| Note: originally published Friday, Nov 1

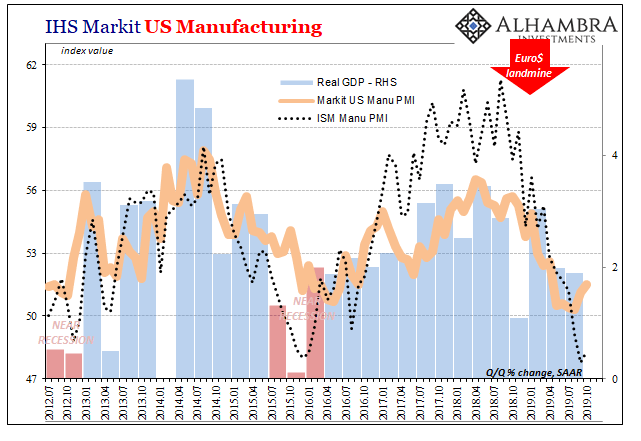

There wasn’t much by way of the ISM’s Manufacturing PMI to allay fears of recession. Much like the payroll numbers, an uncolored analysis of them, anyway, there was far more bad than good. For the month of October 2019, the index rose slightly from September’s decade low. At 48.3, it was up just half a point last month from the month prior. Most of that was related to a curious surge in New Export Orders. Having dropped to just 41.0 in September, this component rebounded more than nine points to 50.4 in October. It appears to be related to more one-off factors (either way) than any kind of surging macro contributions from a global economy emerging from its downturn. To begin with, overall New Orders (including exports) gained only 1.7 and remained firmly below 50 last month (49.1). At the same time, the level of current product fell to just 46.2 – the lowest in over ten years. |

IHS Markit U.S. Manufacturing, 2012-2019 |

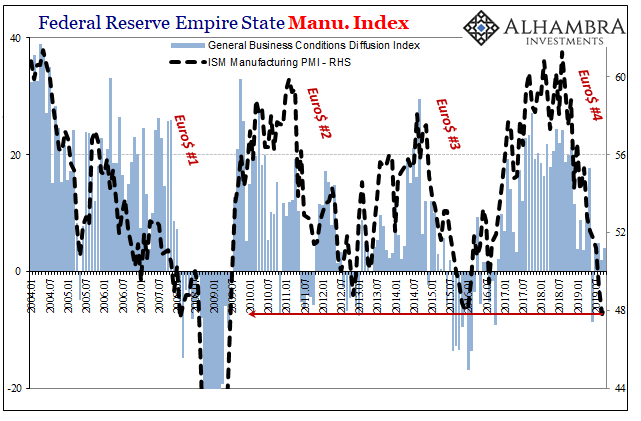

| The ISM spent a total of five months below 50 during the near recession of Euro$ #3. From October 2015 until February 2016, the “manufacturing recession” was captured by this sentiment survey but only getting as low as 48 (December 2015) before turning around and heading higher (above).

The current mainstream belief is that something similar will happen again (except the near recession part; we’re supposed to avoid even that this time around). The difference, many believe, will be the rate cuts. Recall that in December 2015 Janet Yellen’s Fed raised rates for the first time – if only that one time until the following December. Her FOMC had made the big mistake of dismissing “overseas turmoil” entirely while at the same time getting the related rising dollar all wrong. |

Federal Reserve Empire State Manu. Index, 2004-2019 |

There was no strong dollar; there can be no strong dollar. When it goes up, that’s not good for anyone.

Jay Powell’s Fed along with some help from international observers seems to have learned at least not to talk so much about the dollar other than to complain about its obvious correlation with global negatives.

But, if the rebound from rate cuts is true, then the bond market would have to be all wrong about the immediate future. It is forecasting several more of them (at least) over the next six months to a year. And the bond market has been way ahead of Jay Powell this whole time.

The current monetary policy position is, as stated this week, three’s enough. Really, I think they wanted to stop at two and reassess but weren’t given the chance due to the repo market overshadowing that second cut. That’s why there was the apparent rush, the need to have a clean, unspoiled event where Powell could get on TV and talk about his helping the economy without too many other uncomfortable (and still answered) questions.

However, that just demonstrates the problems with this latest Fed pause. “Something” tends to happen just when officials least expect. And they certainly never forecast these things in advance, which is why they keep following bonds with rate policy rather than how it is “supposed” to be the other way around.

In other words, the curves suggest that though much looks like it did last time around, Euro$ #4 to this point seems quite a lot like Euro$ #3 in the economy, the rate cuts this time don’t actually suggest a positive contribution. More like a negative confirmation. If the Fed feels it has to cut rates then perhaps it’s a little more serious in this go around.

It sure seems that way in overseas economies, particularly China. And one other thing we know, the global economy is synchronized. Up until now, the US economy’s slowdown is following along if a little further behind others already heading in the same wrong direction. If the rest of the world keeps grinding lower, then we have to ask what it could be that would suddenly decouple the US economy from them in a way it didn’t last year?

The only answers anyone appears willing to give are rate cuts and a strong domestic labor market. The latter is highly suspect in every possible sense, and there’s always less to rate cuts than what’s always just taken for granted (that, despite all recent history and experience, they are “stimulus”).

In terms of the labor market, it was inarguably better in 2018 (though arguably it still wasn’t good) and that didn’t lead to decoupling as had been projected, either. Why would a weaker labor market in 2019 be able to accomplish that feat?

For the specific US data today, the ISM and payrolls, what they continue to show is still a weakened trend in the US economy. Not recession, but certainly elevated recession risk. It can stay like this, as it has overseas, for some time more than it already has. There’s no time limit on it no matter how impatient everyone else can be.

The longer it goes, however, and the more the Fed feels rate cuts are necessary to try and push everything back in the right direction, the more elevated the risks. In that way, the ISM and the payroll numbers corroborate the curves. No recession today, but also no turnaround and therefore too much downside probability over the immediate time horizon.

The post Still Stuck In Between appeared first on Alhambra Investments.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: economy,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,industry,ism,ism manufacturing index,Janet Yellen,jay powell,manufacturing,newsletter,PMI,sentiment