|

It used to be that at each quarter’s end the repo rate would rise often quite far. You may recall the end of 2018, following a wave of global liquidations and curve collapsing when the GC rate (UST) skyrocketed to 5.149%, nearly 300 bps above the RRP “floor.” Chalked up to nothing more than 2a7 or “too many” Treasuries, it was to be ignored as the Fed at that point was still forecasting inflation and rate hikes. Total financial resilience otherwise. Yesterday was, of course, another quarter-end. Rather than surge, however, DTCC reported that the GC repo rate (UST) was practically zero. Zilch. According to their calculations, the weighted average interest rate for all of the repo transactions which took place within its purview on the final day of Q1 2020, a tumultuous three-month period if ever there was one, the GC number wasn’t even a full basis point. Just two, count ‘em, two pips (or 0.002%, if you prefer). Hurray for Jay Powell! That’s what people are being told, especially by the so-called experts. Seriously, there are congratulations flying around from the people we are led to believe know what they are talking about (except when it comes to the tiny matter of “too many” Treasuries, but we’ll get to that in a minute). As I’ve been attempting to do this week, we all need to clarify our terms. The details matter, but we’ve got to be on the same page regarding the big stuff first and foremost. I asked yesterday, what is the Fed? The answer isn’t “central bank.” |

UST Yields & Money Alternates, 2007-2009 |

| What I mean is paramount, now more than ever; the Fed is nothing more than a domestic bank authority. Therefore, its assigned job (much of it self-assigned) is to safeguard the US banking system. A noble project, to be sure, but is that the same thing as what we all are thinking about when we expect what central bankers have been calling financial “resiliency?”

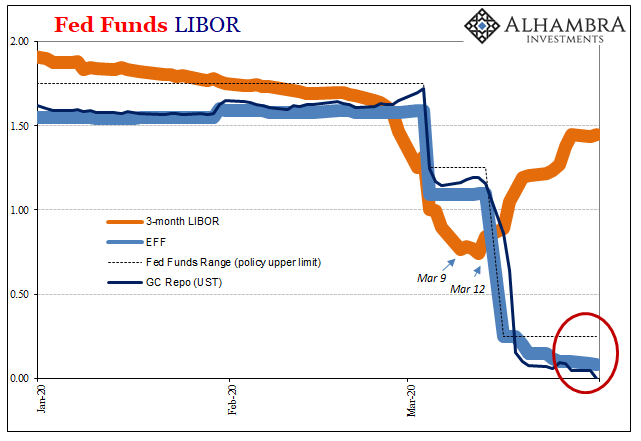

Put another way, we are left to presume that if the Fed does its actual job as domestic bank authority then there’s nothing left to worry about. Absent any other shocks, such as a coronavirus pandemic, Jay Powell’s got it all covered. To put it as simply as I can: so long as there isn’t another Lehman Brothers, then we’re supposed to believe the banking system must be doing fine we assume because the Federal Reserve is doing its job. Preventing bank failures, then, would seem to be the single most important outcome. If there isn’t a banking crisis, then we’re all good otherwise? No. It’s a grave misconception and one which monetary authorities had made a dozen years ago. And I’ll show you exactly how, and therefore just what I mean. I’ve used this chart (above) before when making my point about the low repo rate. It may seem counterintuitive, but during the worst parts of GFC1 the repo rate as well as EFF (effective federal funds) and yields on T-bills all plummeted. That’s not how we’re led to believe a monetary crisis happens. I’ve modified the chart by making one addition to it: 3-month LIBOR. The track of this offshore eurodollar money rate conforms much better to our mainstream crisis imaginations. What’s important is in the middle between Bear and Lehman. |

Fed Funds LIBOR, 2020 |

| While bill spreads and GC repo rates kind of went back to normal, LIBOR never did. Furthermore, during those middle months of 2008 (what I’ve called the midpoint period) Fed officials like Ben Bernanke, Janet Yellen, and the perpetually puzzled and in-over-his-head Bill Dudley all convinced themselves they had done it; they had solved the crisis.

Why did they begin thinking this way? Ironically, Bear Stearns. Officials looked at GFC1 up to the middle of 2008 from the perspective of a banking crisis. By successfully shepherding and aiding Bear’s orderly demise into the willing (they said) arms of JP Morgan, the FOMC took everything as a sign of success in its primary quest to aid the banking system – which, as the domestic bank authority, the Fed was very pleased to do. But was GFC1 a banking crisis, or a dollar crisis? You might not think this distinction matters; in fact, we’ve all been taught from the beginning how it doesn’t. The very history of GFC1 as well as any minimal investment of time and honest analysis comes up with the contrary answer. Every single time. By focusing its efforts on aiding banks and preserving the domestic banking system, the Fed paid little effort and attention to the wider global (euro)dollar system. As a consequence, what started out as a dollar crisis became a banking crisis – two of them, actually. The first one smoldered underneath, no matter what the Fed did, until it consumed Bear Stearns. The second one erupted in the summer of 2008 eventually devouring the GSE’s, Lehman, AIG, etc. In other words, by viewing everything through the lens of the banking system the monetary authority never actually fixed the real monetary problem (global dollars, or eurodollars). As denoted by that persistent LIBOR spread throughout the middle of 2008. The banking system itself was telling the Fed that for all the focus on domestic banks it wasn’t producing the desired effect in eurodollars. Ben Bernanke had it upside down. The dollar crisis came first and because it had been left to fester that is what eventually sparked both banking crises. And it’s because our monetary authority is no monetary authority at all – it is, again, purely a bank authority and acts in accordance with that viewpoint and ideology. Therefore, it proceeds from a false assumption; namely, that if we don’t have another Lehman then the financial system must be A-OK! Thus, the economy well-guarded and on solid ground. This is, in large part, what led so many “experts” to the conclusion that there had been “too many” Treasuries since 2017. The lack of a banking problem was considered the full scope of evidence and therefore conclusive about an inflationary acceleration with the economy freed from any further drag; no consideration was given for a still-ongoing dollar system problem even though it was all right there in the curves the whole time! That was the dichotomy: from the perspective of just the banking system, great job Fed! From the far-flung corners of the eurodollar system, you’re fooling yourselves guys. The truth is, we can still experience a dollar crisis without it producing a banking crisis. For one, the former precedes the latter. Whether or not a dollar crisis becomes a banking crisis comes down to the manner in which the dollar crisis impacts the entire financial and economic system. Yes, the shadow shadow run scenario. As I’ve written consistently, I don’t expect a banking crisis this time around because the banking system learned about the drawbacks of central banks (CBINO?) who have no real ability to handle (or recognize and appreciate) a dollar crisis. They didn’t need Basel 3 to tell them to be better prepared for a repeat. In fact, the banking system actually fixed itself starting right during GFC1 by increasingly opting out of the dollar system! Thus, while the banks aren’t going to go down one by one like last time, that doesn’t mean everything will be hunky dory; quite the contrary. The “strengthened” banking system creates an every-man-for-himself situation where those strong banks end up as islands in a liquidity desert; they’ve got what they need – but no one else does. Corporate bond markets and even entire national systems; the shadow shadow run of eighty Argentinas. Which brings us to LIBOR today. |

Eurodollar Futures, 2020-2021 |

| While the fed funds rate continues to drop and GC repo right down to zero already, the key 3-month LIBOR tenor once more perpetuates that same queasy positive spread just like it did in the middle of 2008. Sure, Jay, and all those other experts, go ahead and squawk about how resilient the banking system is meanwhile that same banking system continues to sound the alarm about the dollar system (collateral being a big part of this).

Dammit people, it’s a f-ing road map!!! We see this not just in what’s taking place now, but more importantly in what scenarios are being priced out in futures markets for the immediate future. |

Eurodollar Futures Curve, 2020-2024 |

Look at what has happened to the eurodollar futures curve: the front end has blown out, meaning sold off, while the intermediate term contracts are bid heavily. The eurodollar futures curve flattens out in the all-important 2021-22 range while the 2020’s continue to match LIBOR.

What the market is saying is incredibly simple: there’s a dollar problem out there in the world and it isn’t going away anytime soon. It doesn’t matter whether another Lehman happens or not, the negative consequences of this continuing dollar shortage, despite dollar swaps, QE’s, and now FIMA, are more and more assured (that’s the buying in the ‘21s and ‘22s)

In short, while the coronavirus dislocation might be temporary GFC2 won’t be; the dollar rather than banking crisis which has precipitated this second one will almost certainly produce long-lasting systemic damage. The global economic recovery unnecessarily harmed by the lack of attention to money.

It’s not just eurodollar futures, either. For the sake of brevity and space I’ve omitted the rest of the bond market and other curves which are a practical carbon copy.

All of it because our monetary authority is actually a bank authority (and a domestic one) which focuses on banks rather than money but whose entire goal has been to make it seem their domestic bank authority encompasses all the roles of a monetary authority (so long as you never, ever ask any questions). It may not sound like much of a difference, or maybe it sounds confusing, both of which aid in this terrible predicament.

Lehman Brothers like Bear Stearns was a casualty and symptom of the overriding dollar shortage, not the whole thing of GFC1.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bear Stearns,Bonds,collateral,currencies,economy,EFF,eurodollar futures,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,gc repo rate,GFC1,GFC2,jay powell,Lehman Brothers,Libor,Markets,newsletter,repo,T-Bills