Thirty Year RetreadWhat will President Trump and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe talk about when they meet later today? Will they gab about what fishing holes the big belly bass are biting at? Will they share insider secrets on what watering holes are serving up the stiffest drinks? [ed. note: when we edited this article for Acting Man, the meeting was already underway] Indeed, these topics are unlikely. Rather, what they’ll be discussing is cooperative trade, growth, and employment policies between their respective national economies. They’ll also talk about currency debasement opportunities. Soon enough, perhaps by the time you read this, you’ll be able to peruse the headlines and garner soundbites of their discussions. Maybe a new partnership will be announced. Anything’s possible. Regardless, what follows is a brief review – a thirty year retread – that’s intended to put the meeting within its proper context. This is the back story you won’t hear anywhere else… To begin, it was precisely the wrong thing to do at precisely the wrong time. But that didn’t stop the best and the brightest from attempting to improve upon the natural order of things. |

|

| By 1985, fourteen years after Nixon severed the last tattered threads tying the dollar to gold, floating currencies had resulted in grotesque distortions to the global economy. Clever fellows were called upon to remake the world in their image.

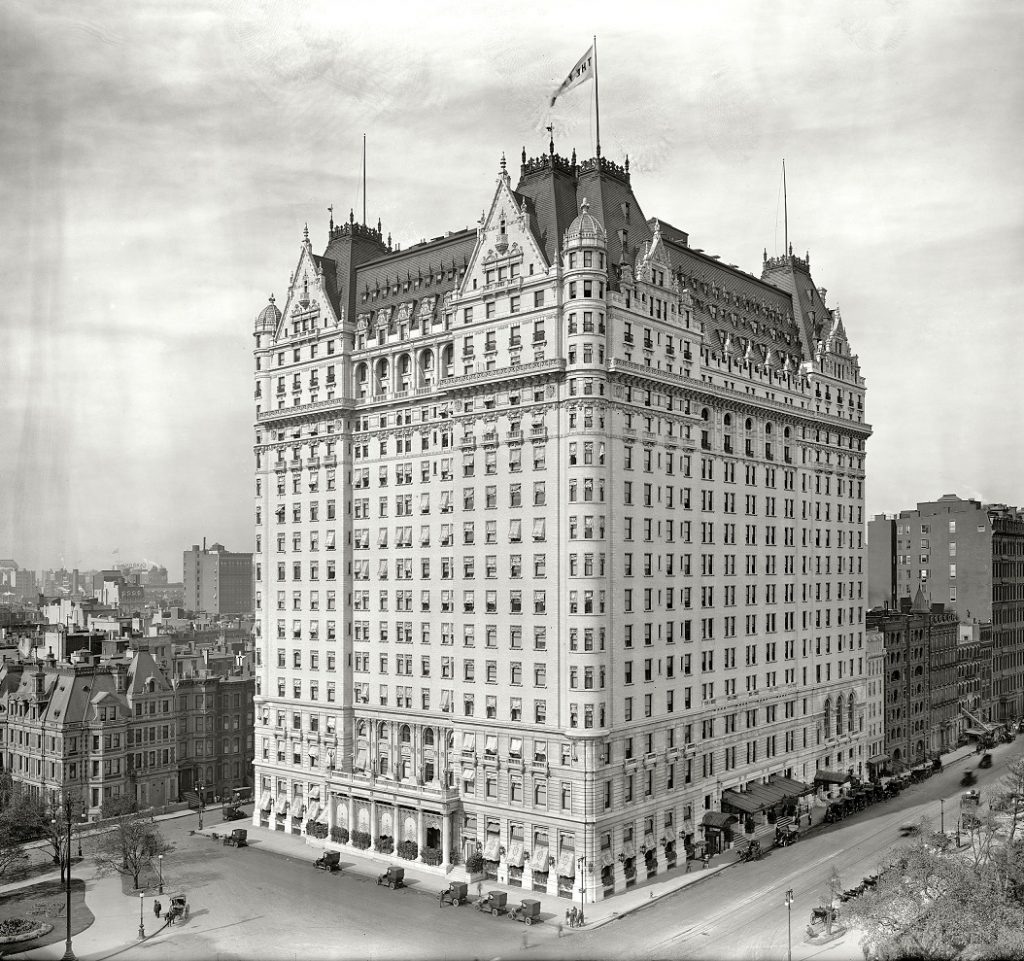

As far as we can tell, none of the officials from West Germany, France, the United States, Japan, and the United Kingdom, who gathered at New York’s Plaza Hotel on September 22, 1985, knew they were letting another genie out of the bottle. |

|

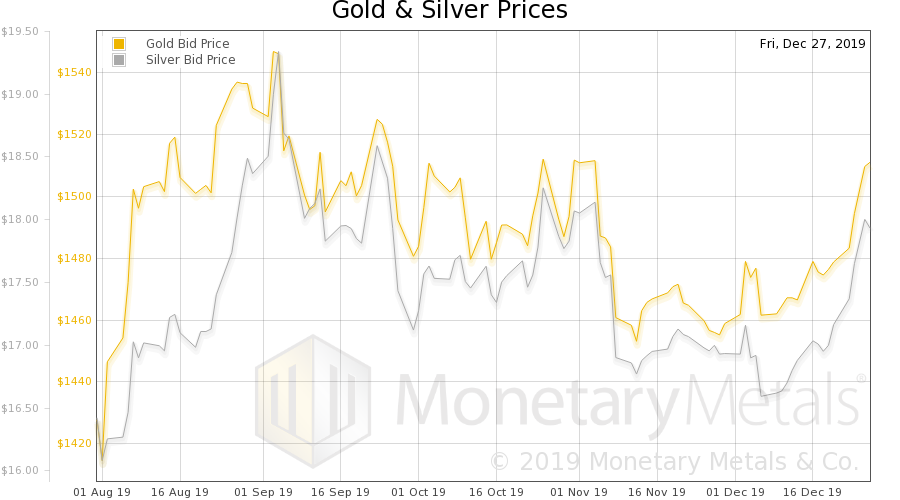

| The U.S. dollar had appreciated 50 percent between 1980 and 1985 against the Japanese yen, West German Deutsche Mark, and British pound – the currencies of the next three largest economies at the time.

Not unlike today, American manufacturers said they couldn’t compete with the dollar valued so much higher than the currencies of America’s trading partners. In addition, the U.S. trade deficit had ballooned to 3.5 percent of GDP as foreign imports became vastly cheaper for American consumers. No doubt, a new policy fix was in order. |

The players who hatched out the Plaza accord in 1985. It didn’t take long for the then still relatively new system of floating fiat currencies to provoke one intervention after another. From left to right: Gerhard Stoltenberg of West Germany, Pierre Bérégovoy of France, James A. Baker III of the United States, Nigel Lawson of Britain, and Noboru Takeshita of Japan. Photo credit: Fred R. Conrad - Click to enlarge |

One Ominous SignThe Plaza Accord sought to devalue the dollar to bring global trade back into balance. More importantly, the Plaza Accord was the first time central bankers executed a coordinated intervention into foreign exchange markets, where the global economy took prominence over national sovereignty. By all policy maker accounts, the Plaza Accord was a great success. The dollar declined by 51 percent against the yen between 1985 and 1987, as intended. In fact, in early 1987 these countries met again, this time in Paris, to stem the dollar’s further decline. |

US Dollar Index, Weekly DXY, weekly, 1980 – 1988. Regarding the Plaza accord, note that these geniuses met when the new downtrend in the dollar was already several months old and well established. On Saturday October 17 1987, treasury secretary James Baker called the German minister of finance and demanded from him to force the BuBa to rescind its most recent rate hike. He then threatened that the US would unilaterally devalue the dollar even further if the German authorities failed to comply. On the following Monday, the stock market crashed by 22%, to this day the biggest one day plunge in history - Click to enlarge |

| The resulting Louvre Accord allowed the Bank of Japan to freely supply yen for dollars. Magnificent, unintended consequences soon bubbled up in Tokyo.

The recessionary effect of a strengthening yen and the subsequent Louvre Accord fueled Japanese money and credit growth. These expansionary monetary policies resulted in the massive Japanese asset price bubble of the late 1980s and long multi-decade deflation after the bubble popped. For instance, in 1989 property in Tokyo’s Ginza district sold for $20,000 per square foot. By 2004 prices had fallen over 90 percent. The stock market bubble and bust was equally absurd… In September 1985, at the time of the Plaza Accord, the Nikkei 225 traded for about 12,667. By December 29, 1989, the Nikkei 225 closed at 38,916 – up over 207 percent. Presently, the Nikkei 225 is at about 19,300 – down over 50-percent even more than 27-years later. |

Nikkei 225 Index, Monthly The Nikkei, 1987 – today. “Buy stocks for the long term”, they said. “Never, ever sell”, they said, “that’s always a mistake”. When the Nikkei peaked at the end of 1989, its average trailing P/E ratio was over 80. No other broad-based big cap index in a large developed market has ever reached such a nosebleed valuation (SPX in 2000: trailing P/E of 44). In 2008, almost 20 years after the bubble’s peak, the Nikkei traded well below 8,000 points, a decline of approximately 81%. It remains 50% below its 1989 peak even today, after a 160% rally from its low - Click to enlarge |

| The unfortunate souls who bought stocks in December of 1989 and held on to them will see most of their adult lives pass by before getting back to even – if ever.

After Japan’s asset prices blew up, Japan’s economy went into a multi-decade slump. Despite mammoth amounts of government stimulus and deficit spending, pioneering experiments in quantitative easing, direct stock market purchases via ETFs, negative interest rates, and more, Japan’s economy has never achieved “escape velocity”. Of course, no one could have known in 1989 how long this slump would last. But early on, for the shrewd observer, there were gloomy warning signs for everyone to see… For example, on January 8, 1992, following the mass decline of Japan’s protracted credit induced asset bubble, President George H.W. Bush, while visiting in Japan, leaned over to Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa. Presumably, Bush intended to whisper some vital Yankee secrets for orchestrating a financial bailout. But, then, in an ominous and profound sign of things to come, he barfed on his lap. Japan’s economy has yet to recover. |

The infamous “bad sushi” moment – shortly after Japan’s prime minister Myazawa’s crotch is bathed in a generous helping of elder Bush vomit, the latter’s wife jumps at the chance to get rid of her husband by suffocating him with a napkin. Vigilant secret service agents enter the fray and prevent the assassination attempt from succeeding. As always, they remain unsung. |

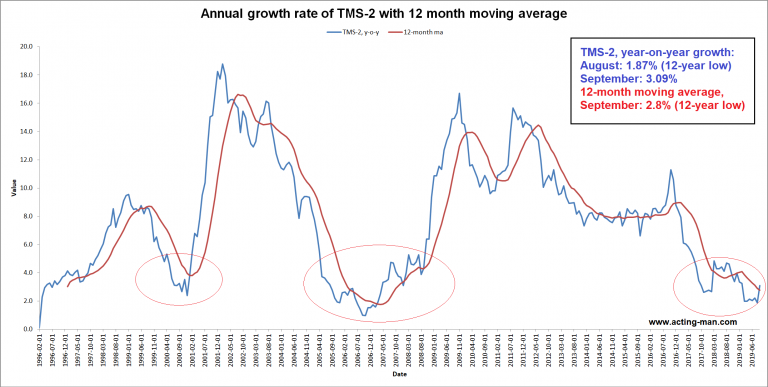

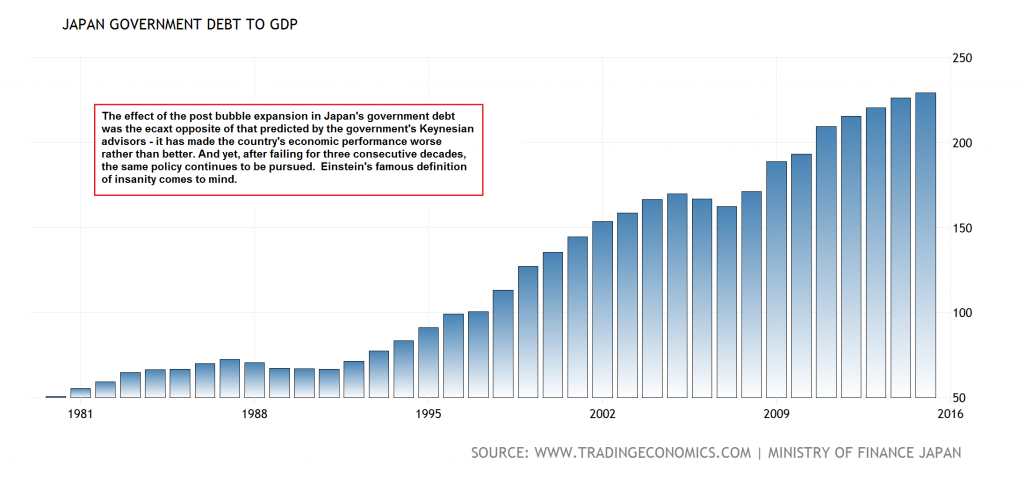

When Trumponomics Meets AbenomicsIn effect, Japan’s economy has continued to throw up all over itself. If you didn’t know, Japan’s government debt is 230 percent of GDP, which is the largest debt to GDP percentage of any industrialized nation in the world. By comparison, the government debt to GDP ratio of the United States is 104 percent. |

Japan Government Debt to GDP Drowning in debt: since the bursting of the great bubble, successive Japanese governments have implemented the Keynesian recipe to a T. The country has absolutely nothing to show for it, except the largest debtberg in the developed world. This is easily one of the most expensive government boondoggles in history - Click to enlarge |

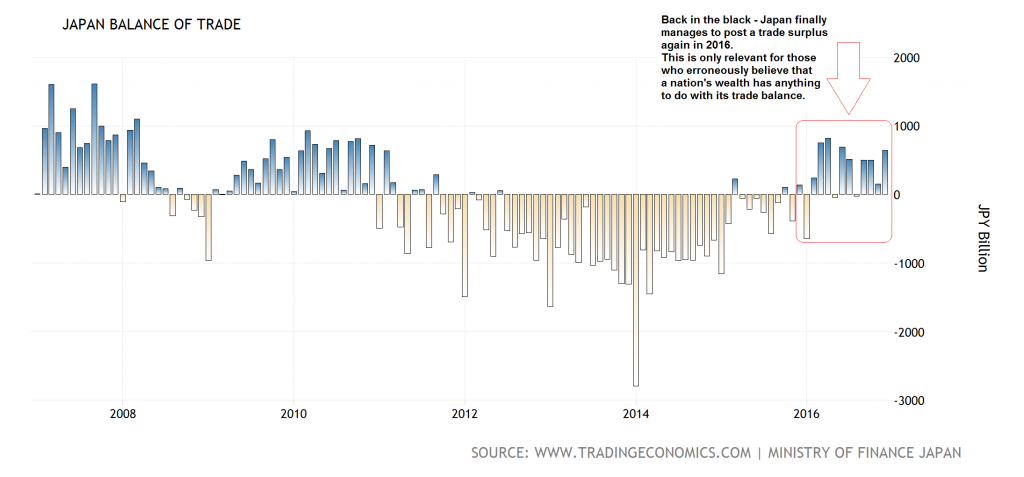

| However, contrary to the United States, Japan has financed its debt domestically. The way Japan has been able to get by without borrowing from foreigners is through its positive trade balance. With the exception of 2012 through 2015, Japan has consistently exported more than it imported. Last year, Japan’s trade surplus widened 361.6 percent to JPY 641.4 billion as of December of 2016.

If you recall, Prime Minister Abe, the brainchild behind the Bank of Japan’s Abenomics, has pursued a reckless policy to boost exports by trashing the currency. A weak yen, Abe believes, should give Japan a competitive advantage. By devaluing the yen, Abe believes Japan should somehow be able to export its way to wealth. Who knows, maybe Abenomics is working – for now? Japan has been able to move its trade balance back into the black. Nonetheless, the cost of devaluing the population’s wealth will ultimately outweigh any short term economic gains. In the meantime, the long-term trade deficit the United States has had with Japan causes steam to come out of President Trump’s ears. It goes counter to the objectives of Trumponomics. Rather than importing goods made in Japan, Trump wants to return the jobs back to the U.S. and then export goods. Hence, when they meet today, he’s looking to cut a deal with Prime Minister Abe like he’s cut deals in the past with New York cement contractors. “You scratch my back, I’ll scratch yours.” But what deal is there that can really be cut? A Plaza Accord Part II is a nonstarter. But there are other ideas we’ve come across. One idea is for Japanese companies to invest in Trump’s infrastructure projects. Another idea is for Japan to increase energy imports from the U.S. Will such agreements work? Will they bring wealth to both the U.S. and Japan? Your guess is as good as ours. What is known is that today’s predicaments, manifesting in ridiculous trade imbalances, are the consequences of unbacked fiat money. Things have gone absolutely haywire in the absence of natural limits. Certainly, in the futile effort to correct the distorted trade imbalance, the meeting of Trumponomics with Abenomics will make an ample contribution to the madness. You can damn near count on it. |

Japan Balance of Trade, 2008 - 2016 After impoverishing Japan’s citizens by devaluing their currency’s external value, Japan finally achieves a trade surplus again. Unfortunately, a trade surplus is completely irrelevant as a measure of prosperity. Obviously, no country has ever devalued itself to riches. Not to put too fine a point to it, the mercantilist doctrines favored by both Japan’s post WW2 governments and Mr. Trump are long-refuted utter hogwash. Why do these nonsensical policies remain so popular? We suspect a mixture of economic ignorance and the desire to serve special interests is at work - Click to enlarge |

Charts by: StockCharts, BigCharts, TradingEconomics

Chart and image/video annotations and captions by PT

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: newslettersent,On Economy,On Politics