Last week’s decline in stock markets was probably caused by the HSBC manufacturing PMI for China that contracted for the first time in months, and possibly also by the rapid fall of UK unemployment rates and Bank of England’s response to it. As the rising gold price showed, Fed “tapering fears” were not at the heart of the sell-off.

The more than two-year rally in the stocks of developed markets (DM) is assisted by the “glorious combination” of:

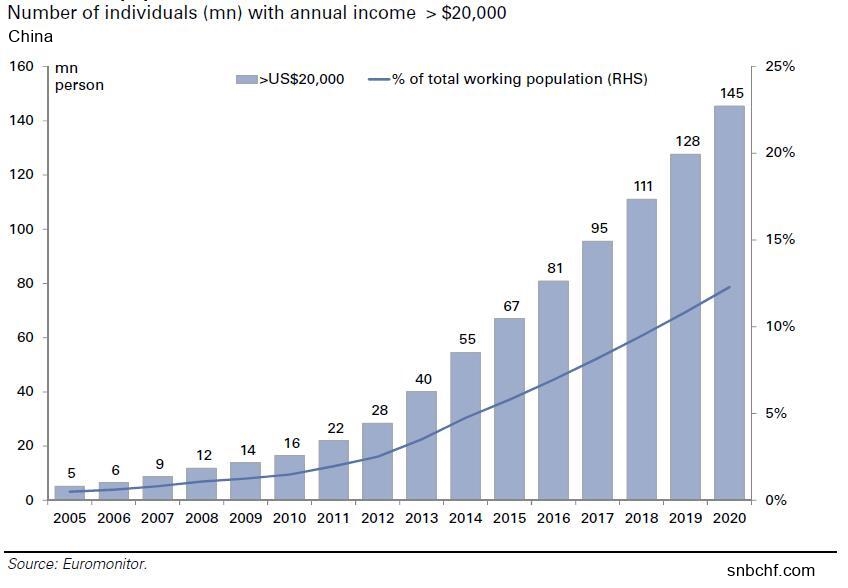

Continuing global consumption, mostly driven by rising income and demand in emerging markets (EM), plus somewhat recovering demand in advanced economies.

Continuing global consumption, mostly driven by rising income and demand in emerging markets (EM), plus somewhat recovering demand in advanced economies.- The recovery in the United States, that is not too fast to create inflation or stop cheap money. New payrolls in 2013 (2.22 million) were lower than in 2012 (2.27 million) and lower than in 2011 (2.42 million).

- Nearly stagnating wages and low inflation in developed markets due to high unemployment – e.g. Europe – and weak participation rates in the U.S.

- Higher company profits in DM thanks to the reduction of costs in the form of stagnating wages, improving processes and technology.

Precisely due to falling British unemployment, high spending and a persistent trade deficit, the FTSE was one of the worst 2013 performers in developed markets.

Precisely due to falling British unemployment, high spending and a persistent trade deficit, the FTSE was one of the worst 2013 performers in developed markets.

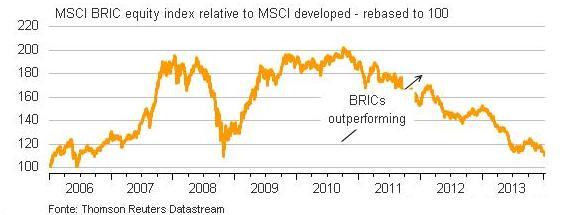

On the other side, currencies and stock markets of emerging markets were receding because the combination of EM consumption and wage rises weakens competitiveness and increases current account deficits.

The weak Chinese PMI let many investors stop believing in factor 1, in the continuing global demand; the rapid fall of British unemployment rates let them doubt factor 3 and assume that (at least) British wages and inflation might rise soon.

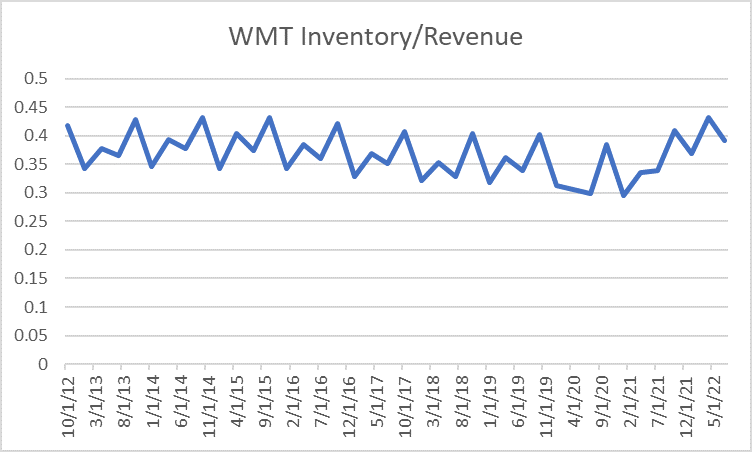

Weaker spending in Emerging Markets might squeeze company profits in Developed Markets

Investors, however, forget that a weaker currency, e.g. in emerging markets, typically leads to inflation, lower spending and higher savings, a long-discussed point in our blog in connection with potential euro exits. Central banks in EM are forced to raise rates which again weakens spending and GDP growth. Higher savings help to increase investments and current account surpluses and to overcome missing foreign investment inflows.

As the Japanese case shows, having a weaker currency does not directly imply a better current account balance; thanks to long-accumulated savings of previous years, the (aging) Japanese currently have the weakest savings rate in the developed world. People in EM, however, do not have this security cushion. They will not continue spending when due to a weak currency, inflation is higher than their wage hikes. Brasilian consumer confidence, for example, has fallen back to 2010 levels. On the other side, a weak currency may strengthen company profits in global comparison.

In summary, missing EM demand may weaken DM stocks. As Marc Chandler notes below, EM stock markets were among the best performers during last week’s sell-off. Hence rising DM demand may strengthen EM stocks. Moreover, due to missing EM spending we think that IMF growth projections for EM – 5.1% in 2014 vs. 4.7% in 2013 – are far too optimistic. Assuming 2.2% growth for DM is optimistic, too, given that many U.S: households and the ones in Southern Europe are still balance-sheet constrained.

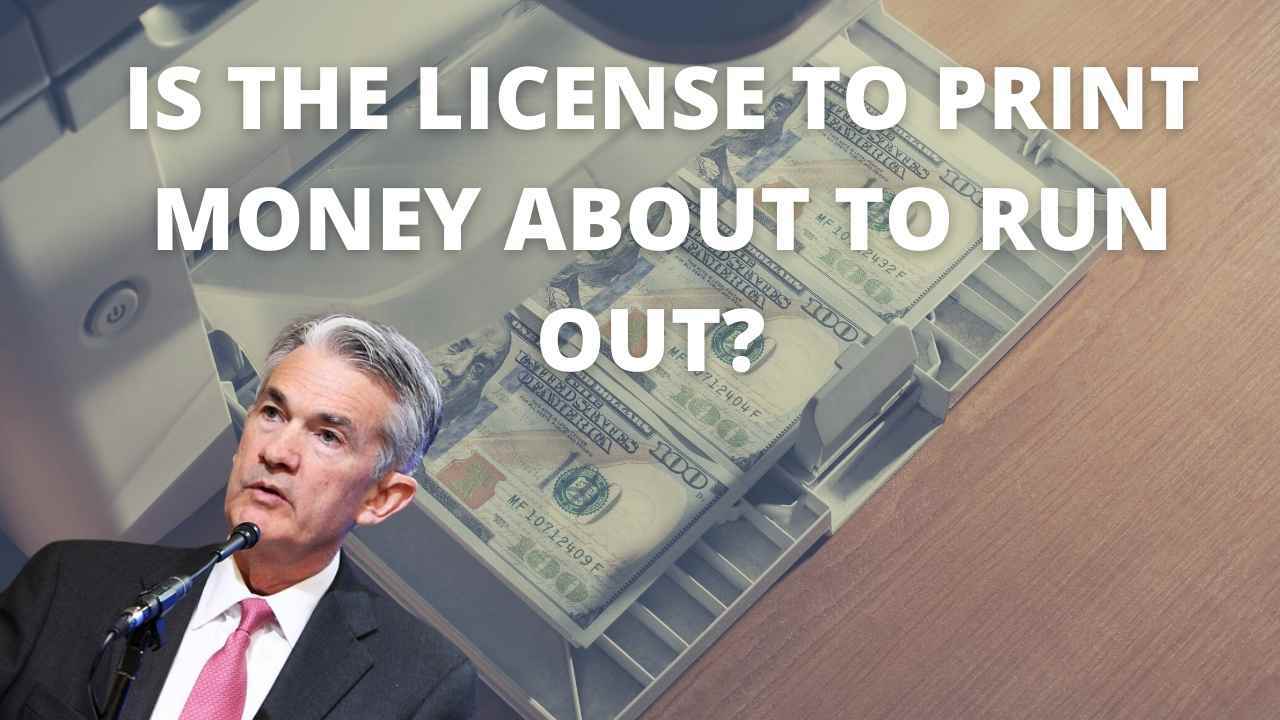

Fed’s tapering, tightening of EM central banks and (unnessary) investors’ fear imply that liquidity is missing there where it is needed – in emerging markets. The effects of tight monetary policy and continuing fear will be slow global growth.

George Dorgan

More about last week’s sell off by Marc Chandler’s http://www.marctomarket.com:

Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

The global capital markets imploded in the second half of last week and investors spent the weekend contemplating the significance. The main focus was on the emerging markets, which were especially hard hit. American-firsters (the tendency on the political right and left to blame the US first for all the undesirable things that happen in the world) jumped at the opportunity. Even in the Financial Times, which acknowledged other factors at work deemed worthy of a call out that the “Exit of money from Argentina has been driven by renewed concern about the US Fed”. Really?

That concern ostensibly is that the Fed is going to proceed with its tapering strategy announced last month. As the Fed reduces its yield compression efforts (QE), interest rates are expected to rise and making those emerging market countries reliant on foreign capital inflows (current account deficit countries) particularly vulnerable. We have seen in this in the recent past. Emerging market crisis have often happened when the Fed tightened. It is happening again. Q.E.D. Any further analysis has been rendered superfluous.

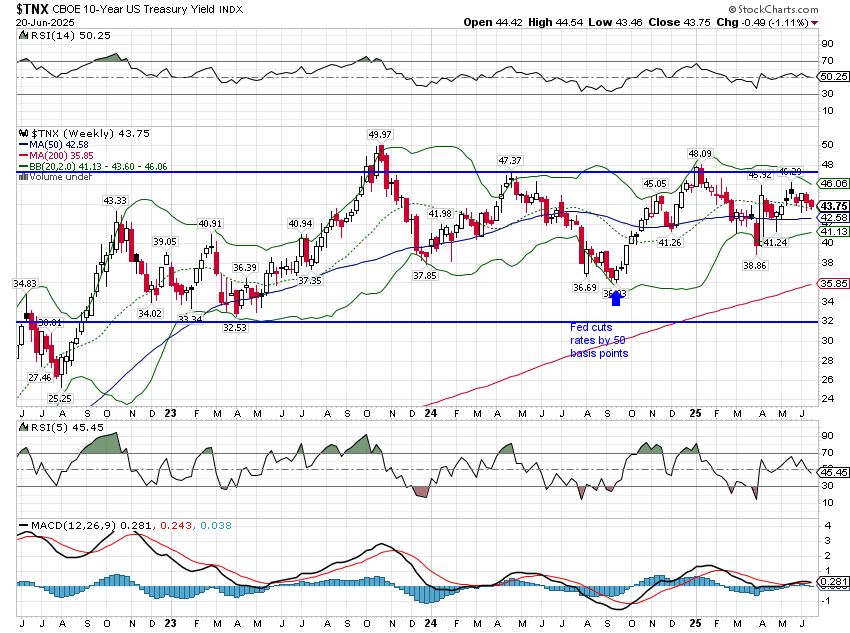

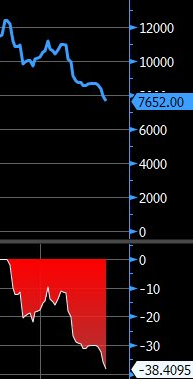

Rather than deduce the recent crisis from such rules, a quick reality check suggests a far more complicated picture. Moreover, the fact of the matter is the US interest rates have fallen not increased so far this year. Since peaking near 3.05% at the very start of the month, the US 10-year yield slipped 20-25 bp even before the equity market slide in the second half of last week. The short-end of the curve has been steadier, with the 2-year yield off about 4 bp this month. The short-dated T-bills have come under some pressure amid increased anxiety over the debt ceiling deadline and discordant rhetoric from Washington.

There are two levels of analysis that are relevant in a proper analysis: international and national. The international level of analysis would note other forces beside the Fed tapering. Four are in fact readily apparent. Two of them relate to China.

First, the HSBC flash manufacturing PMI was below the 50 boom/bust level, warning that economy is still slowing. Many emerging markets have grown on the back of China’s growth. Brazil and South Africa, for example, appear particularly sensitive to such a development. Second, there is heightened fear that China may accept the failure of a wealth management product that is thought to expire at the end of the month, just before the Lunar New Year, which is also absorbing liquidity.

Some fear a slippery slope, where one failure would be the spark panic in a situation fraught with moral hazard. Wealth management products appeared to offer investors significantly higher short-term yield than available in the market and seemingly guaranteed by the big bank distributors

The third international pressure on emerging markets came from pressure to unwind yen (and to some extent Swiss franc) cross positions. Many leveraged participants were using the yen as a financing currency to fund the purchase of some emerging markets. As the Commitment of Traders report from the CME currency futures show, the short yen position was extreme. Ironically, the decline in US Treasury yields may have helped spark the yen short squeeze that forcing players out of the long end of the position.

The fourth international factor involves the increasing reliance of central banks on forward guidance. Comments by BOE Governor Carney and one of the acknowledged innovators of forward guidance, suggested that it was GTC (good-til-close).

Some saw in Carney’s comments an abandonment of forward guidance. Contagion was a word thrown around last week in terms of price action, but questions raised by Carney’s comments put the Fed’s forward guidance under question as well. It seemingly removed an anchor of monetary policy.

We have argued that the confidence of the Fed’s forward guidance was on fragile footing. First, it was announced by a Fed chairman that was not going to implement it. Second, Obama and Bernanke have done nearly everything one would advise if one wanted to prevent Yellen from exerting strong leadership: have her predecessor lay out, in some detail, the path of the Fed for the next year; do not have Bernanke resign upon Yellen’s confirmation; and nominate as the vice-chairman a person whose track record of accomplishments and experience cannot help buy overshadow the Yellen.

After Obama’s first choice to succeed Bernanke (Summers) was not successful, the President had little choice but to accept Yellen. His reluctance seems painfully obvious and we suspect to the detriment of investor confidence.

We have argued that forward guidance is a communication style that is simply being emphasized now, as central banks (except for the BOJ) move away from unorthodox policies. Just as the Fed tried, initially with little success, to convince investors that tapering was not tightening, so too officials will have to help investors appreciate the difference between thresholds and triggers.

The threshold has been approached in the UK. In effect, Carney said, “Yes, the unemployment is near the threshold we identified. We have reviewed the situation and have decided that it will still be some time before we think we will need to raise interest rates.” The lack of wage pressure suggests plenty of slack still in the labor market.

Yet one would be remiss if the analysis stops with these factors without considering the national level. Indeed, when looking what is happening in several countries, the international factors look relatively minor. Surely, one cannot ignore the domestic developments in Ukraine and Thailand for example.

Argentina, without much good will among investors, lost more confidence, not because the Fed tapering or China challenges, but because the President replaced her economic team in November and still has failed to rein in the large current account deficit or deal with the near 25% officially recognized inflation. Last week the central bank stopped throwing its reserves away (losing a third over the past year). Even with the peso’s decline, it is still well above the black market rate.

Look at Turkey. The political leadership is struggling as two Islamic factions clash. Turkey has a current account deficit of 7.5% and inflation around 7.5% as well. Seemingly due to political pressure, Turkey’s central bank refused to hike the overnight lending rate, which at 7.75%, is barely positive. Turkish reserves are only a little higher than Argentina’s.

This is not meant to be exhaustive, just suggestive of the role that national developments played last week in the meltdown seen in many emerging markets. We note that China’s shares were the best performer, with the Shanghai Composite up 2.5% and the smaller-cap Shenzhen Composite was up a little more than 5%. Equities also advanced in Taiwan, India, Thailand and Indonesia. According to data Bloomberg receives from the local stock exchanges, India, Indonesia, Philippines and especially Taiwan saw net foreign purchases last week.

Tags: current account,developed markets,Emerging Markets,Stock markets,Turkey