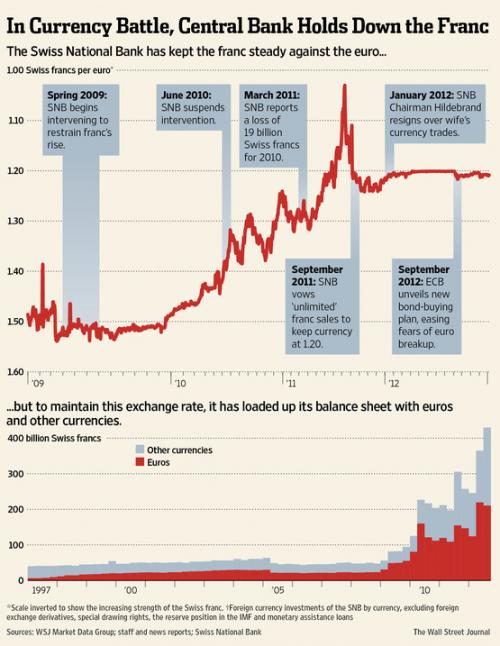

The high inflows of around 400 billion francs between 2009 and 2012 into the Swiss balance of payments could only be countered with an increase in reserve assets and interventions by the Swiss National Bank (SNB). This number is far higher than the one seen during the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, when the ten times bigger Germany had to buy reserves for 71 billion German Marks (at the time around 56 billion CHF). We look at the detailed history of these SNB interventions.

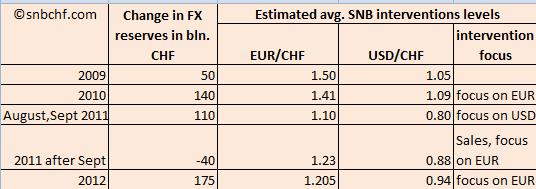

Overview:The following table gives a more detailed view of SNB purchases during the interventions: |

SNB interventions 2009-2012 |

Swiss Franc History: Financial Crisis and SNB Interventions until 2012

Until the financial crisis in 2008, FX traders’ and investors’ major concerns were nominal return and the global carry trade. Between 1999 and 2007 the Swiss saw heavy outflows from the financial account, in both portfolio and direct investments. This helped to offset the strong Swiss current account surplus.

After the financial crisis, however, the scenario completely changed. Instead of a nominal return in the carry trade period, investors now looked for safety, wealth preservation and real return.

Since the onset of the global financial crisis, the dynamics of Switzerland’s balance of payments have fundamentally changed. Instead of investing its large current account surpluses abroad via purchases of overseas assets, as it did habitually before the crisis, the Swiss private sector has been accumulating savings at home. …The resulting twin current and financial account surpluses have driven an unprecedented surge in the foreign exchange reserves held at the Swiss National Bank. (Source: Standard & Poor’s.)

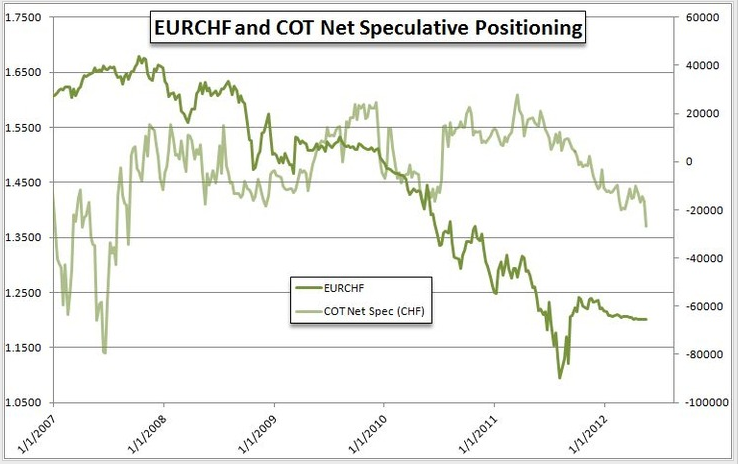

EUR/CHF and COT Net Speculative Positioning 2007-2012Standard & Poor’s is actually only partially correct. When they speak of “habitually before the crisis,” this mostly concerns the period between 1997 and 2007 when, thanks to the upcoming euro, yields and perceived risks in Europe decreased significantly. During the carry trade era until 2007, or the “great moderation” as Ben Bernanke, a bit misleadingly, named the period of excessive expansion of private debt, the franc strongly depreciated. Many used the CHF as the financing currency in carry trades. The following graph shows the carry trade between the euro and Swiss franc, visible in the COT Net Speculative Positioning. Until summer 2007, speculators were strongly short on the franc, with funds to be invested in high-yielding currencies, one of which was the euro. Still in 2007, speculators were short CHF with up to 40,000 contracts with a 100K CHF contract size each. Austrians and Eastern Europeans bought mortgages denominated in francs, which weakened the Swiss currency even further. Swiss companies kept their profits in foreign currencies. |

High inflows of around 400 billion francs between 2009 and 2012 in the Swiss balance of payments could only be countered with an increase in reserve assets and interventions by the Swiss National Bank. This number is far higher than the one seen during the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, when the ten times bigger Germany had to buy reserves for 71 billion German Marks (at the time around 56 billion CHF). We look at the detailed history of these interventions. - Click to enlarge |

|

With reverse carry trade flows, the EUR lost value again. The capital rushed back into Switzerland. This money boosted growth, the growth rate difference between Switzerland and the EU increased even more and Swiss property prices started their bubble run in 2009. The SNB had to absorb most of the funds and reinvest them in euros and dollars to keep the franc weak.

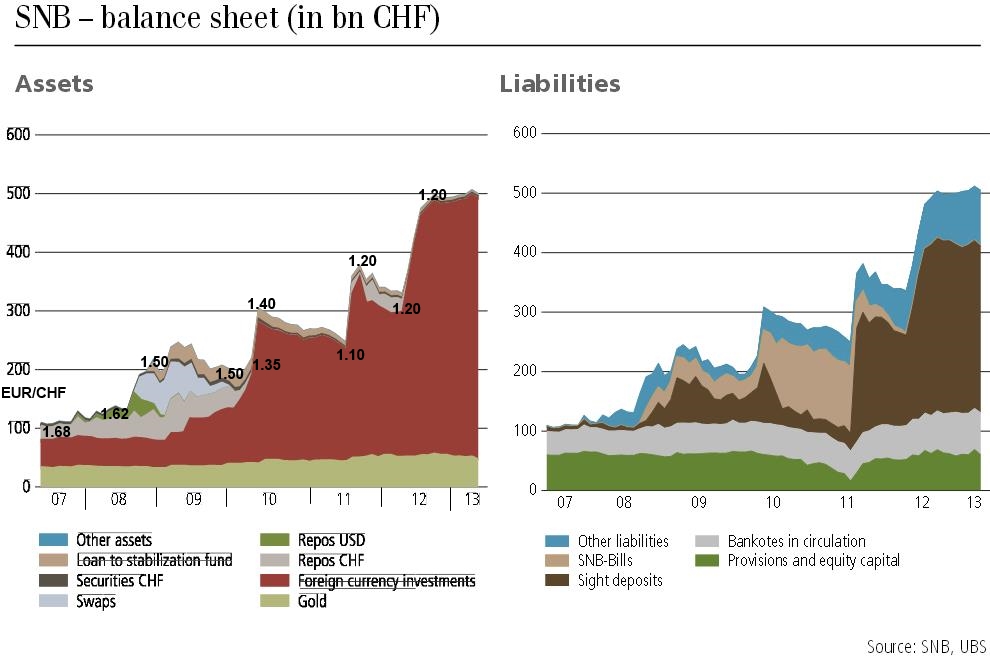

The following graph gives a high level overview of the SNB interventions =>

|

High inflows of around 400 billion francs between 2009 and 2012 in the Swiss balance of payments could only be countered with an increase in reserve assets and interventions by the Swiss National Bank. This number is far higher than the one seen during the collapse of the Bretton Woods system, when the ten times bigger Germany had to buy reserves for 71 billion German Marks (at the time around 56 billion CHF). We look at the detailed history of these interventions. - Click to enlarge |

2008: First intervention phase: Weak dollar, dollar repurchase agreements

|

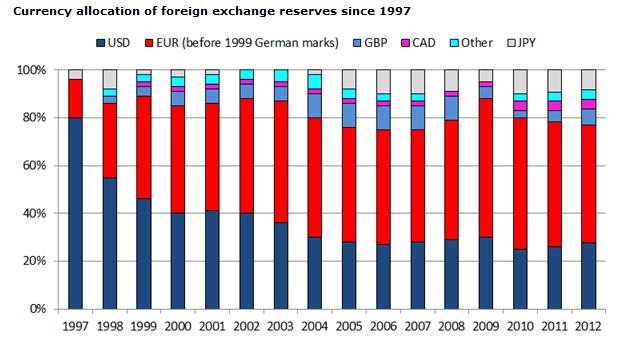

SNB Currency Allocation since 1997 SNB Currency Allocation since 1997. Source snb.ch |

2008/2009: Second intervention phase: Swap agreementsWith the outbreak of the financial crisis in September 2008, many foreign banks had CHF liquidity shortages, in particularly those that had previously borrowed in francs. The SNB introduced swap agreements with different central banks, a measure that eased the tensions. Despite gains on the swaps and on dollar repos, the SNB had losses of 4.7 bln. CHF in 2008, because the EUR/CHF fell from 1.60 to around 1.50. |

SNB Assets vs. Liabilities source UBS with EUR/CHF FX rate |

2009: Third intervention phase: The EUR/CHF 1.50 “line in sand”

In 2008 and 2009 Switzerland had 1.5% stronger GDP growth than the euro zone, but the SNB continued to claim that the “fair value” of the EUR/CHF was 1.50, the so-called “line in the sand.” and intervened regularly in the market to prevent “deflation risks” (examples in March, June and July).

Thanks to 7.3 bln. francs gained from gold and FX interventions at the line in the sand, the central bank managed to achieve positive results of 9.9 bln. CHF in 2009.

Cheap oil, QE1 and massive Chinese fiscal intervention led to a first timid global recovery. The SNB managed to reduce its balance sheet, closing most swap agreements, but sight deposits and FX investments increased by 50 bln. francs.

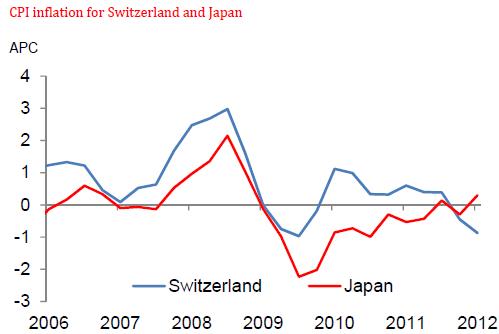

2010: Fourth intervention phase: The euro crisis startsIn December 2009, however, the euro declined against all major currencies – including CHF: the new Greek government admitted that deficit and debt statistics had been falsified for many years. The SNB did not fight against the falling euro, in particular because Swiss inflation was rising again (see below). The 1.50 “line in the sand” broke. Between February and June 2010, the SNB increased FX reserves from 100 to 240 bln. CHF, buying euros between 1.40 and 1.45. The bank was subject to criticism in the Swiss media. Despite the falling import prices caused by the appreciating franc, Swiss inflation rose to over 1% in early 2010. The SNB had to obey its “price stability” mandate and left the franc to market forces. |

Inflation Rate Switzerland and Japan 2007-2012 |

June 2010 – July 2011: CHF is allowed to float freely

Between the end of June 2010 and July 2011, the franc was allowed to float freely. The EUR/CHF exchange rate moved from 1.40 down to nearly parity. During this CHF appreciation period, the SNB was able to sell reserves of around 50 bln. CHF. At the same time it issued SNB bills to sterilize sight deposits.

The fall of the EUR/CHF to the book value of 1.24 and USD to 0.94 resulted in losses of 20 billion CHF in the 2010 balance sheet. Even more than before, the central bank was subject to critical voices from the media, especially from the right-wing People’s Party (SVP).

Overshooting in summer 2011 and establishment of a floorIn spring 2011 the carry trade reappeared, this time against the yen. As opposed to the time before 2007, the franc was now an investment currency for the carry trade, fueled by demands that the SNB should hike rates. The CHF/JPY rose by 10% from 85 to 93. Still in June 2011, most investors thought that the SNB would hike rates soon based on the SNB’s own inflation expectations of 1% in 2011-2012 and 1.7% in 2013. In summer 2011, global growth slowed more and more, and the Euro zone problems intensified. Germany and Switzerland continued to outpace the U.S. and the rest of the euro zone. Thanks to rising inflation and a very risk-adverse investment climate, the Swissie continued its rise despite an interest rate differential of 2% in favor of the ECB. The CHF/JPY carry trade reached 107. At the beginning of August, the SNB decided to intervene and bought back the SNB bills it had issued previously. Finally, it even increased the monetary base – sight deposits and CHF cash – in order to buy even more reserves. |

On August 9, the Fed held its FOMC meeting and hinted at a form of monetary easing. On one single day, the EUR/CHF rate touched an intraday low of 1.0083, but saw a high of 1.0841 and close of 1.0381. In a later FOMC meeting, this easing was detailed and called Operation Twist.

The SNB increased its FX investments by 110 billion francs; concentrating purchases more on the weak U.S. dollar, but also on German government bonds. Given the gloomy global economic forecasts, one thing was clear: this time the franc overshot. Still, the question remained of what the fair value was. For the SNB it was 1.20. On September 6, the bank established a floor, a minimum rate of 1.20 of EUR/CHF, and claimed it would do “unlimited” Forex purchases at this level. FX traders followed the bank quickly, in minutes the rate rose from 1.10 to 1.20.

2012: EUR/CHF becomes a peg and not a floor

With market speculation that the SNB could raise the floor to 1.25, the bank was able to reduce reserves by the equivalent of 40 billion francs until March 2012. The fact that the SNB itself sold foreign currency and drove down the EUR/CHF to 1.20 confirmed the view that 1.20 was a peg and not a floor. The author made this visible to a broader audience on Zerohedge with “Guest Post: SNB Buys Swiss Francs And Sells Euro: Welcome To The EUR/CHF Peg“.

In May 2012 the euro crisis intensified again, and growth in the U.S. was still limited. The market had understood that the SNB would not further raise the floor. As a consequence, the SNB was obliged to purchase FX reserves for the equivalent of 175 bln. francs in only four months between May and August 2012.

Comments on minimum exchange rate

The floor of 1.20 is strong in many aspects:

- It was nearly 20% above the overshooting level of 1.0083 EUR/CHF. Later, the exchange rate remained mostly under 1.23. Therefore, 1.20 does not really represent a “floor”, but rather a “peg”.

- The SNB did not follow the basic principle of currency intervention, established by Milton Friedman: buy at the lowest points, but not at a level that is 20% higher. This leads to excessive monetary easing. The floor established against the German Mark in 1978 led to high monetary expansion and 6% Swiss inflation some years later. Therefore, it was deeply regretted by former SNB chairman Leutwiler.

- The floor only considered the EUR/CHF exchange, whereas the dollar could revalue against the franc without limits. A strong revaluation of the dollar (and the related Yuan) would make Swiss international companies more competitive, which quickly happened.

- “Deflationary pressures” were mostly driven by the strong franc. However, prices of services and goods produced in Switzerland only fell slightly in 2011/2012 and were rising again in 2013. Between 2009 and 2014, Swiss wages increased steadily between 0.5% and 1% per year and real estate prices improved far more. This is not a deflationary spiral.

Over the long-term, wages determine inflation rates and not FX rate fluctuations. Abenomics is trying the push up Japanese yearly wage hikes from initially negative values using massive currency depreciation. This is not needed in Switzerland because wages rise more quickly there. - The Swiss franc is for many still a safe-haven, similar to gold, that can preserve – but not augment their wealth. 60% of all CHF issued bank notes are those with a value of 1000 CHF.

- Once inflation approaches 1% the SNB might need to imitate Singapore and implement a managed currency appreciation.

The floor of 1.20 seems to be a longer-term target, valid at least for two or three years, or like Jordan said “it is maintained as long as it is no longer necessary”. Thanks to the floor, Swiss companies are able to base their business calculations again on a solid basis.

With the retreat of former hedge fund manager Hildebrand, who risked and lost his jobs doing insider trading, the remaining SNB council members are mostly academics and rather typical “Swiss”. A typical Swiss has a character attitude that prefers to avoid risk: visible especially in the delivery by Swiss law of secret banking data to the United States.

The Swiss mentality seeks compromises with the market (or the U.S. government) instead of challenging it. After markets drove the EUR/CHF down to parity, a chairman different from Hildebrand might have set the floor to 1.10 and not 1.20.

We think that the early interventions in 2009 and 2010 might have come from Hildebrand, even if Jordan later provided the needed theoretical framework. On the other side, Hildebrand was still a hawk to counter the Swiss real estate bubble, only three months before the floor introduction!

Having advocated the expansion of the Swiss monetary base in 2003, already in 2005 he was in favor of rate hikes, earlier than the other members of the SNB council.

In summary, Hildebrand seemed to be a rather interventionist central banker. But the history of the SNB and Swiss mentality showed that strong monetary easing was only done in extreme cases. An example is the overshooting of the franc exchange rate combined with a bad perspective for the world economy. That happened in 1978 and in September 2011.

<– Back to CHF history overview

See more for