Authored by John Mauldin via MauldinEconomics.com,

Switzerland is a small country of just 8 million people, but they make an outsized impact on economics and finance and money.

Switzerland is a small country of just 8 million people, but they make an outsized impact on economics and finance and money.

Because Switzerland is considered a safe haven and a well-run country, many people would like to hold large amounts of their assets in the Swiss franc. This makes the Swiss franc intolerably strong for Swiss businesses and citizens.

So the Swiss National Bank (SNB) has to print a great deal of money and use nonconventional means to hold down the value of their currency. Their overnight repo rate is -0.75%.

Switzerland Is Buying US Stocks on an Enormous Scale

And the SNB is buying massive quantities of dollars and euros, paid for by printing hundreds of billions in Swiss francs.

The SNB owns about $80 billion in US stocks today (June, 2017) and a guesstimated $20 billion or so in European stocks (this guess comes from my friend Grant Williams, so I will go with it).

They have bought roughly $17 billion worth of US stocks so far this year. And they have no formula; they are just trying to manage their currency.

Think about this for a moment: They have about $10,000 in US stocks on their books for every man, woman, and child in Switzerland, not to mention who knows how much in other assorted assets, all in the effort to keep a lid on what is still one of the most expensive currencies in the world.

Switzerland is now the eighth-largest public holder of US stocks. It has got to be one of the largest holders of Apple.

What Happens When There Is a Bear Market?

Who bears the losses?

Print just more money to make up the difference on the balance sheet? Do we even care what the Swiss National Bank balance sheet looks like? More importantly, do they really care?

We all remember European Central Bank President Mario Draghi’s famous remark, that he would do “whatever it takes” to defend the euro. We could hear the Swiss singing from the same hymnbook soon.

Central Banks and Governments Exacerbate the Bubble

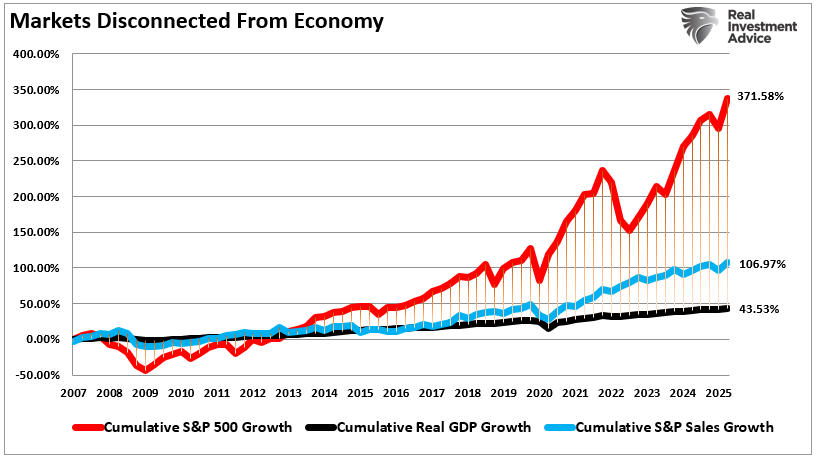

The point is that central banks and governments are flooding the market with liquidity all over the world.

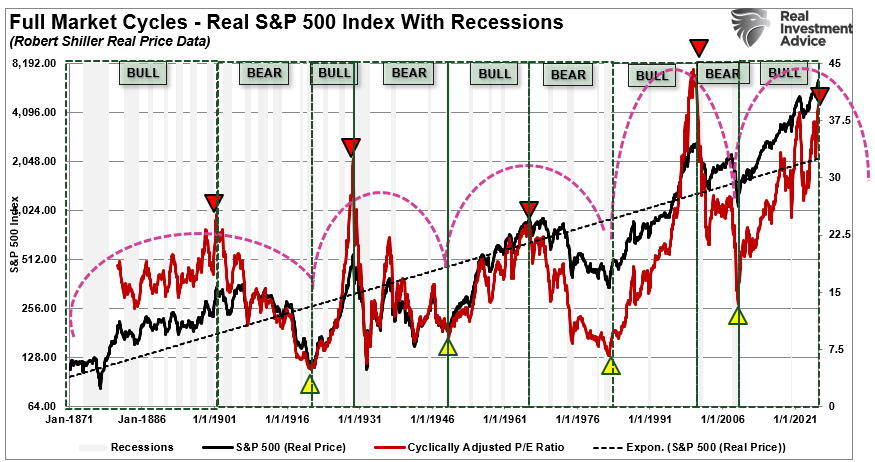

That’s showing up in the private asset markets, in stock and housing and real estate and bond prices. It creates an unquenchable desire for what appear to be cheap but are actually overvalued assets—which is what creates a Minsky moment.

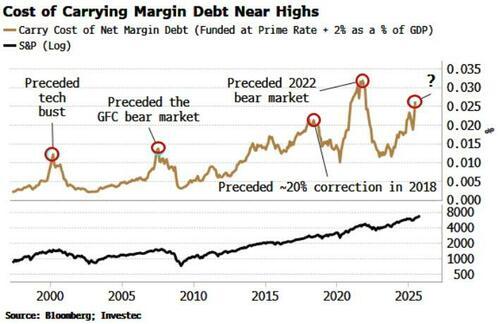

Now, remember what Minsky said: When an economy reaches the Ponzi-financing stage, it becomes extremely sensitive to asset prices. Any downturn or even an extended flat period can trigger a crisis.

While we have many domestic issues that could act as that trigger, I see a high likelihood that the next Minsky moment will propagate from China or Europe. All the necessary excesses and transmission channels are in place.

The Great Reset Is Close

The hard part, of course, is the timing. The Happy Daze can linger far longer than any of us anticipate. Then again, some seemingly insignificant event in Europe or China—an Austrian Archduke’s being assassinated, or what have you—can cause the world to unravel.

It’s a funny world.

Our central banks and governments exhibit unmistakable herd behavior and continue to do the same foolish things over and over. They never really intend to have the crisis that ensues.

Remember Farrell’s Rule 3: There are no new eras. The world changes, but danger remains. Gravity always wins eventually. It will win this time, too. And when it does, we will begin to undergo the Great Reset.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Apple,Banking in Switzerland,Bear Market,Bond,Central Bank,central banks,China,Currency intervention,economy,European central bank,Finance,Financial services,newslettersent,Real Estate,Swiss Franc,Swiss National Bank,Switzerland

1 comments

Stefan Wiesendanger

2017-07-10 at 13:59 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Mauldin like many foreign observers believe that the SNB is creating liquidity (“printing” money) to buy foreign assets in order to depress the currency. This is a very partial view.

In the total picture, Switzerland is a country of hard-working savers whose savings traditionally finance the world. Hence the large net international investment position (NIIP) of 130% of GDP (or approx. 100’000 USD per capita, 2016).

Since 2007, Swiss savers (indiviuals, corporations and institutions) have sought to bring home a part of their claims on foreign assets for a number of reasons (the gross international investment position is about 4.5trn USD, 2016). This means in practice that they are selling foreign titles against Swiss Francs.

All the SNB does is to accommodate this inflow by taking the foreign titles on their balance sheet against new Swiss Francs. The assumption is that this is a temporary situation and that Swiss savers will return to their traditional role of finaning the world eventually.

Of course it is true that the SNB assumes the foreign-exchange and market risks while these foreign assets are stored (temporarily) on its balance sheet. But it charges a fee for these services – this is the negative interest rate.

From these considerations, it becomes clear that the SNB is not injecting any excess liquidity into the global monetary system. Rather, it is absorbing part of the excess liquidity, which is quite the contrary. Also, the finanical liquidity it is absorbing has been previously earned through REAL savings by Swiss entities. This also is quite the contrary of the idea that the SNB creates buying power “out of thin air”.

Finally, it seems quite reasonable that as a custodian bank of Swiss private entities’ foreign claims, 20% of the assets are invested in stocks (of which half are US stocks). From a value and a risk perspective, the share of real assets should be much higher than 20%! The only reason they are not are for liquidity considerations – the SNB must be able to liquidate their assets at any time as soon as Swiss entities return to their normal financing role, by taking their Swiss Francs (which they now hold inactively) abroad again.