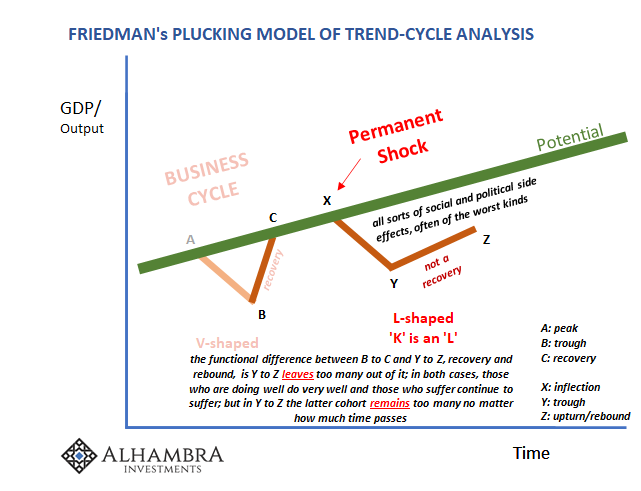

| We’re only ever given the two options: the economy is either in recession, or it isn’t. And if “not”, then we’re led to believe it must be in recovery if not outright booming already. These are what Economics says is the business cycle. A full absence of unit roots. No gray areas to explore the sudden arrival of only deeply unsatisfactory “booms.”

Every once in a while, however, even the mainstream media meanders closer to the actual economics (small “e”) of the real world. Sometimes the evidence simply overwhelms the ideologically enforced myths, leading honest inquiry to tremendous if unorthodox clarity. One of those cases was written up in The New York Times late in September 2018. If only to (correctly) bash Trump’s “boom”, still there was every reason to suspect before the man took the White House why his economic message centered appropriately around the fakeness of the faulty unemployment rate may have resonated in exactly those states which put the otherwise brash, abrasive New Yorker over the top of the 2016 election.

Three years too late, The Times came to a shocking conclusion:

|

|

|

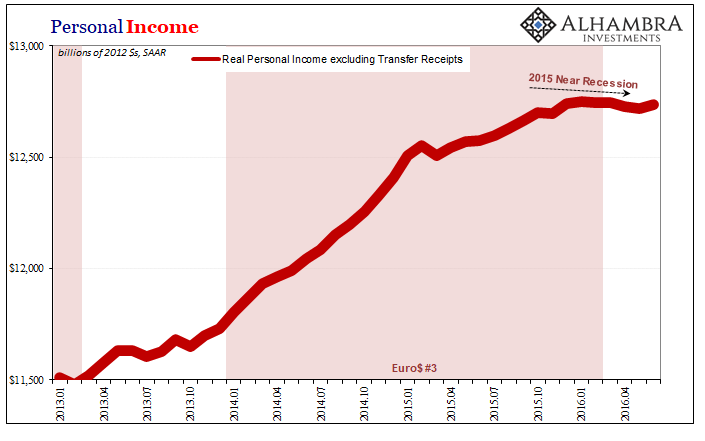

Interesting, too, how the headline for this specific article has been revised over the years; it started out with the title Invisible Recession of 2016 which today says The Most Important Least-Noticed Economic Event of the Decade (and the URL a strange mishmash of the two). Either way, for once they describe – in arrears – the very nature and essence (“run-up in the value of the dollar”) of Euro$ #3. It was only “a hard-to-explain confluence of forces” if you accept Economics; not just with regard to its version of the business cycle, but more so what we’re supposed to believe about central banks, dollars, and what we’ve been told happens with regard to how those impact the real economy. Having been writing about Euro$ #3 in real time as it unfolded, including tremendous dollar cautions all throughout 2013, before the blatant if also unorthodox eruptions in curves like the dollar’s exchange value in 2014, there were data series aplenty warning of impending real economy problems and deflationary potential. Including economic data prepared and published by the “central bank” itself. On the same day in December 2015 that Janet Yellen hiked the fed funds target for the first time, ostensibly signaling the FOMC’s confidence about recovery and eventual boom, the Fed also released a minus sign for its Industrial Production numbers which was consistent with instead recession. It was only a “silent recession” because the media never reported it; Americans like especially workers around the rest of the world suffered from the thing anyway.

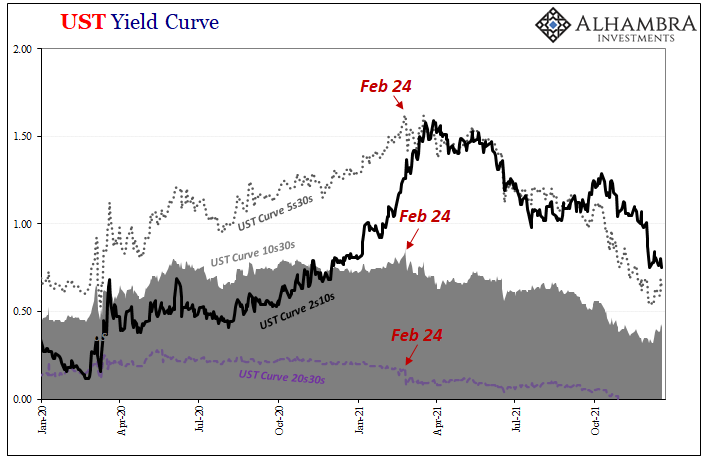

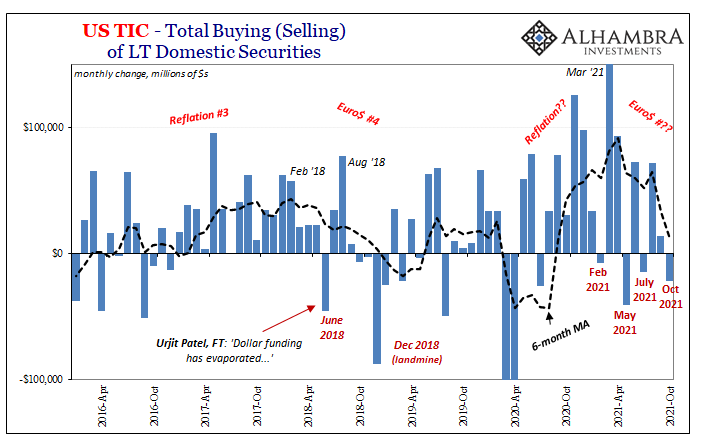

Yet, here we are in late 2021 in basically the same situation as both 2015 as well as September 2018 when the one single Times writer had perhaps accidentally discovered the vast distance in between “official” recession and an economic boom that never boomed; a recovery that didn’t lead to recovering. |

|

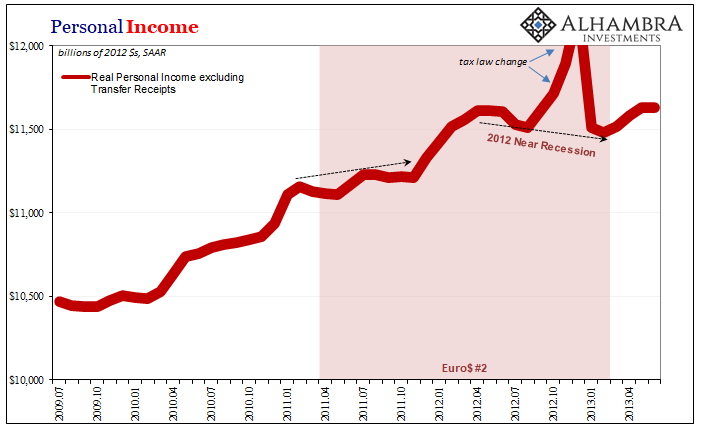

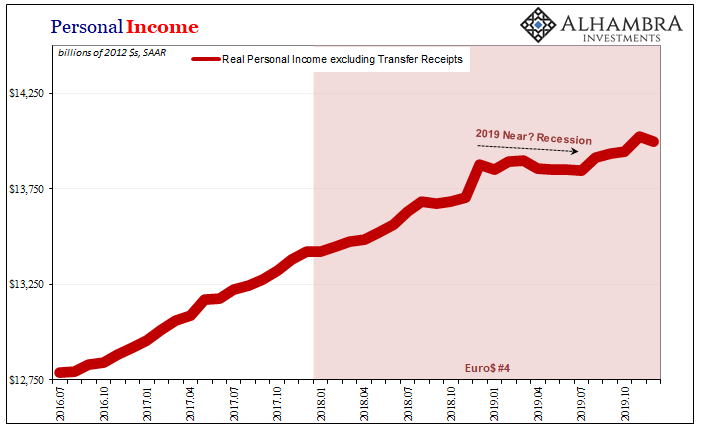

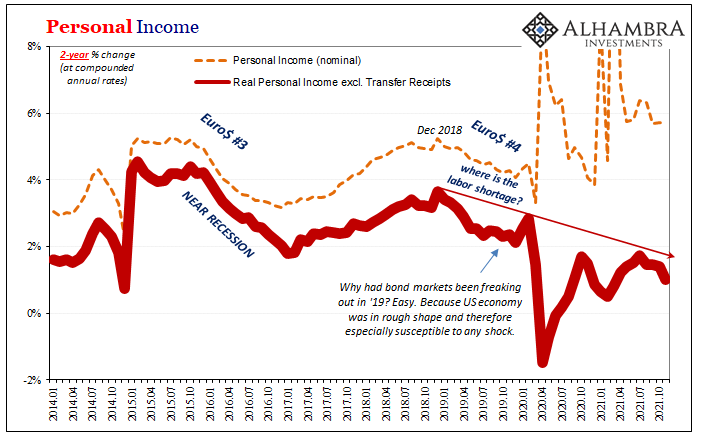

| Beside IP, there were others. The NBER itself uses four distinct economic accounts apart from real GDP to date the “official” business cycles, only beginning with Industrial Production. One other vital data point is the BEA’s Real Personal Income Excluding Transfer Receipts.

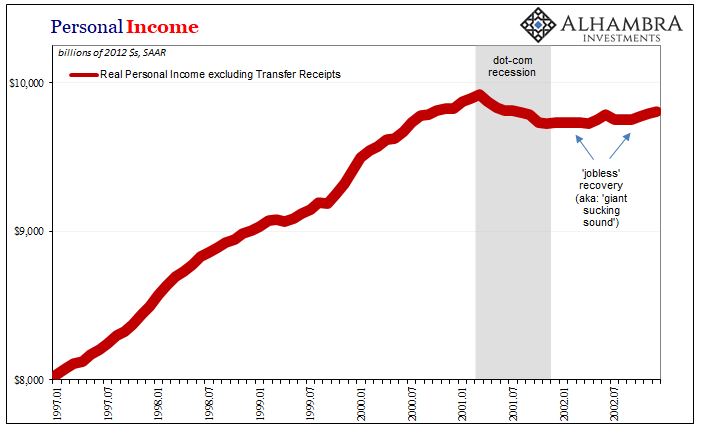

This one is as historically validated as IP, meaning that the NBER has recognized the close similarities and correlations between negative changes which show up in this broad measure of private economy income (thus, excluding transfers) and the near-certain tendency for real-world contraction. When Real Personal Income Excluding Transfer Receipts stumbles, you can be assured something big is not right. Whether what’s wrong is recession, this is a question you don’t want to leave to either the media or Economics. They’ve both already pre-answered with the either/or presented up top. Start with the year 2001; while even today the public gets that year’s recession mixed up with the events of September 11 (again, such a poor job of reporting on economics and economic history), the downturn itself clearly began half a year before them. Not only did this economic series peg the recession, it also gave up the aftermath which wasn’t recovery, at least not one straight away (therefore, to George W. Bush’s early campaign struggles over “his” “jobless recovery”). During the eighteen months immediately following the trough, the economy was neither in recession nor legitimately recovering. And this is why Alan Greenspan’s Fed was still cutting rates instead of hiking them as had been projected all the way until June 2003, almost two years after the recession had been declared over (by the NBER). Fortunately for at least Mr. |

|

| Bush, the recovery would show up during the second half of 2003 to save his 2004 reelection.

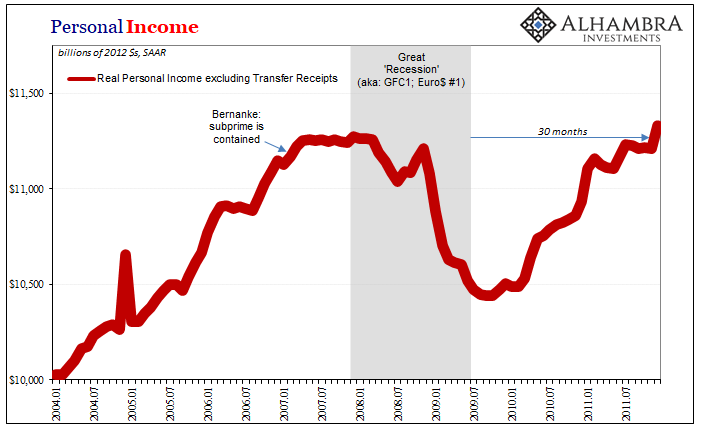

The man Bush tapped to replace outgoing Alan Greenspan at the Fed, Ben Bernanke, he would follow no such fortune – to which the entire world would pay a huge price. The very next month after Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke would tell Congress in March 2007 subprime was contained, in addition to the plethora of contrary curve and market signals, again Real Personal Income excluding Transfer Receipts declared him a fool (to be fair, the data has been revised many times over time though the original series wasn’t actually that far off from the updated pattern). |

|

| Not only that, once more the same data picture a sluggish if not lack of recovery directly following the deep contraction contrary to every expectation of Economics’ business cycle theory (symmetry; the deeper the drop to the trough, the faster and more forceful the recovery should have been).

Part of this non-boom to the decade-long “recovery” effort had to do with all the things it took until September 2018 for The New York Times to notice: “sharp slowdown in business investment, caused by an interrelated weakening in emerging markets, a drop in the price of oil and other commodities, and a run-up in the value of the dollar.” In short, the eurodollar cycles which aren’t the same as the mainstream’s theory about the business cycle. Yet, even the data, like the market indications, is consistent including the powerful message contained within this key BEA measure of private economy income. |

|

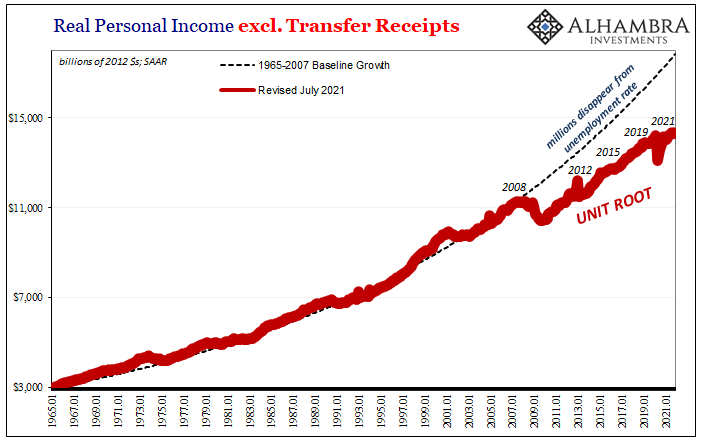

| The “silent” recession of 2016 (actually 2015) appears in it as had 2012’s like 2019’s would: | |

| Long story short, when you see this particular data point bend and then drop, even by a little, there’s nothing good going for the private economy regardless of the NBER’s citation or the financial press’s near-constant incurious position.

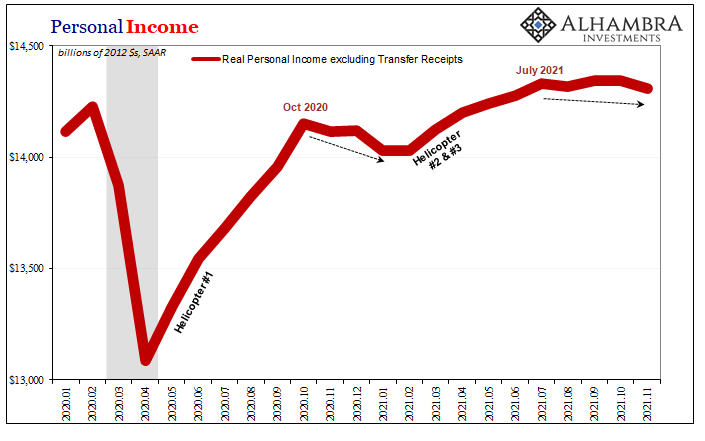

As you can probably already tell, all this to set up the latest data for, yes, Real Personal Income Excluding Transfer Receipts. Ugly: |

|

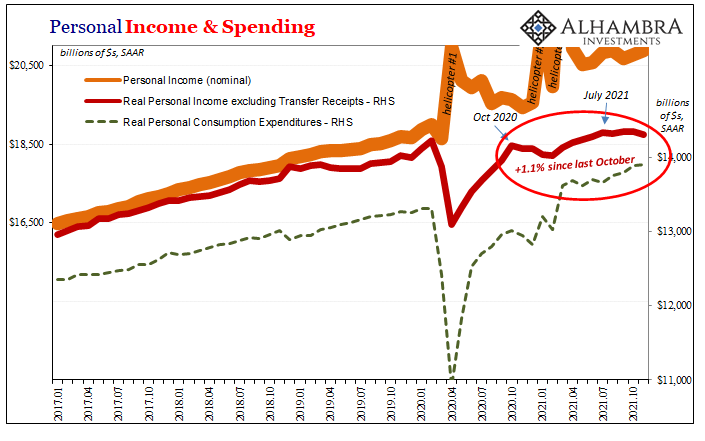

| Since July 2021, incomes have been falling in real terms because private economy income hasn’t been keeping up with price changes. In fact, income growth has been flat going all the way back to October 2020, an entirely too-long period for the system to be held back where it cannot afford it. As a result, the economic situation is, well, “growth scare” further into 2021 akin to the oil shock situation.

Americans, like their counterparts around the rest of the world, are falling further behind, here in the data represented by falling real incomes; the 2-year change for the data (above) is substantially less than at any time during any of the 2012, 2015, or 2019 near recessions. And, obviously, this takes account of the various massive helicopters Uncle Sam had blithely disbursed last year and the first part of this year. |

|

| While those may have created a true ripple of activity, and made the economy appear recovery-like – for a time – especially in terms of nominal incomes, it clearly did not lead to an actual recovery in a private economy more and more that seems instead particularly damaged if not deadened. | |

| There was no multiplier effect on the government “stimulus” (forget QE).

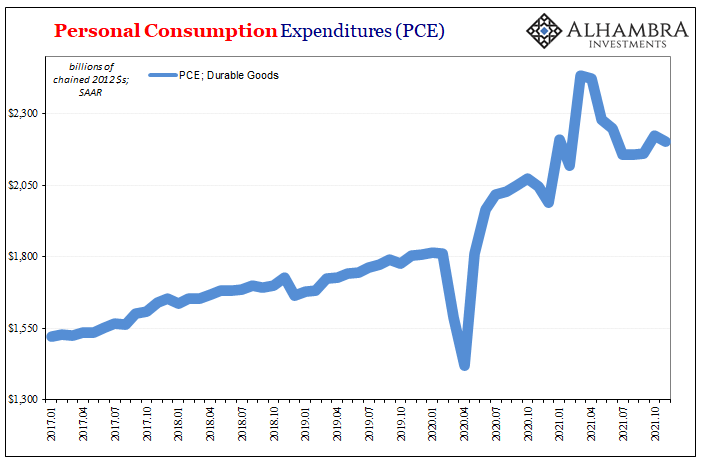

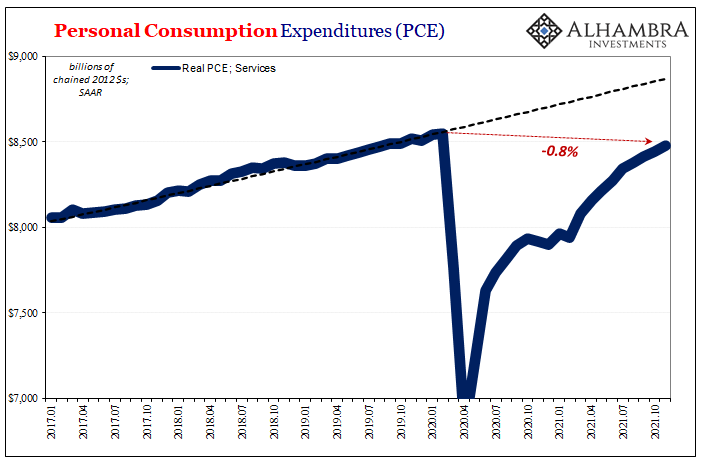

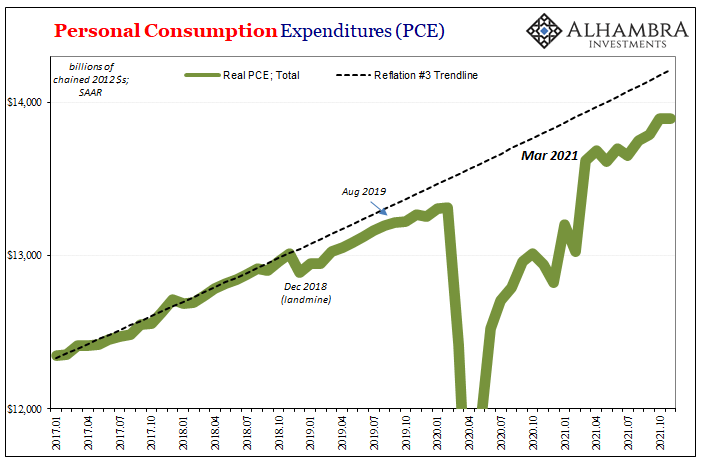

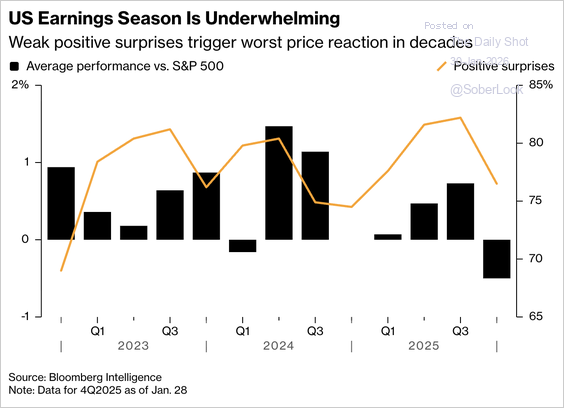

In fact, despite the helicopters and the obscene glare from “inflation” and the goods economy gone nuclear, even US consumer spending on the whole remains substantially behind the prior trend (which was a post-2008 not-booming trend) due to an impaired services sector which may never come back. What this data, like the markets, is telling us is that maybe, just maybe despite all the noise about consumer prices and consumers buying up durable goods transitorily, the 2020 “recession” was not papered over and filled in and up by the generous “donations” from Uncle Sam. |

|

| On the contrary, the more time passes and the further we get away from those, the more it seems the underlying private economy resembles the post-2008 economic moonscape.

While perhaps still a “growth scare”, it’s not really the same as what may be pictured from most if not all commentary; those declare this as a possible slowing down from a white-hot pace, when the actual thing by data and market is a global system reverting to a damaged mean after an all-too-fake bout of artificial activity. It’s hardly stagflation, it’s like 2010 all over again. |

|

| Why are interest rates so low despite double-taper and triple rate hikes? By all accounts (that matter) if it looks like a eurodollar cycle, it very likely is.

Economics is forcing everyone including the FOMC to make the same regrettable errors; from being unable to interpret data apart from anachronistic assumptions about the business cycle to stupidly dismissing these market signals, all to maintain economic silence about what’s really happening. Again. |

|

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,Business Cycle,currencies,dollar,economy,EuroDollar,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,industrial production,Markets,nber,New York Times,newsletter,PCE,Personal Income,real personal income excluding transfer receipts,recession