Summary:

Many see Yellen and Fischer at odds over benefits of high pressure economy.

However, this fails to put the comments in the proper context–same message different styles.

They are arguing against the doves who don’t want to hike this year.

Many observers are puzzled. The last FOMC meeting showed three regional presidents felt sufficiently convinced of the need to hike rates immediately that they chose to dissent.

Many observers are puzzled. The last FOMC meeting showed three regional presidents felt sufficiently convinced of the need to hike rates immediately that they chose to dissent.

On the other hand, the dot plots showed three officials did not think a hike this year is warranted. There is some speculation that one or two of these dots belonged Federal Reserve Governors (Brainard and/or Tarullo). The perception is that a Governor dissent is less common and is more significant than dissent from a regional Fed President.

The Fed’s leadership faced a dilemma in September, and this dilemma has been expressed a “close call.” Essentially, the choice was between which set of dissents are more acceptable. In this narrative, Yellen chose to face the regional President’s dissents, and we suspect allowed for a higher number of dissents to also underscore the knife-edge decision.

Nevertheless, the arguments of those who do not think a hike is appropriate this year, especially if they have been articulated by Governors, need to be addressed. It is in this context that Yellen and Fischer’s recent comments need to be understood. In their own ways, they both argued against the arguments that suggested to wait for inflation to be at the target before raising rates or raising the inflation target.

Yellen, showing respect for the other argument, said last week that it is plausible (meaning arguably by reasonable people) that holding the rates lower for longer will help further the recovery. The loss of aggregate demand reduced economic capacity. Letting the economy run hotter may help ease the supply-side restraints. This is apparently where many lost interest. Yellen went on to talk about the risks of what she called a “high-pressure economy.”

Fischer, in his own style, picked up on this sentiment yesterday. His comments were more pointed than Yellen’s which is why some observers see it as divergent. As the elder statesman, he cautioned against such ideas as waiting until inflation rises to or through its target before removing some accommodation. He says it would be too late. Monetary policy impacts with a lag.

Fischer also argued against changing targets (inflation and/or unemployment). He said that to do so undermines the entire framework. These, like Yellen’s, are not academic musings and ad hoccomments. They are arguments against some of their colleagues. It is done most respectfully, but it is an argument nonetheless.

We have been told that Yellen may have personally requested that Fischer, who served on the dissertation committees of both Bernanke and Draghi be her Vice-Chairman. She has a different relationship with him than say Tarullo, who she was reportedly previously not on speaking terms with for some time. There seems to be a deeply felt mutual respect between Yellen and Fischer, and it requires an unreasonable stretch of the imagination to think that he would take a difference of opinion with the Chair public. Fischer knows how he would want his assistant governor to act when he headed up the Israeli central bank.

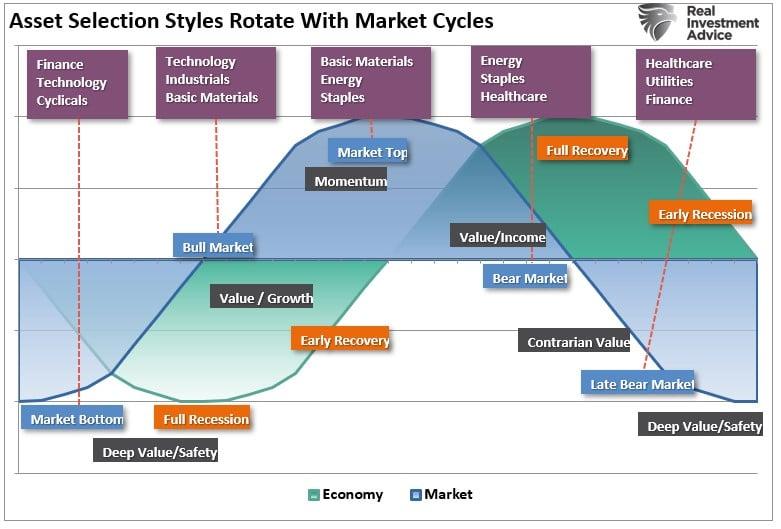

Lastly, we note that recent data has prompted many economists to lower their forecast for Q3 US GDP. The Atlanta Fed’s GDP tracker had begun the quarter anticipating more than 3% growth. As of last week, it has been gradually cut to 1.9%. With such slow growth, many questions why the Fed is still talking about hiking rates.

Our short response is two-fold. First, from a monetary policy point of view, the key issue is not absolute growth but the pace of growth about trend growth. For various reasons, trend growth has continued to slow. The Federal Reserve now estimates trend growth at 1.8%, and it may not be finished reducing it. It may, in fact, be closer to 1.5%. The US economy is growing near trend growth. Growth in absolute terms may seem low, but that is compared with earlier times which featured asset bubbles and superior demographics.

Second, as the former editor of the Economist noted recently, drawing on the work of the economic historian Angus Maddison, per capita incomes in what is now recognized as advanced industrial economies have risen on average 1.5%-2.0% a year for the last two hundred years. This suggests that maybe this is not simply the hangover after a debt crisis that Rogoff and Reinhart claim. Nor is it the secular stagnation that Summers champions. What we are experiencing is more typical, with the post-WWII recovery, baby-boom, and incorporation of large swathes of the world into the world economy generated abnormally strong growth for an abnormally long period.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: #USD,Demographics,Federal Reserve,Growth,newslettersent