The advent of open and transparent central banks is a relatively new one. For most of their history, these quasi-government institutions operated in secret and they liked it that way. As late as October 1993, for example, Alan Greenspan was testifying before Congress intentionally trying to cloud the issue as to whether verbatim transcripts of FOMC meetings actually existed. Representative Toby Roth (R-WI) quizzed the Fed Chair as to whether the rumors were true, mistakenly using the term “mechanical transcripts” which let Greenspan focus on it in the negative.

Even Milton Friedman’s old writing partner, economist Anna Schwartz, had had enough of what in the next decade would become famously “fedspeak.” On such a simple topic as this, she reasoned, Greenspan was taking it too far:

“The Fed has been lying about the transcripts for years. I could not discern whether [Greenspan] was talking about old transcripts or the regular meeting `notes’ prepared after the FOMC meets. As far as I could tell sitting in the room, Greenspan did not clearly and explicitly disclose the existence of written verbatim transcripts so that members of the committee understood what he said.”

It’s a pretty big commitment to privacy and privilege stooping so low as to argue the semantics over the manner in which records are created and kept. But that was how central banks did it back then. Even today, we don’t really know when the Fed shifted to interest rate targeting in the eighties; some say early on in that decade following their disastrous contributions to the Great Inflation; others say it came later. They’ve never clarified because?

Monetary policy particularly at points of extremes cuts both ways; on the one hand, it can be comforting that the central bank is following Bagehot’s ages old rules to lend freely at high rates. Markets do like backstops (or so-called puts, imagined as real). On the other, what does it say about how bad things are if any central bank is in the market and in a big way?

It is that view which prevailed for a very long time, and the one Greenspan was defending (without, of course, saying so) with his brand of theatrics in 1993. There is a lot to it, this idea that though it’s dangerous to stay out of dysfunctional markets it’s worse to confirm to the world that they aren’t working. No central banker wants to be the one to provide the markets its Oh Sh–! moment.

Ben Bernanke’s legacy contribution is intended to be the accomplishing of the opposite (it certainly can’t be QE or anything the Fed did in operational terms from the very beginning of the crisis). He believed it was better for market function where the central bank doesn’t just tell you what it’s doing, they tell you long in advance what they will do and for how long (assuming, as central bankers always do, that they know what they are doing at any timescale).

Some central banks still operate closer to the old model, though none are entirely all one way or all the other. Among those preferring stealth over broadcast is the People’s Bank of China. If you can figure out their presence, they haven’t done as good a job.

Though it is now two years in the past, I believe there are a couple things about January 2016 that are worth reviewing for their relevance to our current state. Because there was so much turmoil globally at that time, one of things that got lost in all of it was a brief but major move in what was then an afterthought regime. Most of our attention was focused, correctly, on crashing CNY.

By that point, even the talking heads on TV had figured out that when CNY fell it wasn’t some intended Chinese “stimulus” as they had asserted a few months before in August 2015. Whenever the currency exchange against the dollar dropped, it was bad everywhere. That immediately suggested the problem was bigger than China, and much bigger than CNY. Because the results were replicated all over the world (EUR, RUB, BRL, CHF, etc.), that all meant dollar, or really “dollars.”

Among the central banks trending more toward the Bernanke view, the Bank of Japan had undertaken more QE’s than anyone should have to count with that transparency in mind. Yet, on January 28, 2016, they shocked the global financial system by introducing negative interest rates (NIRP) barely a week after Haruhiko Kuroda had insisted to Japan’s parliament that they weren’t being considered.

“Something” had changed, as one Economist noticed at the time:

“It [BoJ] has gone on the defensive,” said Hideo Kumano, chief economist at Dai-ichi Life Research Institute. “It made this decision not because it’s effective, but because markets are collapsing and it feels it has no other option.”

| Japan’s NIRP didn’t work; at all. It was a decision that would continue to haunt yen monetary operations for some time, and it did little to staunch the global rout. In many ways, the imposition of negative rates followed closely what central banks have always most feared about openness. It had the practical effect of confirming that there was a massive problem, as well as where that problem was if not originating then at least where it was focused (yen basis swaps would continue to worsen, go more negative, for another year).

If the dollar was the issue, its Asian version or gravity was its epicenter. Other central banks responded with more subtlety. That didn’t mean they were perfectly hidden in their interventions, of course, only that they were more attuned to the reasons for not being so conspicuous. One part of opting for Greenspan levels of surreptitiousness is how ambiguity can be used positively. It’s therefore worth noting that BoJ’s NIRP panic came after HKD’s revelation for how it really was. |

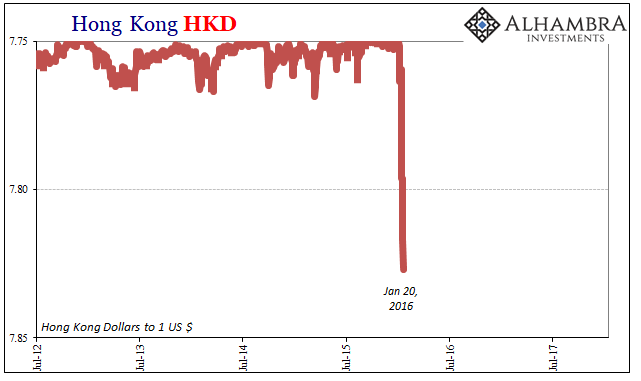

Hong Kong HKD, Jul 2012 - Jan 2018 |

| Again, lost in the craziness of those first few weeks of 2016 the PBOC wasn’t exactly operating in complete secrecy (above), but I have to believe they knew it wouldn’t be front page news, either. With oil and stocks on everyone’s mind, who would care that the Hong Kong dollar had gone ballistic (inverted)?

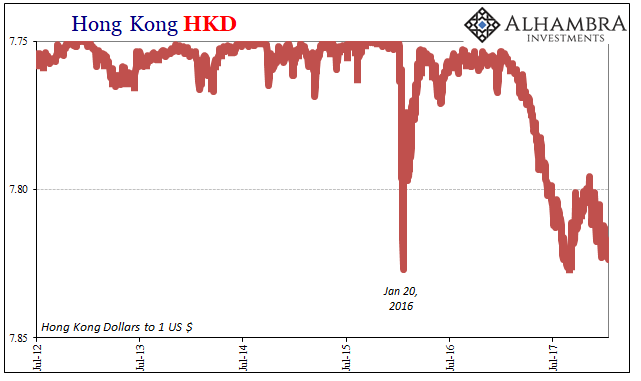

Furthermore, it worked. China had a dollar problem that they were able to partially offset without letting anyone know just how bad it was. Sure, CNY crashed that much further, but by early February (just after 2016’s New Year Golden Week had ended) the Chinese had apparently obtained enough “dollars” behind the scenes via Hong Kong to make it a bottom for the “rising dollar” situation as a whole. Their currency would continue to fall through the rest of that year, but the level of disruption corresponding to that decline was obviously diminished. If they could successfully break the main correlation between CNY and very bad global results, it seemed worth the trouble. Pawning off some proportion of their dollar difficulties on to the pristine reputation and condition of Hong Kong banks was, I have to say, pretty impressive. |

Hong Kong HKD, Jul 2012 - Jan 2018 |

| But have they now taken it too far?

I can easily understand why they might have. After all, the Chinese are stuck with the eurodollar system and having exhausted every conventional, textbook answer (leaving them to create enormous debt and leverage, and for what?) they didn’t have a whole lot of other options. It seemed almost logical that if they could “borrow” Hong Kong to reduce the hit to CNY, why not go “all in” and use the city’s facilities to put CNY in total reverse? The trouble with such a maneuver is that in one very important sense the PBOC has become the Bank of Japan. What I mean by that is they are now totally out there in full view, active in a big way which can have the effect of confirming that there is, in fact, still a big problem with China, CNY, and most especially “dollars.” They are no longer in the background, lurking through ambiguity. |

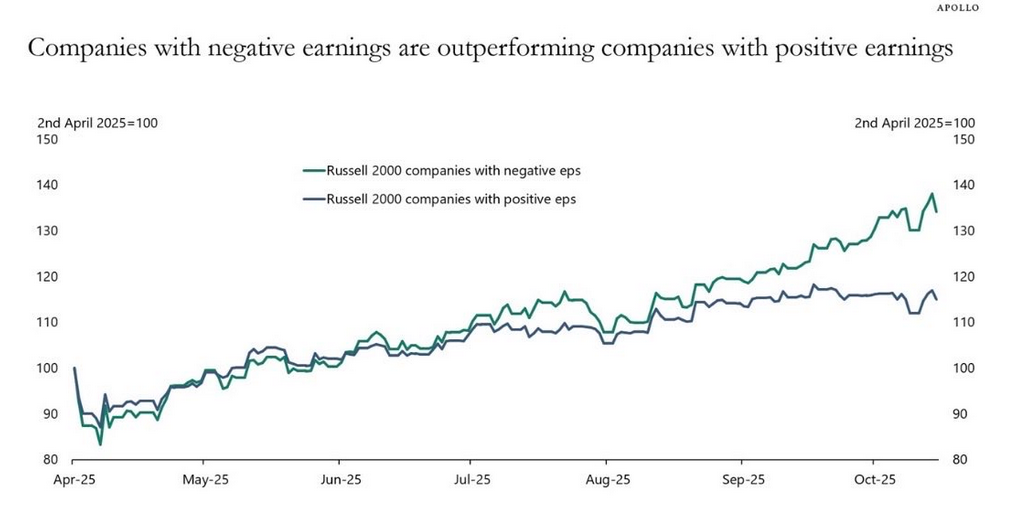

All China's "Dollars", Aug 2016 - Jan 2018 |

The one caveat to this obvious relationship is the Western media. They have done such a poor job describing the situation that it actually works to the PBOC’s benefit. It’s all right there in front of anyone who might look, but nobody cares to because the media is fully invested in its ignorance (very much like August 2015 through January 2016). At least for now.

There may come a time, however, when like January 2016 even the most recalcitrant optimist may no longer be able to deny the PBOC’s efforts. And once that happens, what’s at stake is the wider realization about what that clear presence might actually mean, and signal. If they have taken such extreme measures as this, and have been doing so for more than a year, what is the true state of things? What broader, more meaningful risks does that suggest?

Central banks have put themselves into this position for one reason – incompetence. In the West, institutions like the Federal Reserve are dedicated to transparency not really because it helps monetary policy but more so because it might in the end offer an excuse for, or way out of, some very hard questions. We know we failed because we don’t know what we are doing, but we’ve tried very hard to be quite open about it the whole time!

China’s position is far simpler; they long ago made a deal with the devil, the eurodollar devil. Theirs is not ineptitude so much as the bill for that trade finally coming due. They’ve tried to pay up in private, but Beelzebub always demands for the world to know who’s really running things.

Tags: $CNY,$JPY,Alan Greenspan,Bank of Japan,China,currencies,economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,hkd,Hong Kong,Markets,Monetary Policy,newslettersent,PBOC,rising dollar,Transparency