According to the latest figures, Japan has tallied 56,074 total coronavirus cases since the outbreak began, leading to the death of an estimated 1,103 Japanese citizens. Out of a total population north of 125 million, it’s hugely incongruous. For now, however, it does present an obvious reason why the government there didn’t go to such deliberate lockdown extremes as so many other places around the world.

As we’re now halfway through August, I stand by my original statement and the sentiment behind it; which was that in a couple years we’ll be far more focused on the economic fallout while wondering what the hell everyone was thinking to have provoked it.

I wrote late in February as GFC2 was coming into full view:

I claim no expertise in diseases or virology, so make of it what you will. There is no doubt this is a serious condition, and not for just China, but I also think that it’s being overhyped – though it is hard to know one way or the other.

|

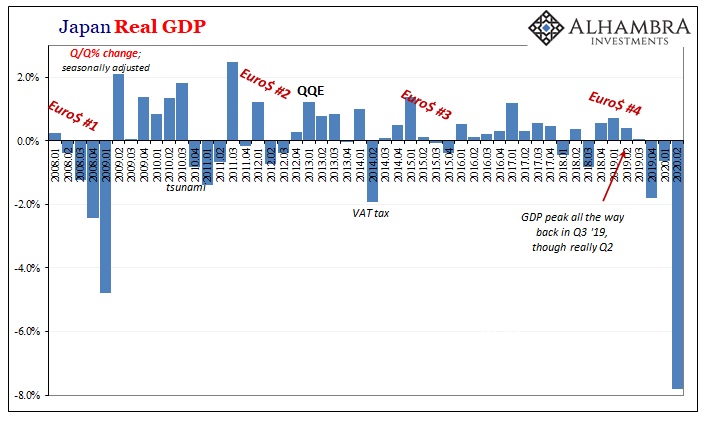

The statistical models were way, way out of line, and whenever they come to the forefront as the only “data” it’s usually your first clue (few of them are worth paying any attention to, in almost every discipline outside of quantum physics). The actual data, on the other hand, continues to indicate that the economic costs are piling up far and away much higher. Japan is an interesting case where that might be concerned. The scariest hype, after all, was rendered as “Science” due to the Diamond Princess sitting in emergency dock right within the harbor of its largest city. The Japanese were screwed, many said. Yes, just not directly as a consequence of the pandemic. Instead, the rather predictable, I think, result of overreaction to it. Though Japan escaped the higher levels of virus numbers, its economic numbers look all-too-familiar. |

Japan Real GDP, 2008-2020 |

| And it’s also an interesting case for the other set of failed models, those employed by central bankers and Economists the government had been seeking out for advice on how to play things. Updated GDP estimates show that before it’s worst quarter in its modern estimates (Q2, reported today) the Japanese economy had been in trouble for a long time – going all the way back to the end of 2017 (just like everyone else in the global economy). |

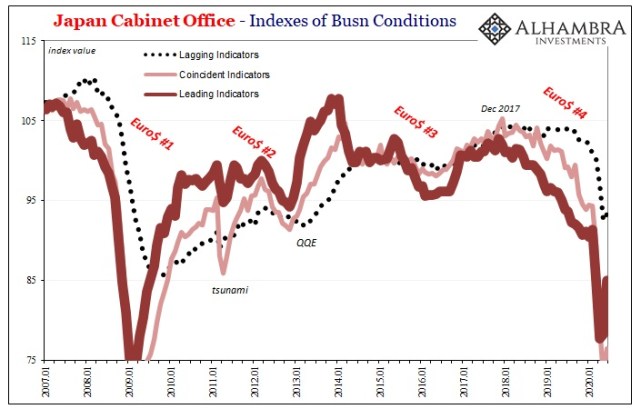

Japan Economy, 2016-2020 |

| Long before COVID, the government had come to believe, because BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda had told Prime Minister Abe, that the economy had shaken off 2018’s “unexpected” setbacks and by the middle of 2019 monetary officials were sure that everything was right back on track; so much so, that they recommended pushing ahead with the long-delayed VAT tax hike scheduled for the start of October 2019.

And they went ahead with it in the process making a mistake, another big one. |

Japan Cabinet Office, 2007-2020 |

| The GDP figures reveal that the Japanese economy hadn’t actually shaken off 2018 at all, instead, as usual, right when central bankers said it was going to accelerate the system went in the totally opposite direction; though the GDP level was ever so slightly higher in Q3 2019, it was practically unchanged meaning that the prior economic peak was all the way back in Q2 when the tax decision was being made.

Sputtering for three-quarters of a year and then the COVID confidence. But that’s all in the past, and there’s absolutely nothing the Japanese can do about it now. What we everyone around the world wants to know, starting in global bellwether Japan, is how well anyone might be doing getting themselves out of this debacle. The output data isn’t quite advanced far enough yet, so instead we’ll have to rely initially on “soft” data like sentiment. Leading indicators, and whatnot. |

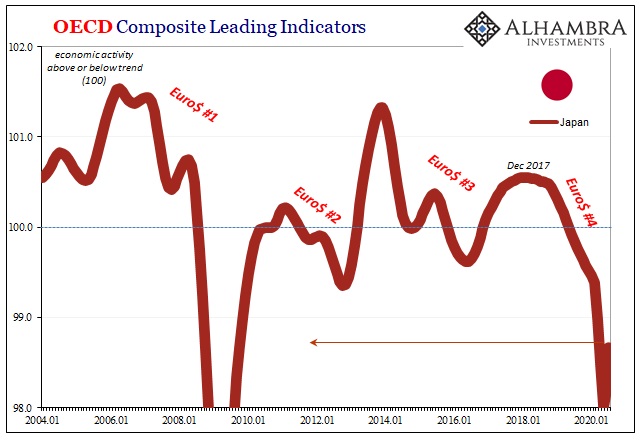

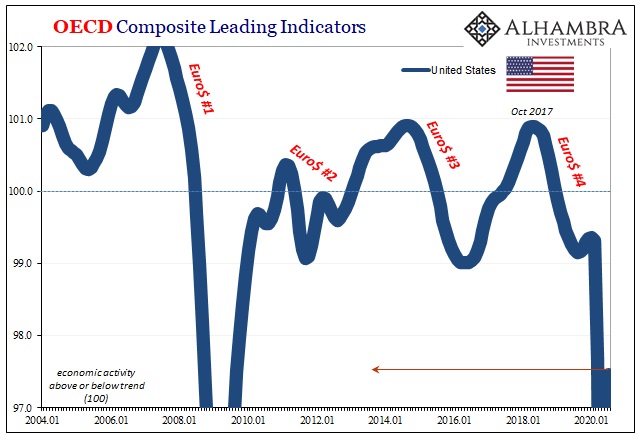

OECD Composite Leading Indicators, 2004-2020 |

| Like we see in so many other places around the world, yes, it’s a rebound as things are being reopened but that’s not at all the same thing as recovery. On the contrary, where sentiment is highly biased to the upside the latest readings for the various data sets are alarmingly slow at coming back up.

All of them (Germany’s ZEW, of course, the wild exception) instead indicate that whichever economy, including Japan’s, is still getting worse if at a slower rate. The Cabinet Office estimates, for example, in June 2020 remained equivalent to the first half of 2009. |

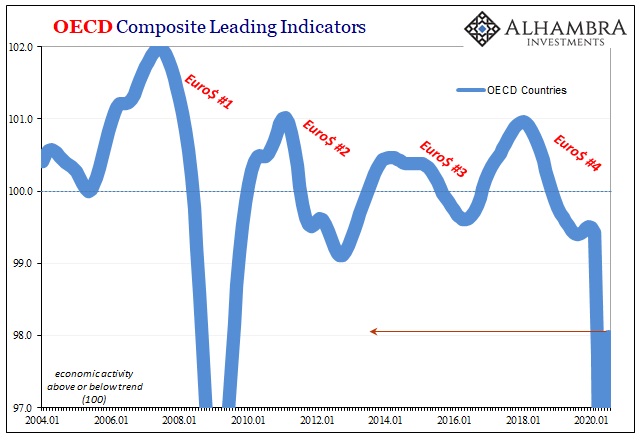

OECD Composite Leading Indicators, 2004-2020 |

| It seems most people have it in their minds more right now is more like the second half of 2014.

The OECD’s leading indicator is bit more on the upswing in being similar to the second half of 2009, but it’s latest estimate is for the month of July. That far along into the reopening rebound isn’t consistent with a modest “V” let alone the recovery trajectory many people are being led to believe is being engineered by all the same people who fed you their models in the first place. |

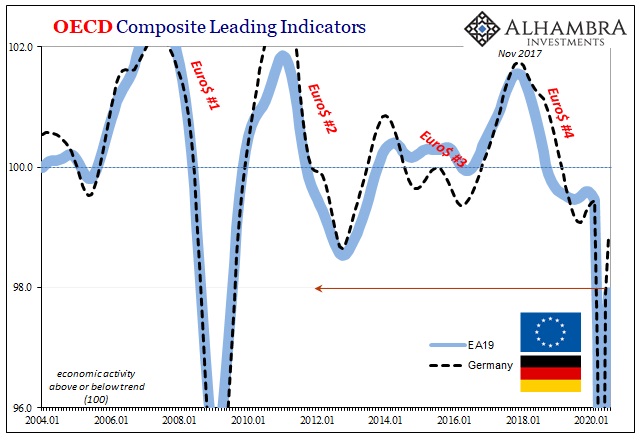

OECD Composite Leading Indicators, 2004-2020 |

| So far as the OECD’s estimates show, Japan is among the best cases of leading indicators but not materially different from the others. Most of the rest, including the one for the United States, are rather disconcerting. Again, these are all for July.

Not only do they remain extremely low, as purported forward-looking measures they’re telling us what to expect for months further down the road from July. Worst still, the rate of improvement in all these countries from June to July dropped by a significant margin. |

OECD Composite Leading Indicators, 2004-2020 |

| To sum it up: the global economy for the rest of the summer into autumn was anticipated to be getting worse at a much slower rate in June but then it was thought it will get worse at only a slightly slower rate in July. At best, that pushes the beginning possibility of recovery further toward the end of the year, raising the risks everything bad in between (including disappointing all those hanging on for the “V” that’s being talked about but nowhere to be found).

More likely, it raises the probabilities that “recovery” will, like all of them after the GFC1, end up every bit deserving of the quotation marks which will continuously surround it. “L.” |

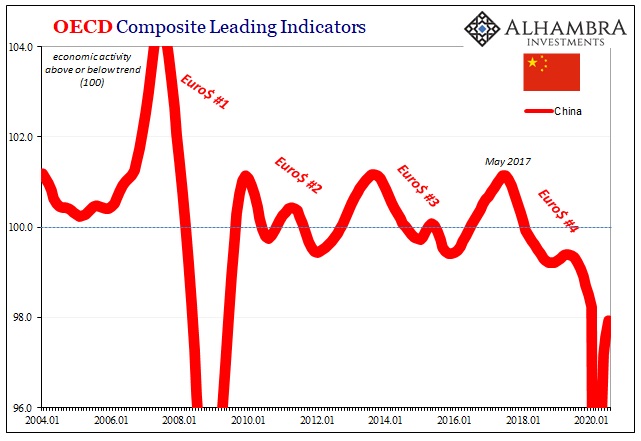

OECD Composite Leading Indicators, 2004-2020 |

The leading indicators like the rest of the hard data we do have, these are not outliers, either. From China retail sales to US industry to even German services (no matter how happy dreams of stimulus make service providers like manufacturers there), the world isn’t coming back very quickly at all. Being a bit off the bottom just is not the same thing.

After the biggest drop on record in many places, that’s an enormous red flag. As is the fact we’ve seen this sort of asymmetry before, and all the same models which had promised how such a thing was impossible.

If it does keep up like this, will anyone even remember COVID?

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: China,COVID,currencies,economy,Europe,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Germany,Japan,Markets,newsletter,OECD,real GDP,recession,recovery