Governments are taking a page out of the play book that monetary policy began a decade ago – which will lead to even higher debt levels.

During the throes of the financial crisis almost a decade ago Mario Draghi, then President of the European Central Bank (ECB) pushed the ECB’s mandate to the limits with his speech in July 2012:

“within our mandate, the ECB is ready to do whatever it takes to preserve the euro. And believe me, it will be enough”

This was during a time when Greece, Portugal and Ireland had already received financial stabilization support from the European Union, IMF and ECB. Concern that rapidly rising government bond yields in southern Eurozone countries would create a domino effect of financial crises requiring financial stabilization packages across the region. Speculation was escalating that countries could start departing the Eurozone. Draghi then backed up his vows by purchasing government bonds to stabilize yields.

That Was Then, This is Now…

Fast forward to the current pandemic-induced crisis…

The IMF estimates that governments have already provided more than $14 trillion in support through increased spending and tax cuts. And just this week Rishi Sunak, UK finance minister, is promising.

“We’re using the full measure of our fiscal firepower to protect the jobs and livelihoods of the British people, … First, we will continue doing whatever it takes to support the British people and businesses through this moment of crisis … Second, once we are on the way to recovery, we will need to begin fixing the public finances – and I want to be honest today about our plans to do that. And third, in today’s budget we begin the work of building our future economy”

Reuters; 03/02

This is in addition to the almost $300 billion pounds the UK has already spent on emergency programs and tax cuts since March 2020.

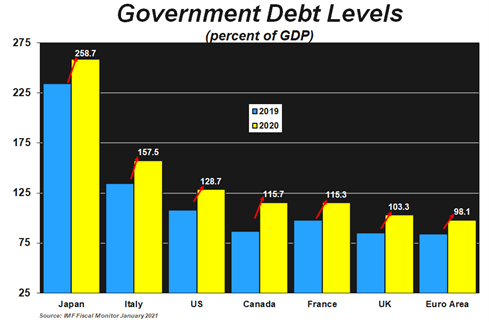

And the UK isn’t the only government with this mindset. Draghi himself, now Prime Minister of Italy, has the daunting challenge of restoring growth to a country that had stagnated even before the pandemic. Even with Italy already saddled with debt approaching 160% of GDP, Draghi is likely to increase spending programs and reduce taxes to spur economic growth.

Watch Jim Rogers on the Latest Episode of GoldCore TVThe US government is no exception, with Janet Yellen taking the helm of the US Treasury pushing for up to $1.9 trillion in additional stimulus spending, along with another chunk of additional spending on infrastructure and renewable energy initiatives. At the same time monetary policymakers are committing to keeping rates low for the foreseeable future to support their respective economies. |

|

The Options Are LimitedIf we fast forward further to the days after Covid-19. The high and continually rising debt levels limit monetary policy options; monetary policy tightening becomes extremely risky in an environment of high debt as it risks quickly tipping an economy back into recession. High debt levels also dampen economic growth, which encourages more expansionary fiscal policies, which then further adds to debt levels, which then dampens growth yet further, which then encourages yet more fiscal policy expansion,…, and so on. Governments can reduce debt in two ways, either inflation/financial repression or shift to policy austerity. This means higher taxes and cuts to government services. Let’s first us look at what is needed to reduce a government’s debt to GDP ratio. The basic principle is that the growth of nominal GDP (which is actual GDP growth + inflation) plus the primary balance (the government’s deficit/surplus as a percent of GDP not including the payment on its debt) must exceed the total interest paid on its debt. |

For example, if a country’s nominal GDP growth is 4%, and the primary balance is -3.5% of GDP (meaning that the country spends more than its revenues), and the interest the government pays is 2%, then the debt to GDP ratio will rise, because 4% + (-3.5%) is less than 2%. However, in the example above if the country’s expenditures are equal to its revenues (a balanced budget) then the debt to GDP ratio will decline, because 4% + (0%) is greater than 2%.

“Whatever it Takes” Has Only Two Choices

As for the choices on how to reduce debt to GDP ratios, the lesson is that inflation helps reduce a government debt to GDP. This statement presumes that government deficits are brought under control. It also assumes that interest rates are lower than the inflation rate through interest rate caps.

The other option is political austerity. And if history is any indicator governments that implement harsh fiscal austerity measures, get quickly voted out of office.

Japan has the highest government debt level in the world. The majority of the debt held by the Bank of Japan. Given the absence of a debt crisis in Japan, adherents to Modern Monetary Theory have been encouraged to argue that European and North America countries should follow Japan’s example. This means the central banks should buy more government debt as the governments embarks upon capital (and social) infrastructure expenditures. In this case, government debt levels will rise significantly higher in the coming years. And this could end – with an inflationary surge and suppressed interest rates.

So “whatever it takes” becomes; “whatever we can given our very limited financial, monetary and political options!“

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Daily Market Update,Featured,GDP,government debt,inflation,money printing,newsletter