After years of futility, he was sure of the answer. The Bank of Japan had spent the better part of the roaring nineties fighting against itself as much as the bubble which had burst at the outset of the decade. Letting fiscal authorities rule the day, Japan’s central bank had largely sat back introducing what it said was stimulus in the form of lower and lower rates.

No, stupid, declared Milton Friedman. Lower rates don’t mean stimulus they mean monetary policy has been tight leaving the economy stripped and starved of this vital necessity. He had declared this a fallacy back in the sixties only to see it proven by the opposite direction (the Great Inflation was punctuated by skyrocketing interest rates, contrary to popular perception).

On April 30, 1998, the great monetarist’s diatribe was reprinted for the Hoover Institute. Though much of what modern central banks have done they did in his name, Friedman spared his Japanese disciples no venom. “A decade of inept monetary policy by the Bank of Japan deserves much of the blame for the current parlous state of the Japanese economy.”

Confusing their low rate policy with actual monetary accommodation, authorities had let the money supply dwindle; worse, they did so against the increasingly dramatic advice of the JGB market, the market for government bonds and therefore the risk-free guide for reading reality on the ground inside the real economy. Bond yields had been dropping no matter what fiscal spending splurge had been applied, a JGB rally all along being wrongly attributed to rate cuts that didn’t actually move the needle.

Initially, higher monetary growth would reduce short-term interest rates even further. As the economy revives, however, interest rates would start to rise. That is the standard pattern and explains why it is so misleading to judge monetary policy by interest rates. Low interest rates are generally a sign that money has been tight, as in Japan; high interest rates, that money has been easy.

Thus, the answer was the same one which had brought Milton Friedman and his co-author Anna Schwartz international acclaim in 1963. In their book A Monetary History, the key passage for the whole thing was this one, the entirety of the “great” in the Great Depression in a nutshell:

It was the necessity of reducing deposits by $14 in order to make $1 available for the public to hold as currency that made the loss of confidence in banks so disastrous. Here was the famous multiple expansion process of the banking system in vicious reverse. That phenomenon, too, explains how seemingly minor measures had such major effects. The provision of $400 million of additional high-powered money to meet the currency drain without a decline in bank reserves could have prevented a decline of nearly $6 billion in deposits.

The Bank of Japan in the nineties like the US Federal Reserve in the early thirties had taken its eye off the ball, believing too much in the fallacy of interest rates. Confused by them, thinking low rates meant loose money, they let these economies be strangled by their own incompetence.

The solution to these tight money problems, therefore, was “high-powered money.” Back to Friedman in 1998:

The answer is straightforward: The Bank of Japan can buy government bonds on the open market, paying for them with either currency or deposits at the Bank of Japan, what economists call high-powered money. Most of the proceeds will end up in commercial banks, adding to their reserves and enabling them to expand their liabilities by loans and open market purchases.

| What we call today quantitative easing. While it seemed a radical step at the time, Japan was in need of a revolutionary answer.

But then Friedman made an equally enormous blunder of his own, claiming, “There is no limit to the extent to which the Bank of Japan can increase the money supply if it wishes to do so.” While that was true in terms of technical definitions, what any Economist or monetary official might term base or high-powered money, that wasn’t true of the actual banking system and hadn’t been for a very, very long time already. Maybe it was old age or the fact that he hadn’t kept up on monetary evolution since he wrote A Monetary History. For whatever reason he, like Anna Schwartz in 2009, wrongly remained convinced that bank reserves were the effective trick, equaling high-powered money. Stuck in a 1960’s view of the 1930’s when the world had changed so much in between. |

|

| Even Alan Greenspan at the time knew there was no defining money in this fungible bank-centric system.

Regardless, the Bank of Japan eventually took up his suggestion. In March 2001, Governor Masaru Hayami announced the first modern QE. And it was immediately celebrated just as it was classified in exactly the way Friedman had earlier claimed. Here’s one contemporary example:

|

|

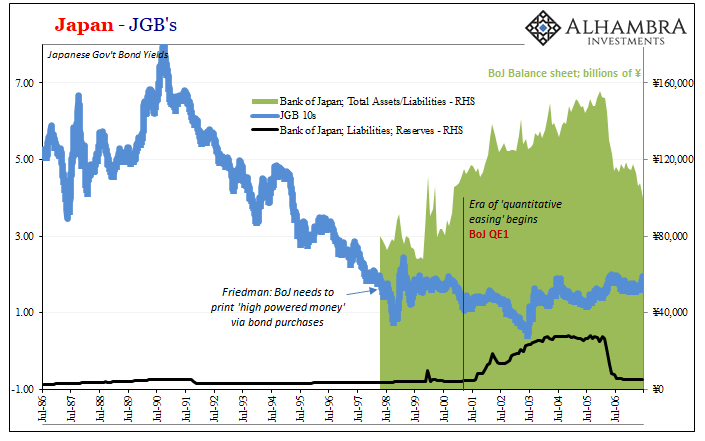

| The numbers grew massive, at least by the standards of the time. Like the US prior to 2008, there hadn’t been many bank reserves in the Japanese system especially after 1991. No more than around ¥3.5 to ¥4.0 trillion, give or take. |

Japan - JGB's 1986-2006 |

| By December 2001, however, bank reserves had bulged, rising to ¥10.8 trillion. Of course, as with all these things, QE1 was quickly followed by a QE2 to make these numbers even bigger. Always bigger numbers, the vain search for the magic right figure of bank reserves and balance sheet action.

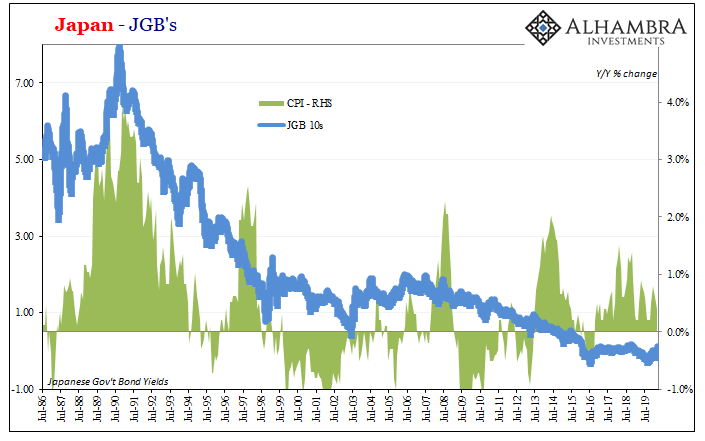

By the time the “money printing” leveled off around 2004, the systemic level of reserves had ballooned to more than ¥27 trillion, BoJ’s overall balance sheet shooting up to more than ¥150 trillion. The bond market, you’ll notice above, didn’t much buy the whole charade. The only reason yields hadn’t fallen farther was a global recovery emerging around the end of 2002 and the beginning of 2003. Inflation? Not much changed from the Lost Decade of the late nineties. |

Japan - JGB's 1986-2019 |

| There were some positive months for the CPI in 2004 and again in 2006, none large or sustained, which would go on to convince a second generation of BoJ QE’ers that maybe it had worked; the global recovery, yes, but in part perhaps this reserve stuff had helped. Just in time for the hand-off to Bernanke’s crew soon in the midst of their own monetary crisis.

Years earlier, though, even Economists at the San Francisco Fed spotted their error. It’s the one neither Milton Friedman would account for in 1998 nor Anna Schwartz blasting Ben Bernanke’s similar QE “money printing” explosion in 2009. Here’s what these researchers wrote in November 2001, while QE was still very new:

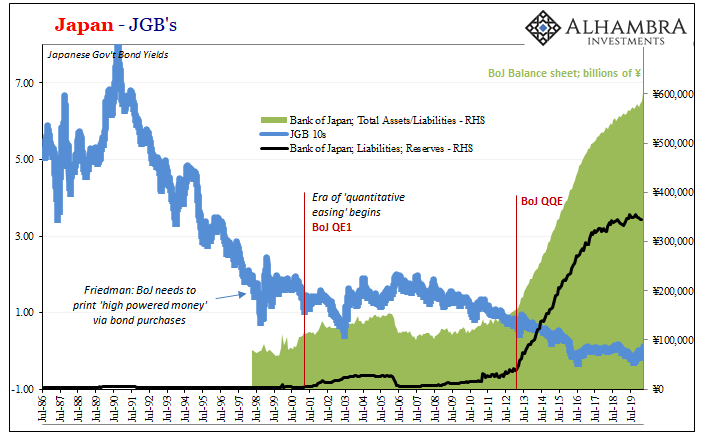

Is this a liquidity trap for the economy, or one which has captured monetary authorities unable to distinguish their own efforts from what banks find absolutely necessary? Bank reserves, like those in Japan and America, come off the “press” otherwise inert. It’s impossible to claim that banks are desperate for money but when you give some to them they refuse to do anything with it. The only conclusion you should draw, pace all the banks in the bond market, is that you haven’t given them money in the first place. All the world’s ongoing, seemingly intractable troubles in that one difference. So, Friedman was right about what was wrong, but then really wrong about what to do from there. The bond market in Japan merely agreed with both of those assessments – as it does still today. For one thing, the Bank of Japan has never ended its search for the magic number. If it wasn’t so tragic, you’d have to hand it to these officials for their doggedness; they just won’t give up no matter how many times this method comes up totally empty. QE doesn’t work? Make it bigger! That’s just what they did in 2013, a much, much larger balance sheet and reserve expansion befitting the extra “Q” which was appended to the prior abbreviation. QQE, in other words. |

Japan - JGB's 1986-2019 |

| And, my God, how it has accomplished just as little as the original. Inflation? Nope. Recovery? LOL.

Bond yields tell the story instead in all their gory details. These idiots have no idea what they are doing. But they won’t stop doing it. QQE, by the way, the most powerful monetary program ever conceived (until the next one) is today a month into its eighth year. This one fact alone tells you everything you’ll need to know about “money printing.” It’s not what you see that ultimately matters, especially if the sum total of what you see is only on the central bank’s balance sheet; a point which the San Francisco 2001 Research Note briefly attempted to investigate. Central bankers do something, maybe a lot of something, and they call this something “money printing.” Good for them. Don’t just take their word for it. The evidence is all over the place, just as it is all throughout history. If it was money printing, Japan wouldn’t be in this shape nor would America and the rest of the global economy. It’s not a liquidity trap, the Japanese pioneered the lack of liquidity trap which since August 2007 has gone global. |

The Real GDP Problem, 1988-2018 |

| They let the money supply dwindle in the early nineties, as Friedman had shown, but then did nothing about it while telling the world they were making huge increases. Only reserves. It hardened the banking system first and then the economy into this “deflationary mindset” for which Japan’s collective cabal of central bankers can’t pin down the right magic number of reserves and balance sheet expansion to finally withstand and overcome. They’ve had two decades.

And yet, the interest rate fallacy charges ever onward, the mainstream media totally complicit with their uniform stories describing money printing, stimulus, accommodation, and market support that doesn’t ever show up in reality. Oh, and all those warnings on inflation! Given the way things are, there’s just no need to translate Weimar into Japanese. Central banks don’t do money. They just don’t. They do reserves only. How many more times does this need to be proven?

|

. |

Tags: Bank of Japan,bank reserves,bond yields,Bonds,currencies,economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,interest rate fallacy,Interest rates,Japan,JGB,Markets,Milton Friedman,newsletter,QE,QQE