Many observers continue to tout Italian risks as the greatest in the euro area into the year end. The constitutional referendum that would emasculate the Senate, and end the perfect bicameralism that has contributed to more than 60 governments since the end of WWII.

Many observers continue to tout Italian risks as the greatest in the euro area into the year end. The constitutional referendum that would emasculate the Senate, and end the perfect bicameralism that has contributed to more than 60 governments since the end of WWII.

The fact that Prime Minister Renzi indicated he would resign if the referendum did not pass highlighted the political risk. The second largest party in Italy after Renzi’s PD coalition is the Five-Star Movement which wants to leave the monetary union.

However, judging from various news accounts and the social media, it has largely been missed that Renzi has backtracked from this. He has indicated the linkage was an error and that regardless of the results of the referendum, the next parliamentary election would take place as scheduled in 2018. Italy’s Interior Minister, who does not hail from Renzi’s PD, confirmed that the government would not resign if the referendum lost. Just like Italy is not Greece, Renzi is not Cameron. To be sure, the loss of the referendum could be seen as a sign that Renzi’s reform efforts have stalled. It could weaken him, but the that is not the same as toppling him. The contagion emanating from Italian politics is less than was the case say three months ago, though it may not be widely recognized yet by global investors.

Portugal does not pose systemic risk, but there may be contagion to Spanish banks that have exposure and Italian assets that often appear correlated to risk assets. The way access to the ECB facilities works is that a country needs at least one of the top four rating agencies to recognize it as investment grade credit. That is the case for Portugal, where only DBRS sees the sovereign as investment grade.

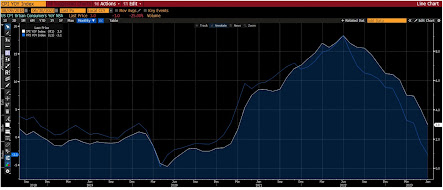

DBRS is set to review Portugal’s credit rating on October 21. It has expressed concern about rising yields and the fragility of the recovery. The sovereign-bank link has not been severed. Portuguese banks are large holders of its sovereign bonds (35 bln euros at the end of July). The combination of weak growth and rising yields means that Portugal’s debt/GDP cannot stabilize. Portugal’s debt/GDP is roughly 136%, trailing Italy (142%) and Greece (185%) in Europe.

DBRS has a stable rating for Portugal. It could still cut the rating, but it is unlikely. Barring a shocking development, the first step is to change the outlook. This alone could spur some additional pressure. The market, however, has shunned Portugal bonds. The benchmark 10-year yield has risen 42 bp over the past three months. A similar tenor Greek bond yield has risen 35 bp. Spain’s benchmark yield has fallen 16 bp, while Italy’s is up nine bp. Year-to-date Portugal’s performance is even more extreme. The yield is up 92 bp, while Spain is off 75 bp and Italy off 25 bp. Greece’s 10-year yield is up 25 bp since the start of the year.

If DBRS does take away Portugal’s investment grade rating, there would be significant implications. Portuguese banks, which are heavier users of ECB facilities, could no longer use government bonds as collateral, without a waiver from the central bank. Its bonds would no longer qualify under the ECB’s sovereign bond purchase program. Portuguese banks could be forced, like Greek banks to rely on credit from the national central bank (Emerging Lending Assistance).

Although a loss of Portugal’s investment grade status is not the most likely scenario, the contagion effect could be significant. It comes at a time, where domestic political considerations, especially in Germany, would leave little room to maneuver. A new assistance program cannot be ruled out.

Many observers continue to tout Italian risks as the greatest in the euro area into the year end. The constitutional referendum that would emasculate the Senate, and end the perfect bicameralism that has contributed to more than 60 governments since the end of WWII.

Many observers continue to tout Italian risks as the greatest in the euro area into the year end. The constitutional referendum that would emasculate the Senate, and end the perfect bicameralism that has contributed to more than 60 governments since the end of WWII.