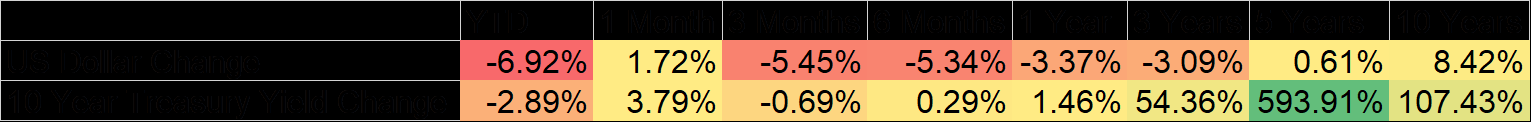

| Today Credit Suisse released its latest annual global wealth report, which traditionally lays out what has become the single biggest reason for the recent “anti-establishment” revulsion: an unprecedented concentration of wealth among a handful of people, as shown in Swiss bank’s infamous global wealth pyramid, an arrangement which as observed by the “shocking” political backlash of the past year, suggests that the lower ‘levels’ of the pyramid are increasingly unhappy about.

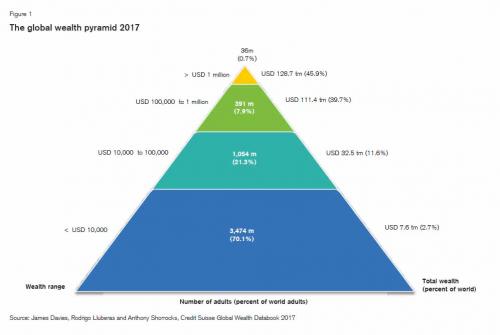

As Credit Suisse tantalizingly shows year after year (most recently one year ago), the number of people who control roughly half of the global net worth, or 45.9% of the roughly $280 trillion in household wealth, is declining progressively relative to the total population of the world, and in 2017 the number of people who were worth more than $1 million was just 36 million, roughly 0.7% of the world’s population of adults. On the other end of the pyramid, some 3.5 billion adults had a net worth of less than $10,000, accounting for just about $7.6 trillion in household wealth. And inbetween is the so-called global middle class – those 1.4 billion people whose rising anger at the status quo made Brexit and Trump possible. |

|

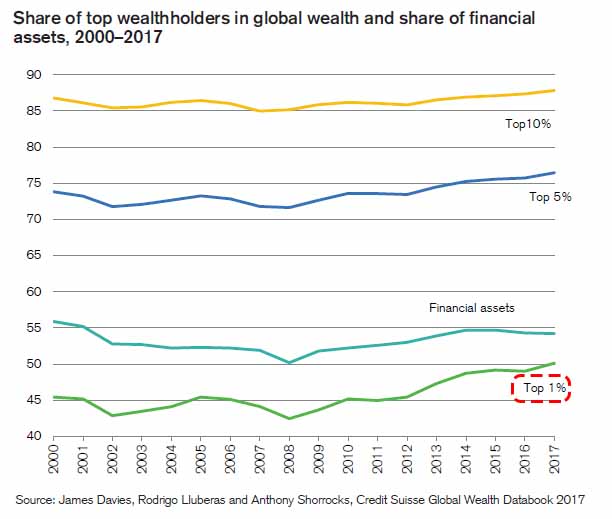

| As the report authors write, there is just one group to have benefited from the Fed’s post-crisis monetary policies: ” Our calculations show that the top 1% of global wealth holders started the millennium with 45.5% of all household wealth. This share was about the same until 2006, then fell to 42.5% two years later. The downward trend reversed after 2008 and the share of the top one percent has been on an upward path ever since, passing the 2000 level in 2013 and achieving new peaks every year thereafter. According to our latest estimates, the top one percent own 50.1 percent of all household wealth in the world.”

As the bank then laconically adds, “Global wealth inequality has certainly been high and rising in the post-crisis period.” And as the chart below shows, in 2017, for the first time ever, the richest 1% now controls just over half, or 50.1%, of global wealth. |

Top Wealthholders and Share of Financial Assets, 2000 - 2017 |

| To be sure, 2017 was a good year for the rich: it saw 2.3 million people becoming new dollar millionaires, with the total number of millionaires increasing to 36 million. “The number of millionaires, which fell in 2008, recovered fast after the financial crisis, and is now nearly three times the 2000 figure,” Credit Suisse said. The poorest 3.5 billion people, who account for 70 percent of the working age population, each earn less than $10,000 and account for just 2.7 percent of global wealth.

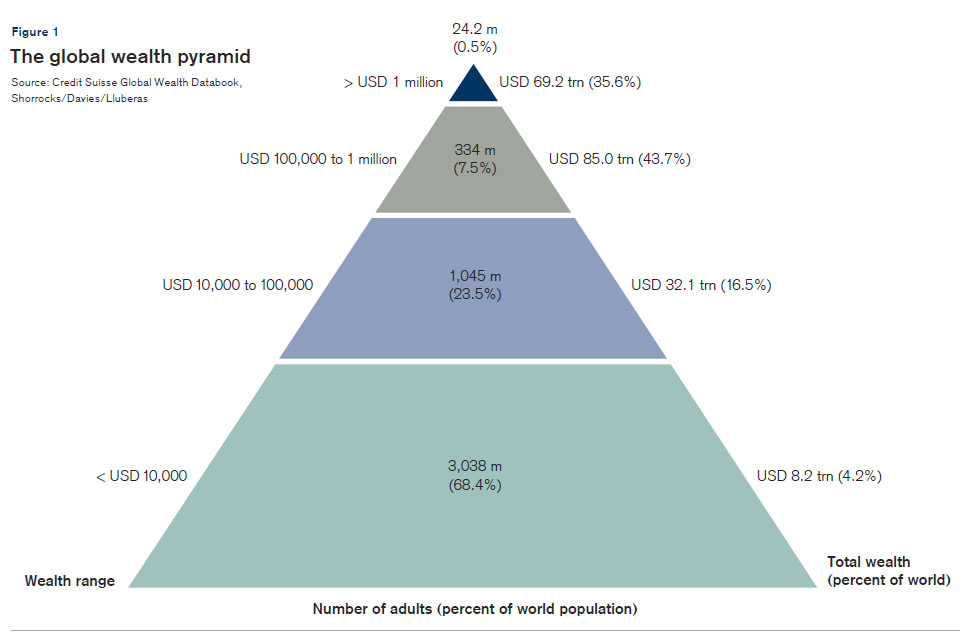

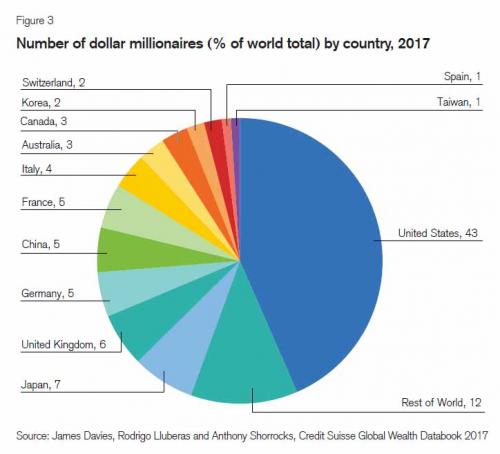

It’s only getting better… for the rich that is: with global wealth now at $280 trillion, this figure is expected to grow to over $340 trillion in five years. For those asking, you need to own $76,754 to be a member of the top 10% of global wealthholders and $770,368 to belong to the top 1%. The report said the poor are mostly found in developing countries, with more than 90% of adults in India and Africa having less than $10,000. “In some low-income countries in Africa, the percentage of the population in this wealth group is close to 100%,” the report said. “For many residents of low-income countries, life membership of the base tier is the norm rather than the exception.” Meanwhile at the top of what Credit Suisse calls the “global wealth pyramid”, the 36 million people with at least $1m of wealth are collectively worth $128.7tn. More than two-fifths of the world’s millionaires live in the US, followed by Japan with 7% and the UK with 6%. Incidentally, we tracked down the first Credit Suisse report we found in the “wealth pyramid” series, from back in 2010, where the total wealth of the top “layer” in the pyramid was a modest $69.2 trillion for the world’s millionaires. It has nearly doubled in the 7 years since then. Meanwhile, the world’s poorest have gotten, you got it, poorer, as those adults who were worth less than $10,000 in 2010 had a combined net worth of $8.2 trillion, a number which has since declined to $7.6 trillion in 2016 despite a half a billion increase in the sample size. Meanwhile, the layer right above, also known as the “middle class”, has gone exactly nowhere, with a net worth of just over $32 trillion. |

|

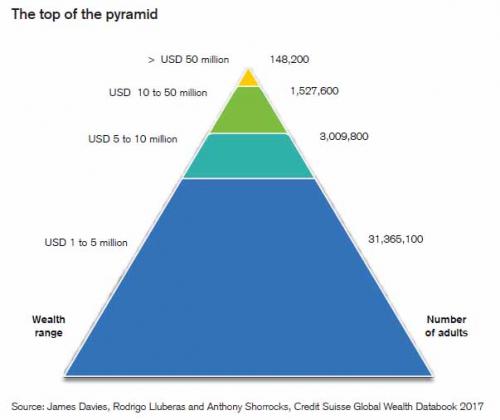

| How about the very top?

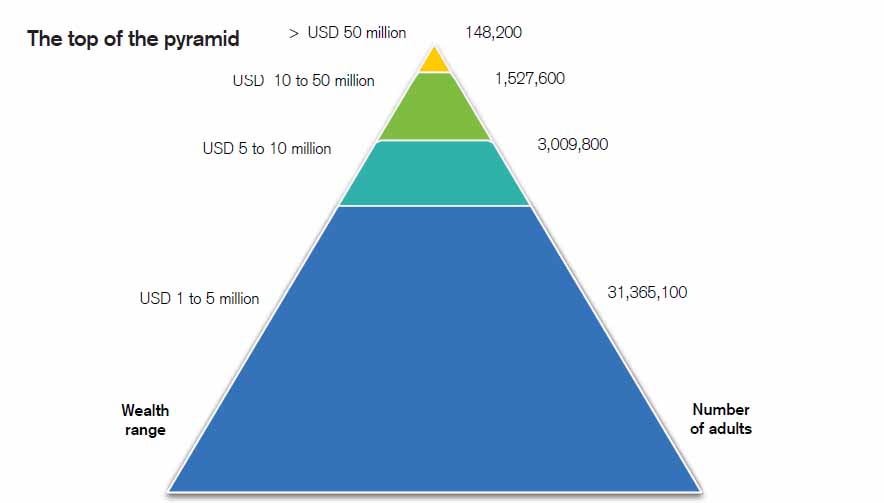

Things here are even more nuanced, with 31.4 million people whose net worth is between $1 and $5 million gradually tapering off to just 148,200 Ultra High Net Worth individuals who control more than $50 million in assets each. Of these, 54,800 are worth at least USD 100 million, and 5,700 have assets above USD 500 million. The total number of UHNW adults has risen by 13% (19,600 adults) during the past year, as a result of the widespread gains in wealth, primarily via artificially inflated rising financial assets, and the increase has been relatively uniform across all regions. |

|

| Here are some of the key excerpts from Credit Suisse

Wealth differences within and between countries Wealth differences between individuals occur for many reasons. Variation in average wealth across countries accounts for much of the observed inequality in global wealth, but there is also considerable disparity within countries. Those with low wealth are disproportionately found among the younger age groups who have had little chance to accumulate assets. Others may have suffered business losses or personal misfortune, or live in regions where prospects for wealth creation are more limited. Opportunities are also sometimes constrained for women or minorities. At the other end of the spectrum there are many individuals with large fortunes, acquired through a combination of talent, hard work and good luck. The wealth pyramid in Figure 1 captures these differences. The large base of low wealth holders supports higher tiers occupied by progressively fewer adults. We estimate that 3.5 billion individuals – 70% of all adults in the world – have wealth below USD 10,000 in 2017. A further 1.1 billion adults (21% of the global total) fall in the USD 10,000–100,000 range. While average wealth is modest in the base and middle tiers of the pyramid, the total wealth of these segments amounts to USD 40 trillion, underlining the economic importance of this often overlooked group. |

|

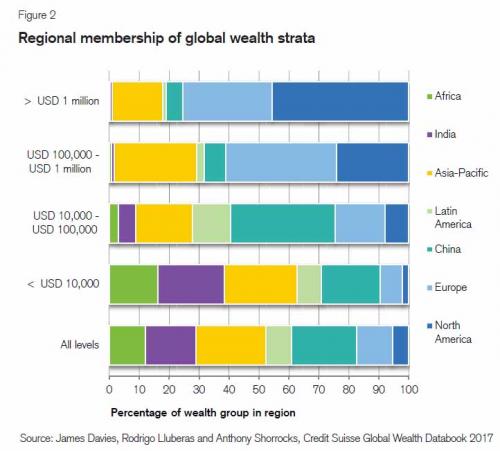

| The base of the pyramid

The layers of the wealth pyramid are quite distinctive. The base tier has the most even distribution across regions and countries (Figure 2), but also the widest spread of personal circumstances. In developed countries, about 30% of adults fall within this category, and for the majority of these individuals, membership is either transient – due to business losses or unemployment, for example – or a lifecycle phase associated with youth or old age. In contrast, more than 90% of the adult population in India and Africa falls within this range. In some low-income countries in Africa, the percentage of the population in this wealth group is close to 100%. For many residents of low-income countries, life membership of the base tier is the norm rather than the exception. |

|

| Mid-range wealth

In terms of global wealth, USD 10,000–100,000 is the mid-range band, covering 1.1 billion adults and encompassing a high proportion of the middle class in many countries. The average wealth of this group is quite similar to global mean wealth, and its combined net worth of USD 33 trillion provides it with considerable economic clout. India and Africa are under-represented in this segment, whereas China’s share is disproportionately high, having risen rapidly from 12.6% in 2000 to 35% in 2015, where it remains. This contrasts with India, which accounted for just 2.7% of the group in 2000, and only 5.7% now, less than half the share of China at the turn of the century before the rapid rise in its membership. The high wealth bands The top tiers of the wealth pyramid – covering individuals with net worth above USD 100,000 – comprised 6.1% of all adults in the year 2000. The proportion rose to 9.1% by the end of the financial crisis, before dropping back to the current level of 8.6%. Regional composition differs markedly from the strata below. Europe, North America and the Asia-Pacific region (omitting China and India) together account for 89% of the group, with Europe alone supplying 155 million members (36% of the total). This compares with just seven million members (1.7% of the global total) in India and Africa combined. The pattern of membership changes once again for the US dollar millionaires at the top of the pyramid. The number of millionaires in any given country is determined by three factors: the size of the adult population, average wealth, and wealth inequality. The United States scores high on all three criteria, and has by far the greatest number of millionaires: 15.4 million, or 43% of the world total (Figure 3). For many years, Japan held second place in the millionaire rankings by a comfortable margin – with 13% of the global total in 2011, for example, twice as many as the third placed country. However, the number of Japanese millionaires has fallen, alongside a rise in other countries. As a consequence, Japan’s share of global millionaires dropped to 10% in 2012, and has settled around 7%. This has been linked to a 16% decrease in its average wealth since 2011. |

|

| The United Kingdom retains third place with 6% of millionaires worldwide. Germany, China and France each account for 5% of the global total, followed by Italy with 4%, and Canada and Australia at 3%. Korea, Switzerland, Spain, and Taiwan are the remaining four countries hosting more than 360,000 millionaires, the minimum requirement for a one percent share of the global total.

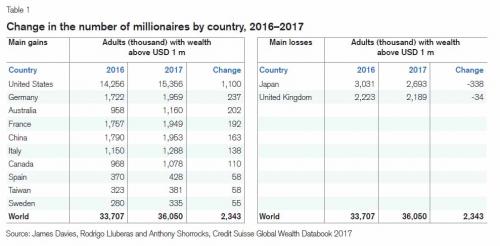

Changing membership of the millionaire group Year-on-year variations in the number of millionaires can often be traced to real wealth growth or exchange-rate movements. This year, widespread rises in wealth per adult have led to an additional 2.3 million dollar millionaires, almost half of whom (1.1 million) reside in the United States. Another 620,000 new millionaires are located in the main Eurozone countries (Germany, France, Italy and Spain) partly due to a 3% rise in the euro against the US dollar. Australia added 200,000 new members and about the same number appeared in China and India taken together. Millionaire numbers fell in very few countries, the main exceptions – all associated with depreciating currencies – being the United Kingdom, which lost 34,000, and Japan, which shed over 300,000. |

Change in the number of Millionaires, 2016 - 2017 |

| High net worth individuals

The primary sources of information on wealth distribution – official household surveys – tends to become less reliable at higher wealth levels.To estimate the pattern of wealth holdings above USD 1 million, we therefore supplement the survey data with information gleaned from the Forbes annual tally of global billionaires. These data are pooled for all years since 2000, and wellknown statistical regularities are then used to estimate the intermediate numbers in the top tail. This produces plausible values for the global pattern of asset holdings in the high net worth (HNW) category from USD 1 million to USD 50 million, and in the ultra-high net worth (UHNW) range from USD 50 million upwards. While the base of the wealth pyramid is characterized by a wide variety of people from all countries and all stages of the lifecycle, HNW and UHNW individuals are heavily concentrated in particular regions and countries, and tend to share similar lifestyles, for instance participating in the same global markets for luxury goods, even when they reside in different continents. The wealth portfolios of these individuals are also likely to be more similar, with a focus on financial assets and, in particular, equities, bonds and other securities traded in international markets. For mid-2017, we estimate that there are 35.9 million HNW adults with wealth between USD 1 million and USD 50 million, of whom the vast majority (31.4 million) fall in the USD 1–5 million range (Figure 4). There are 3.0 million adults worth between USD 5 million and USD 10 million, and another 1.6 million have assets in the USD 10–50 million range. Europe and North America had similar numbers of HNW individuals from 2007 to 2009, but North America then opened up a gap that has widened significantly since 2013. North America now accounts for 16.4 million members (46% of the total), compared to 10.8 million (30%) in Europe. Asia-Pacific countries, excluding China and India, have 6.1 million members (17%), and a further 2.0 million are found in China (5% of the global total). The remaining 1.2 million HNW individuals (2% of the total) reside in India, Africa or Latin America. |

|

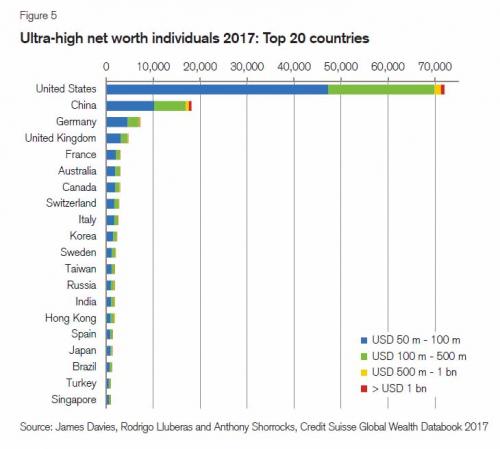

| Ultra-high net worth individuals

Our calculations suggest that 148,200 adults worldwide can be classed as UHNW individuals, with net worth above USD 50 million. Of these, 54,800 are worth at least USD 100 million, and 5,700 have assets above USD 500 million. The total number of UHNW adults has risen by 13% (19,600 adults) during the past year, as a result of the widespread gains in average wealth. All regions shared in this rise in the number of UHNW individuals. North America dominates the regional rankings, with 75,000 UHNW residents (51%), while Europe has 31,900 (22%), and 17,500 (12%) live in Asia-Pacific countries, excluding China and India. Among individual countries, the United States leads by a huge margin with 72,000 UHNW adults, equivalent to 49% of the group total (Figure 5), a rise of 9,900 compared to mid-2016. China occupies second place with 18,100 UHNW individuals (up |

Ultra-high Net Worth Individuals 2017 |

| The wealth spectrum

The wealth pyramid captures the contrasting circumstances between those with net wealth of a million US dollars or more in the top echelon, and those lower down the wealth hierarchy. Discussions of wealth holdings often focus exclusively on the top tail. We provide a more complete and balanced picture, believing that the middle and base sections are interesting in their own right. One reason is the sheer size of numbers and their political power. However, their combined wealth of USD 40 trillion also yields considerable economic opportunities, which are often overlooked. Addressing the needs of these asset owners can drive new trends in both the consumer and financial industries. China, Korea and Singapore are examples of countries where individuals have risen rapidly through this part of the wealth pyramid. India has shown less progress to date, but has the potential to grow rapidly in the future from its low starting point. While the middle and lower levels of the pyramid are important, the top segment will likely continue to be the main driver of private asset flows and investment trends. Our figures for mis-2017 indicate that there are now nearly 36 million HNW individuals, including 2.0 million in China, and 6.3 million more in India and other Asia-Pacific countries. At the apex of the pyramid, 148,200 UHNW adults are each worth more than USD 50 million. This includes 18,100 UHNW individuals in China (12% of the global total), nearly 40 times the number at the turn of the century. A further 6,400 UNHW adults (4% of the total) can be found in Taiwan, India, Hong Kong and Singapore. |

The Top of the Pyramid |

Tags: Asia Pacific,Australia,China,Credit Suisse,Economic inequality,economy,Eurozone,federal government,Financial crisis of 2007–2008,France,Germany,Hong Kong,India,Italy,Japan,Latin America,newslettersent,Switzerland,Unemployment,United Kingdom