What happens when we are stunned and dazed? We filter out the noise to focus on the bare basics by getting back to our instincts, acting reflexively based upon our deeply held beliefs and especially training. When faced with a crisis and there’s no time to really think, shorthand will have to suffice.

That’s what was so odd about 1930, as I wrote about last week. The stock market crash had happened during the prior October, but while that had meant panic on Wall Street generally speaking there wasn’t too much of it outside lower Manhattan.

To begin with, these kinds of things happened before.

When the economy began to follow share prices into the toilet, there was no sense of massive urgency. Everyone knew that the prospects were grim, nothing good was going to come of the thing. For the most part, however, during 1930 there wasn’t a sense it would be anything different than those depressions of the past.

Even the worst ones were awful but temporary. In fact, New York’s Governor Franklin Roosevelt wrote to a constituent during that year telling the man to just hang in there, urging this local voter to “not to yield to the counsels of despair because depressions always come to an end and business also eventually adjusts.” Time was on everyone’s side.

As was the government. Contrary to modern biased views, Hoover’s administration was far from the do-nothing laziness FDR would describe in his political campaign of 1932 (which was then transcribed by the newspapers as fact). The Federal Reserve wasn’t idle, either, merely, like Hoover, grossly ineffective. No one knew that at the time, though.

|

One New York Times article written in March 1930 sounds way too familiar:

The difference, as Milton Friedman and Anna Scwartz would show decades later, was (and is) that monetary policy might have been uniformly called “easy-money” throughout the press but in actual practice it had been entirely opposite. |

|

| As the year rolled on, though, there continued the steady stream of loud, authoritative voices to sound out this cautious optimism. The message of “just hang in there” was one which reverberated throughout. And it wasn’t like it was out of line or out of order. As Alfred Sloan, President of General Motors, said in September 1930, “Business has turned a corner and is now on a slow but sure return to normal conditions.”

The President of GM (and the mountain of others like him) would surely know what he was talking about. Most people were and still are willing to give “easy-money” policy as well as the typical array of government rescues the benefit of the doubt – at first. Just going back to the last time we did this, in 2008, for quite some time there was the combination of Bear Stearns and the Bush “helicopter” which provided official support behind the rebirth of this same idea. Be patient! Those even managed to turn GDP positive for Q2 2008, making it seem like the government rescues really were working. It wasn’t until later when it became clear, first in dollars and then everywhere else, that they really weren’t working, leaving even the best companies to ditch the just-hang-in-there mantra for the every-man-for-himself second phase of GFC1. For the record, I’m not saying this is 1930 only that there is a lot we can learn about similar sets of circumstances. We’ve seen these things before (as is our annual August 9 reminder). |

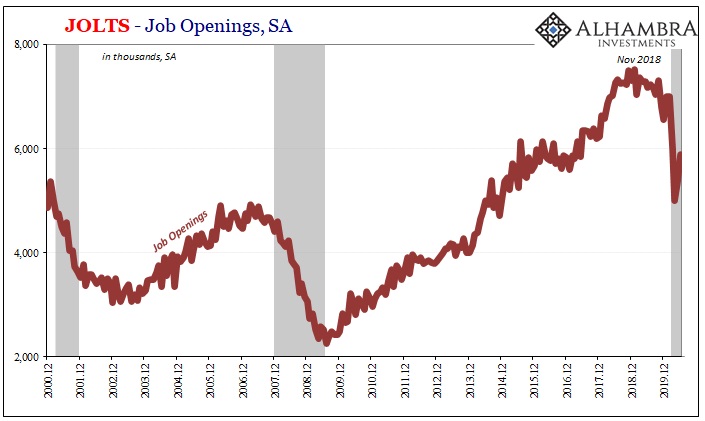

Jolts - Job Openings, SA 2000-2019 |

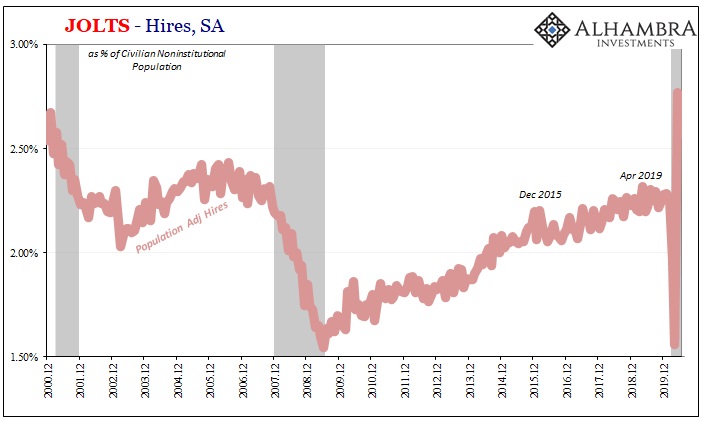

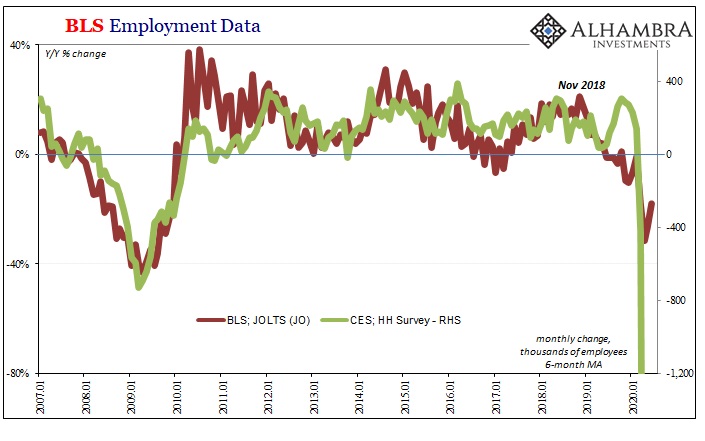

| I think what’s most interesting about the JOLTS estimates which were released today is how they weren’t worse back in April and May at the bottom. The level of job openings (JO), in particular (Hires just all over the place, as you’d expect given the wild swings in the labor market from shutdown to reopening), while down by a whole lot have quite clearly disconnected from more fundamental employment indications. |

JOLTS - Hires, SA 2000-2019 |

| Like the rest of the BLS data in the CES, or payroll reports, broadly speaking, JO already starts out less than impressive as a “V.” The level has rebounded from the bottom set in back in April, rising 18% over the two months which have followed (the latest figures are for June 2020, one month further behind the CES).

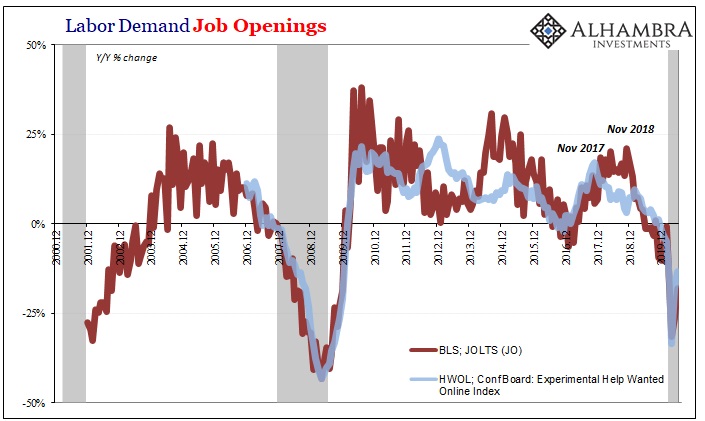

It’s yet another opportunity for huge positives to be misleading. And while that’s still 16% lower than it was in February, and down 18% year-over-year, those comparisons while troubling aren’t really what I’m talking about. In fact, according to the BLS version of labor demand as well as the Conference Board’s HWOL series, what we just went through wasn’t even as bad as the Great “Recession” so far as general, baseline labor demand might have been concerned. |

Labor Demand Job Openings, 2000-2019 |

| You can see what I mean instead when you begin to compare job openings (either series) to the rest of the employment data. Versus hours worked, for example, there now seems to be an especially large discrepancy: |

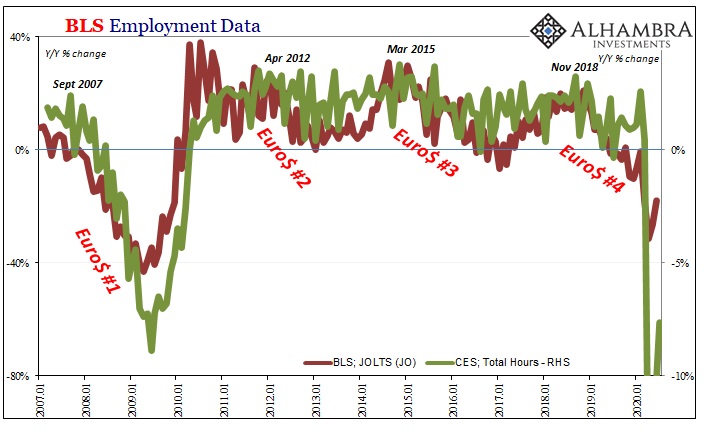

BLS Employment Data, 2007-2020 |

| What it suggests is that employers cut way back on employees because the amount of work they had for their staffs simply collapsed; nothing surprising in the least. However, the difference in job openings indicates that advertising for positions wasn’t scaled back by anywhere close to the same crash level, likely because a large proportion of employers have been thinking this is all just a temporary disruption.

For a huge number, they didn’t just cancel online job postings thinking why not leave the ad up because even if they hadn’t intended to fill the position during May, June, or July (or August and September) they fully expect that once the full “V” takes shape everything will be right back to normal. Obviously, a great many businesses did take down their job postings, but since it wasn’t commensurate with the same during the Great “Recession” or near the depths of the employment drop a few months ago it would seem reasonable that the number of firms clinging to just-hang-in-there is substantial. The discrepancy is even larger when you compare JO to either the HH Survey or the Establishment Survey, each likewise pointing to a discrepancy of optimism this time around. |

BLS Employment Data, 2007-2020 |

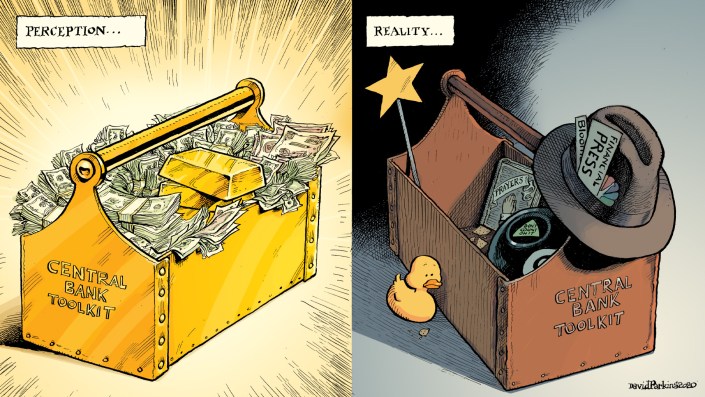

| Quite a lot of people believe today that the Fed flooded the world with dollars and liquidity. Most if not all of the same people think that the federal government has been “stimulating” in a way that would make FDR blush. More, perhaps many more, believe some of those things while also thinking that what happened to the economy was strictly a non-economic affair.

Business leaders (especially those in Germany) have generally been very upbeat. Altogether, like flipping a switch they turned the economy off and the thinking goes it will be relatively easy to turn it back on again; Jay Powell and the Trump administration each playing their powerful roles. Not everyone believes this, obviously, but across the economy (and stock market) this is a widely held position. While you can’t reasonable call it unbridled optimism, what happens if or when the cautious optimism suggested by JO compared to underlying employment figures gets trampled on by a distinct not V-like trendline? As I wrote last Friday with the release of July’s CES, the June JOLTS comparisons seem to set everything up for a second wave. Economy, not COVID. |

Employment Rates, 1995-2021 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: currencies,economy,establishment survey,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,federal-reserve,hours worked,household survey,job openings,jolts,Labor Market,Markets,Monetary Policy,newsletter,stimulus,total hours worked,unemployment rate