|

We tend to measure what’s easily measured (and supports the status quo) and ignore what isn’t easily measured (and calls the status quo into question).

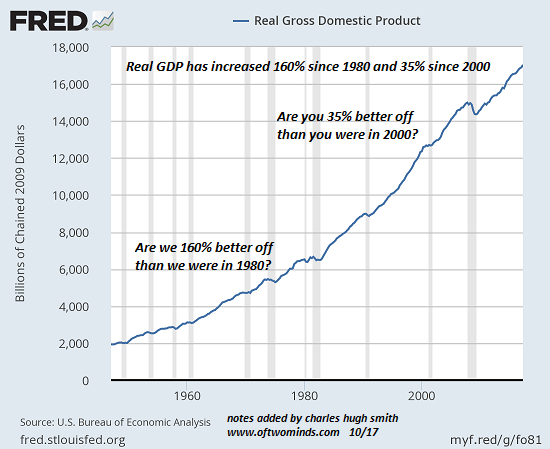

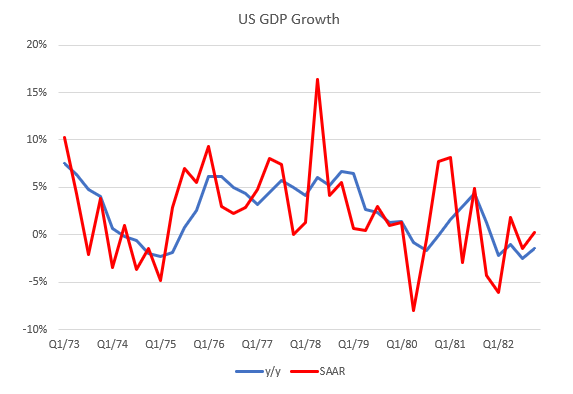

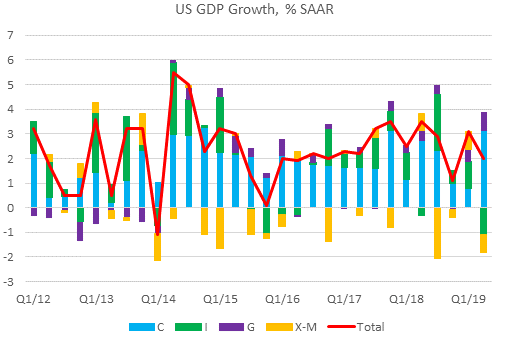

If we use gross domestic product (GDP) as a broad measure of prosperity, we are 160% better off than we were in 1980 and 35% better off than we were in 2000. Other common metrics such as per capita (per person) income and total household wealth reflect similarly hefty gains.

But are we really 35% better off than we were 17 years ago, or 160% better off than we were 37 years ago? Or do these statistics mask a pervasive erosion in our well-being? As I explained in my book Why Our Status Quo Failed and Is Beyond Reform, we optimize what we measure, meaning that once a metric and benchmark have been selected as meaningful, we strive to manage that metric to get the desired result.

Optimizing what we measure has all sorts of perverse consequences. If we define “winning the war” by counting dead bodies, then the dead bodies pile up like cordwood. If we define “health” as low cholesterol levels, then we pass statins out like candy. If test scores define “a good education,” then we teach to the tests.

|

US Gross Domestic Product, 1960 - 2017(see more posts on U.S. Gross Domestic Product, ) |

We tend to measure what’s easily measured (and supports the status quo) and ignore what isn’t easily measured (and calls the status quo into question). So we measure GDP, household wealth, median incomes, longevity, the number of students graduating with college diplomas, and so on, because all of these metrics are straightforward.

We don’t measure well-being, our sense of security, our faith in a better future (i.e. hope), experiential knowledge that’s relevant to adapting to fast-changing circumstances, the social cohesion of our communities and similar difficult-to-quantify relationships.

Relationships, well-being and internal states of awareness are not units of measurement. While GDP has soared since 1980, many people feel that life has become much worse, not much better: many people feel less financially secure, more pressured at work, more stressed by not-enough-time-in-the-day, less healthy and less wealthy, regardless of their dollar-denominated “wealth.”

Many people recall that a single paycheck could support an entire household in 1980, something that is no longer true for all but the most highly paid workers who also live in locales with a modest cost of living.

As noted in yesterday’s post, About Those “Hedonic Adjustments” to Inflation: Ignoring the Systemic Decline in Quality, Utility, Durability and Service, the quality of our products and services has declined dramatically, even as prices continue marching higher.

Meanwhile, inequality and officially protected privilege has soared, as I outline in my book Inequality and the Collapse of Privilege.

The gulf between these two narratives–the ever-higher financial statistics, and our unsettling sense that we’re less secure, less healthy and less wealthy–is widening. I think the Grand Canyon is an accurate metaphor here: the mainstream media parrots glowing official statistics on the distant side of the canyon, while on the lived-in-world side, well-being continues decaying.

Full story here

Are you the author?

Previous post

See more for

Next post

Tags: newslettersent,U.S. Gross Domestic Product