There is quite an unusual price context for new week’s economic events, which include June US CPI, retail sales, and industrial production, along with China’s Q2 GDP, and the meetings for the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the Bank of Canada, and the Bank of Japan. In addition, the US Treasury will sell $120 bln in coupons while the US earned income tax credit and the child tax credit is rolled out.

The dollar surged even while interest rates fell. The US 10-year yield has risen in only four weeks since the end of Q1, and it has fallen in seven of the past nine weeks. It is off 111 bp since the start of the month. The 30-year bond yield fell to 1.85%, its lowest level since early February, before recovering ahead of the weekend.

It is not only at the long end that interest rates have adjusted. Consider that the December 2022 Eurodollar futures’ implied yield had risen to almost 56 bp before the recent employment report. This suggested the market was discounting a hike by the end of next year and around a 60% chance of a second hike. The implied yield fell to 43 bp, the lowest since mid-June, and settled at 46 bp last week. It is still pricing in a hike but appears to be pulling back from a second move. The implied yield and the Dollar Index have closely tracked each other, but the implied yield’s recent decline has not spurred dollar sales.

Moreover, it is not just that US rates have fallen in absolute terms, but so far here in July, the US 10-year yield has fallen by more than Germany and Japan. In fact, US long-term yields have fallen more than all the high-income countries, save Australia. The US two-year note yield is off about four basis points this month, which was a couple of basis points more than the decline in Germany and about five basis points more than the decline in Japan, which has declared another formal emergency for Tokyo that will persist through the Olympic Games.

Among the high-income countries, New Zealand’s two-year note stands out. It has risen by almost 30 bp since the end of July (to around 80 bp before consolidating), as the market moved to discount a hike later this year. The Reserve Bank of New Zealand meeting concludes early on July 14 in Wellington. It most likely will validate the market speculation, and a couple of days later, the CPI report will likely show a 0.7%-0.8% rise in Q2 to bring the four-quarter rate to around 2.7%-2.8%.

Growth is robust, and confidence is high. New Zealand has had better success than Australia in containing a new outbreak of the virus. The New Zealand dollar has not sustained a rally despite the shifting views on monetary policy may also encourage central bank officials to begin preparing the market for a hike, probably in Q4. The Kiwi recorded the year’s lows on June 18, slightly below $0.6925, which was only marginally below the March low and corresponds to the rally’s retracement objective since the end of last November 2. It retested the low before the weekend, and it held. A break could signal a move into the $0.6750-$0.6800 area.

The Bank of Canada meets later on July 14. The market is not looking for a signal about a rate hike as much as an indication that the broad economic assessment will allow it to proceed with tapering its bond purchases (now C$3 bln a week). The market seems closely divided about the timing of the next step. Still, given the recovery June employment report (230k jobs, a decline in the unemployment rate to 7.8% from 8.2%, and a sharp rise in the participation rate to 65.2% from 64.6%), and the recent comments from Governor Macklem and Deputy Governor Lane, we are inclined to look for another tapering move now.

The Canadian dollar has seen the gains scored in the wake of the April 21 hawkish surprise by the Bank of Canada unwind amidst the US dollar broad surge. Before the BoC announced it was tapering and foresaw closing its output gap in H2 22, the greenback traded slightly above CAD1.2650. Last week’s high was just shy of CAD1.26, its highest level since that April high. We also note that the exchange rate is more sensitive to risk appetites (using the S&P 500 as a proxy) than oil prices or the two-year interest rate differential. The greenback’s upside momentum stalled ahead of the weekend, with the help of the jobs data, and it on its session lows below CAD1.2450.

The Bank of Japan’s two-day meeting will conclude on July 16. Despite the ongoing economic weakness and deflationary forces, there is little more the Bank of Japan is willing to do. In fact, it continues to slowly and quietly reduce its bond purchases, but few call it tapering. The burden falls to fiscal policy, where there is increasing talk of another supplemental budget.

The BOJ is likely to do two things. First, it will tweak its economic forecasts. With a new formal state of emergency for Tokyo and foreign demand has not been sufficient to offset the compression of domestic demand, the growth profile may be adjusted lower. Previously, it estimated this fiscal year’s (through March 2022) at 4.0% and the next fiscal year at 2.4%. Since the last forecasts in April, the yen has depreciated by about 1% against the US dollar and about 0.8% against the Chinese yuan, which is probably too small to impact inflation expectations. Crude oil prices are up around 11%. The BOJ estimated that CPI would rise by 0.1% this year and 0.8% next year. A small upward adjustment to this year’s forecast would not be earth-shattering and would still be quite low by any metric.

Second, the Bank of Japan is at the forefront of central banks for whom climate change will clearly impact policy. The Federal Reserve is on the opposite side of the spectrum as Chair Powell has played it down as a consideration. At the June BOJ meeting, Governor Kuroda indicated that details of a climate change measure would be provided at the July meeting. Most are imagining a lending facility that banks could draw on at favorable terms for loans to businesses reducing greenhouse emissions, such as carbon, or boosting R&D expenditures for climate change. Other lending schemes are 10-20 bp discounts. To boost the incentive, longer maturities for the loans may be offered.

Japanese officials may be as surprised as anyone by the recent pop in the yen. Recall that on July 2, shortly before the US employment data, the dollar set a new 15-month high against the yen near JPY111.65. The dollar fell to almost JPY109.50 last week as US bond yields fell and risk came off more broadly. Safe-haven nomenclature does not do justice to what is likely happening. The yen (or Swiss franc) are not bought because these countries are safe havens in any meaningful sense. Nor are they being bought because of their net international investment surplus positions. Rather, the yen (and Swiss franc) are bought to reduce the short exposure taken on to fund the purchases of other assets, like stocks and/or emerging markets. When the asset is sold, the funding currency is bought back.

China is the first large country to report Q2 GDP figures. They are due early July 15 in Beijing. June trade figures are due out before it, and the trade surplus appears to have widened in Q2 over Q1. The State Council suggested a pivot was taking place toward support from restraint, and ahead of the weekend, the PBOC surprised many by cutting the required reserve ratio by 50 bp across the board. In fact, some saw the move as a possible hint that the GDP figures may disappoint. The median forecast in Bloomberg’s survey is for a 1.0% quarter-over-quarter expansion. However, new forecasts have seen the median edge lower over the past week. While this is faster than the Q1 pace (0.6%), if the Chinese economy is near the peak of the growth cycle, it is rather disappointing. The four-quarter average was about 1.4% in 2019 and 1.6%-1.7% in 2016 through 2018.

By the wit of Chinese officials or as a reflection of the vagaries of the market, the net result has been a steady yuan. It has risen by about 0.75% against the dollar so far this year. After the yuan rose in seven of eight weeks in April and May, Chinese officials raise reserve requirements on foreign currency deposits and signaled through its dollar fixings that they were displeased. With last week’s losses, the yuan has now fallen for six consecutive weeks. The dollar has approached the CNY6.4950 area, which has capped it since late April. Even after the PBOC unexpectedly announced a 50 bp cut in the required reserve ratio ahead of the weekend, the yuan edged to new highs for the day. China is expected to soon launch a southbound link that allows Chinese investors to more easily purchase foreign bonds. Like boosting the Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor (QDII) quota, Chinese officials can deploy it to help offset the upward pressure on the yuan from incoming portfolio flows.

The US economic calendar is jammed next week with inflation (CPI and PPI), real sector (retail sales and industrial production), and survey (Beige Book, Empire State, and Philadelphia surveys, and University of Michigan consumer confidence, and inflation expectations). Some disappointing data has seen some cautiousness creep into Q2 GDP (due July 29) estimates. The New York Fed’s GDP now puts it at 3.2%, while the Atlanta and St. Louis Fed models stand at a more impressive 8.48% and 7.9%, respectively. The real sector data will allow economists the opportunity to fine-tune their projections.

Still, policymakers seem more concerned about price pressures than they are that growth will slow sharply in the coming quarters. By one count, the FOMC minutes for the June meeting cited “inflation” 83 times compared with 55 times in the April minutes. US headline CPI year-over-year rate has accelerated every month from February (1.7%) through May (5.0%). Prices may have stabilized last month as the 0.5% month-over-month increase offsets an increase of the same magnitude last year, after three months of falling consumer prices.

The ECB has redefined its inflation target from the tortured “close to but below 2%” to a “symmetrical 2%”. It seems vaguely similar to the Fed’s average inflation target, especially without the “average period” purposely not being specified. Previously, the Fed and the ECB had a “bygone” approach. There was an appreciation for variable lag times, and the target was generally understood as a medium-term goal. What happened previously does did not impact the pursuit of this year’s target. That is no longer true.

It is a type of forward guidance to signal that an overshoot of the formal target will be tolerated to “compensate” the past undershoot (Fed) or as a result of the efforts to avoid deflation or disinflation (ECB). Although some observers put more emphasis on it and see it changing the DNA of the ECB, we note that on the day it was announced, the euro snapped a three-day fall to rise by slightly more than 0.40%, its best showing in nearly three weeks. Moreover, Eurozone bond yields fell 4-8 bp last week, and the German premium widened. Moreover, despite claims of breaking from the Bundesbank, the fact of the matter is Bundesbank President Wiedmann explicitly backed the new symmetrical understanding of the medium-term objective.

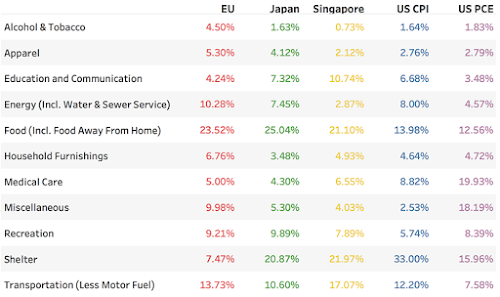

| What is often lost is that although central banks from high-income countries target 2% inflation in some fashion, what is being measured is not the same thing. I had the privilege of working with four global finance graduate students at Fordham University Gabelli School of Business (Hans Zdolsek, Christopher Consolo, Hangwei Zhang, and Edvinas Rupkus) who looked closer at the different baskets and weightings for a few selected consumer price measures and devised a harmonious classification.

Significant differences in weightings point to the risk of asymmetrical shocks. The EU gives energy the most weight. Food, including away from home, has nearly twice the weight in the EU and Japan as it down in the US. Medical care in the US has a greater share of the US consumer inflation basket than the EU and Japan. Shelter costs in the EU are significantly less than in the other baskets. Many observers emphasized that the new guidance by the ECB will allow for inflation to overshoot the 2% target. In a lesser appreciated signal, the ECB said it intends to incorporate owner-occupied housing costs into its harmonized measure. This will likely boost measured inflation by a few tenths of a percentage point. |

Consumer Price Measures and Harmonious Classification |

| The students took the different weightings and looked at how the different measures would vary if a different weighting scheme was used. For example, how much is Japan’s deflation a measuring issue? The weightings used by the US CPI and PCE deflator are different. Is it material? Using data from this past April, a matrix was created.

It shows that if US CPI (4.42%) used Japan’s CPI basket weightings, it would have been fractionally lower (4.24%). On the other hand, even if Japan used the US CPI weightings or the EU’s HICP measure, or Singapore’s, it would still have experienced deflation. The EU’s HICP measure gives slightly higher inflation than the other configurations would. Thus, the HICP weighting would have given the US somewhat greater price pressures than its own measures. |

Inflation Matrix |

No matter how it is measured, the US inflation is running ahead of the EU, Japan, and Singapore. While several central banks, including the Federal Reserve, have insisted on putting more weight on actual performance rather than forecasts, expectations still matter. It is difficult to use some market-based measures of inflation expectations when the Federal Reserve insists on purchasing inflation-protected securities. That said, the 10-year break-even has fallen by nearly 20 bp since May 17 (to ~2.23% before recovering to almost 2.30% before the weekend), while the nominal yield has fallen from almost 1.70% to l.25%. It also bounced ahead of the weekend. The five-year-five-year forward inflation swap has also fallen from around 2.60% in mid-May to below 2.20% before ticking up before the weekend.

Tags: Bank of Canada,Bank of Japan,China,ECB,Featured,federal-reserve,GDP,inflation,Interest rates,newsletter,RBNZ