Unanimity SyndromeIf there is one thing apparently no-one believes to be possible, it is a resurgence of consumer price inflation. Actually, we are not expecting it to happen either. If one compares various “inflation” data published by the government, it seems clear that the recent surge in headline inflation was largely an effect of the rally in oil prices from their early 2016 low. Since the rally in oil prices has stalled and may well be about to reverse, there seems to be no obvious reason to expect the increase in CPI to continue, or heaven forbid, to accelerate. |

|

| So-called “inflation expectations” – which really means expectations about the future rate of change of CPI – have certainly risen following the US election, in expectation of a Trumpian spending spree and the possibility that higher tariffs might be imposed. This is to say, they have surged in terms of certain market indicators, such as inflation breakevens and forwards. Moreover, bond yields have certainly risen as well – as we expected them to do, since oil price-related base effects were bound to boost CPI (as we mentioned several times in these pages).

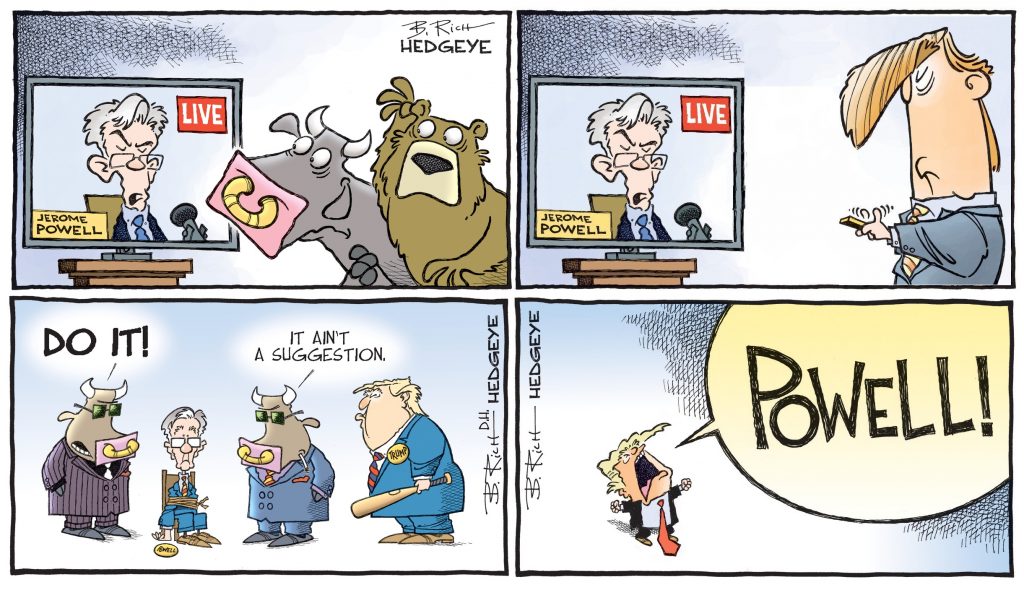

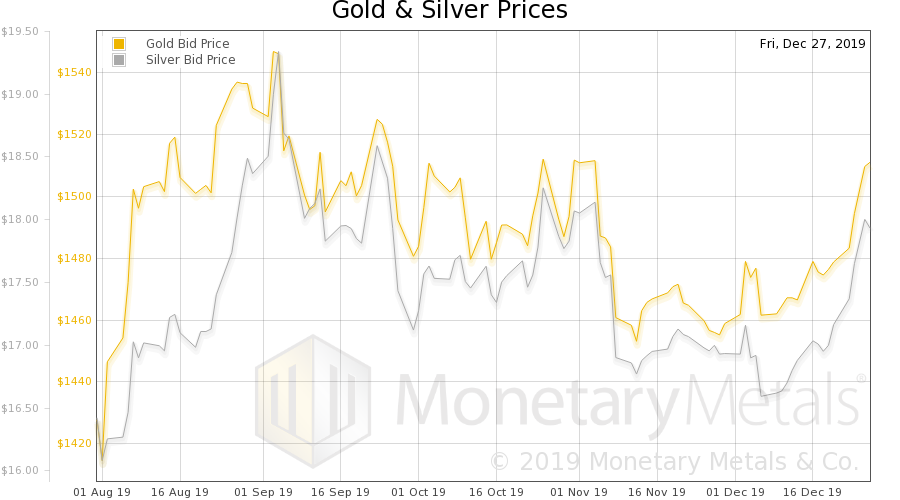

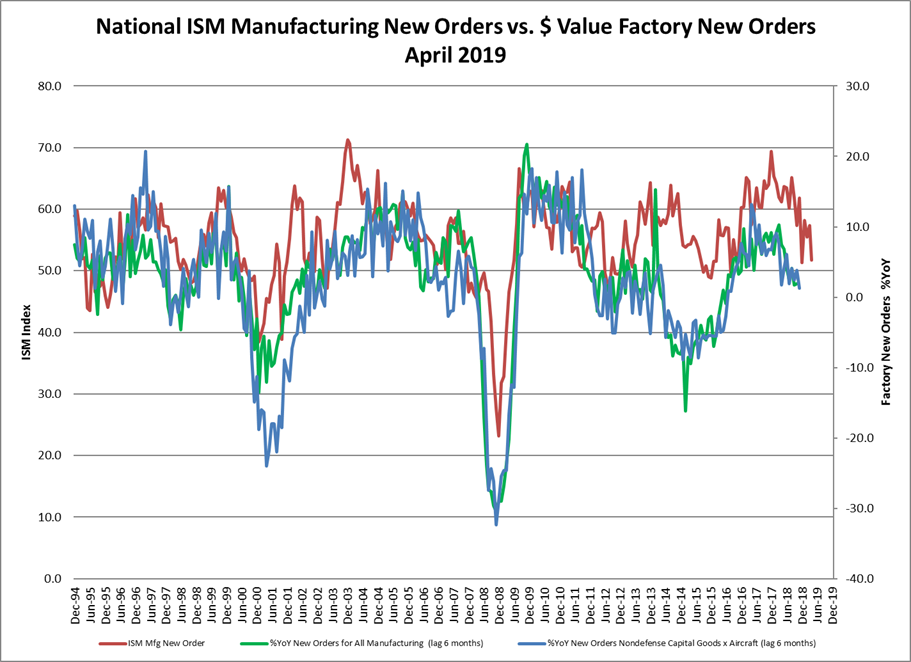

However, that obviously doesn’t mean that anyone believes rising consumer price inflation to represent a great threat, least of all an imminent one. This was brought home to us again shortly after the recent Fed rate hike, when a friend mailed us the following chart which was recently published at Zerohedge. It depicts the public’s medium term inflation expectations according to a regular consumer survey conducted by the University of Michigan. Ponder it carefully (the chart annotations are by ZH): As we looked at this chart, we were struck by two thoughts. For one thing, it dawned on us that the public’s expectations are probably not too far from our own and those of virtually everyone we know or are in contact with. These views are not necessarily similarly extreme, but no-one thinks there is going to be a big “inflation problem” anytime soon. For another thing, we began to wonder about the annotation added to the chart: if the chart depicts a “deflationary mindset”, the implication seems to be that prices should be expected to decline because of it. But if that is the case, one has to ask: What did this chart tell us in 1980? From there it is only a small step to the realization that expecting such an “inflation problem” to develop is currently the ultimate contrarian stance. Clearly that doesn’t necessarily mean that it will actually happen, or that it will happen soon. But we have learned over the years that if a certain event or trend in the markets or the economy appears to be completely impossible to nearly everyone, it sometimes becomes the “new normal” within a few years. As an illustrative example, think back to the situation in gold and commodities in the late 1990s. Who thought they could possibly make a comeback? We still remember the doubts people had that gold could remain above $300; or rise above $500 (the 1987 high); or rally above $850, and so forth. Even gold bulls were continually surprised. When the CRB index began to surge – before it became “common wisdom” that Chinese demand was going to drive it infinitely higher forever and ever – most discussions revolved around the imminent demise of the rally. The recent surge in CPI is eerily reminiscent of that situation. Fed officials certainly don’t expect it to be anything but temporary. No mainstream analyst considers it a potential threat. We cannot really find a good reason why it should happen either. Of course, as we e.g. mentioned almost two years ago in “Ms. Yellen and Inflation” and on a few other occasions, the long-standing distortions of relative prices in the economy on account of monetary pumping are bound to eventually reverse. |

Inflation Expectations, 1980 - 2019 |

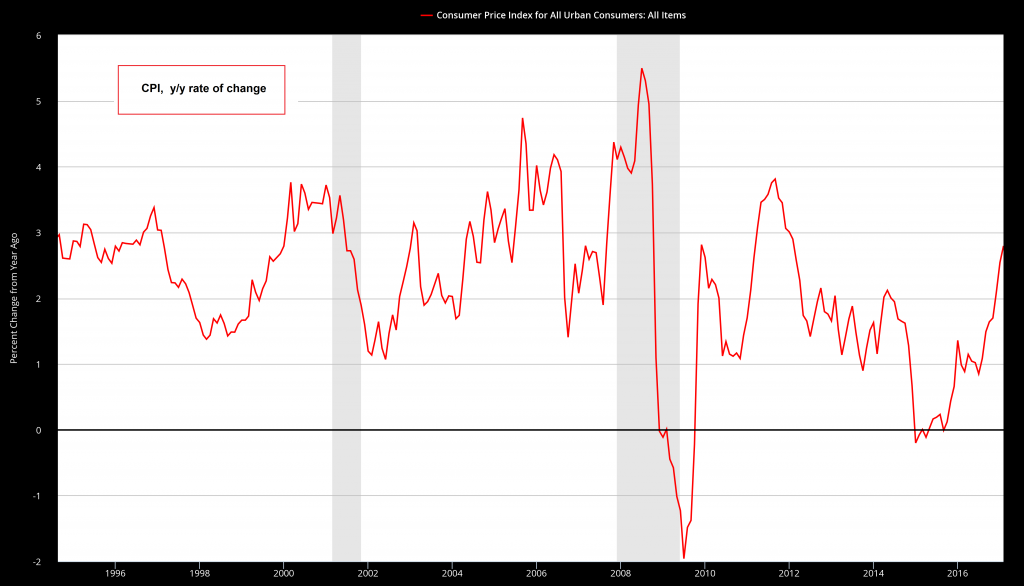

What Inflation Really IsWe often talk about monetary inflation in these pages, as that is what inflation actually is. When economists began to refer to rising consumer goods prices as “inflation”, they confused one of the possible symptoms of inflation with the phenomenon as such. Today the public thinks of this chart when it hears the term inflation: |

Consumer Price Index, February 2017 |

As Ludwig von Mises remarked, this Orwellian shift in terminology was by no means harmless:

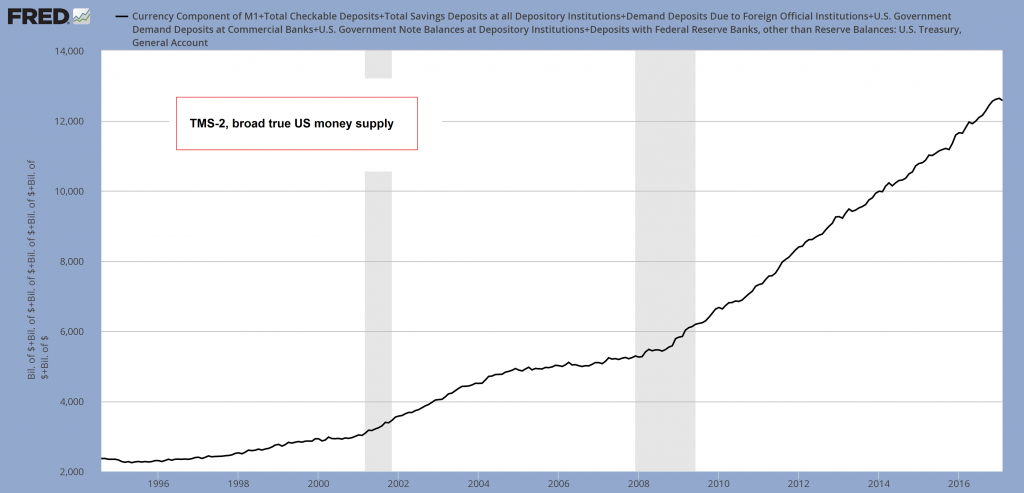

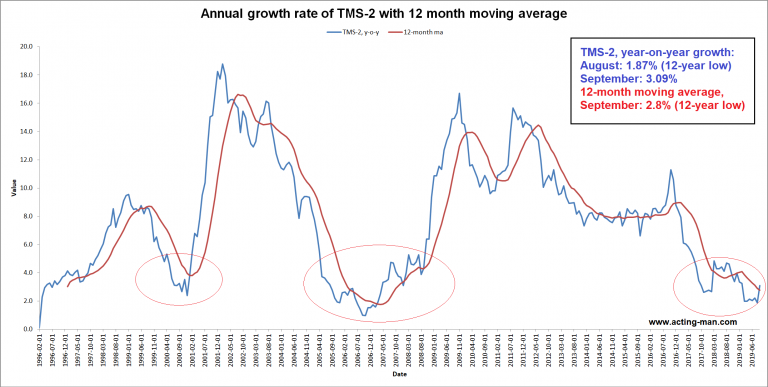

(emphasis added) Ain’t that the truth. Here is a chart of the broad US money supply TMS-2, the “true” money supply: As we always stress, consumer price inflation is just one possible symptom of monetary inflation and not necessarily the most pernicious one. The distortion of relative prices engendered by monetary inflation and the associated falsification of economic calculation that leads invariably to over-consumption and malinvestment of scarce capital is of greater moment in our opinion. After all, this is what creates the business cycle, i.e., the boom-bust phenomenon. It should be clear though that while an expansion of the money supply does not necessarily lead to a noteworthy rise in all prices (whether that happens depends not only on the supply of money, but also on the demand for money and the supply of and demand for goods and services), inflation of the money supply is a sine qua non precondition for an outbreak of “price inflation”. In other words, the policies reflected in the above chart have have definitely put the needed preconditions for an “inflation problem” into place. We leave you with what Mises said about those who pretend to fight inflation by tackling its symptoms (evidently, he did not put much stock in the ability of central bankers to even comprehend the situation they are tasked with handling):

|

Monetary Inflation, 1996 - 2016 |

Conclusion

Perhaps it would not be the worst idea to at least place a side bet on a resurgence of price inflation. One should definitely give some thought to one’s response, if seemingly against all odds, it actually does happen.

Charts by: Zerohedge, St. Louis Federal Reserve Research

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: newslettersent,On Economy