest expansion in history (OK, slight hyperbole fitting the hyperbole). The continuing issue is bank reserves and in the exact manner Walter Bagehot described a century and a half ago. Inflation is a warning about money therefore economic fragility, perhaps the remnants of Juno Moneta that after two and a half millennia survive still for more than just meaningless pictures on logos. |

Inflation Europe, Jan 2007 - 2018 |

Tags: Bank of England,Bank of Japan,bank reserves,central-banks,currencies,ECB,economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,inflation,Mario Draghi,Markets,money,newslettersent