Before there could be “globally synchronized growth”, it had been plain old “global growth.” The former from 2017 appended the term “synchronized” to its latter 2014 forerunner in order to jazz it up. And it needed the additional rhetorical flourish due to the simple fact that in 2015 for all the stated promise of “global growth” it ended up meaning next to nothing in reality.

Oddly the same for 2017’s update heading into 2018 and 2019.

| If currency wars are the beggar-thy-neighbor approach to igniting one’s own economy at other’s expense, either “global growth” or “globally synchronized growth” had turned the concept on its ear. “Devaluation” would leave everyone pointing the finger at you for taking from everyone else in order to pick yourself up. Dreams of “global growth” started out with the finger pointing, only in a more positive if equally unrealistic way.

In other words, both “global growth” and “globally synchronized growth” had meant any specific national economy official would count on the “global economy” to get going and then spin off local benefits enough to pull whichever local official and their local economy out of trouble. It was a belated acknowledgement, of sorts, that local “stimulus” plans hadn’t actually panned out. Sure, we said our QE’s and fiscal spending would work here, but, apparently, they didn’t so maybe they worked elsewhere. As the rest of the world gets going again, success could be imported beginning with each export sector (the opposite of currency wars stealing more exports, “global growth” readily contributing them). |

|

Hardly anyone noticed this crafty rearrangement of some really basic theory, still infatuated with fancy “new” QE’s and such. Nowhere was that more evident than 2013 in Japan. Not only the Bank of Japan with its fanciest QE yet, QQE, before it had even begun already Japanese Economists were looking at this rather non-specific “global growth” thing as something like an insurance policy just in case QE10 (as QQE had been) performed about as well as each of the prior nine. From the BoJ:

So, if QQE doesn’t work in 2014 (spoiler: it didn’t, not at all) then “global growth” will bail the Japanese out. They always forecast happy endings. But what happens if, when, everyone is simply counting on the next guy? I’m expecting your economy to pick up which will benefit mine, and you’re expecting your neighbor’s economy to do the same, while our neighbor is, simultaneously, expecting my economy to accelerate enough to fix her mess. As I put it in 2014, we all end up doing little more than praying to the false god of global growth. Expecting the best from the “global economy” which can’t ever get out of the way of…something.

Since putting down those words six and a quarter years ago, two. Two more times “global growth” has failed because each time it was never a real thing. Slogans and half-truths, modest, increasingly minor reflations treated as the cosmic shift toward meaningful, sustained growth and recovery everyone keeps predicting out of nothing ever more than irrational hope. In the real world instead, the (euro)dollar standing in the way every time. Fast forward too many more wasted years, and while the latest slogan hasn’t yet coalesced into its most catchy, punchy final form, at root it is taking the same route as these other two. |

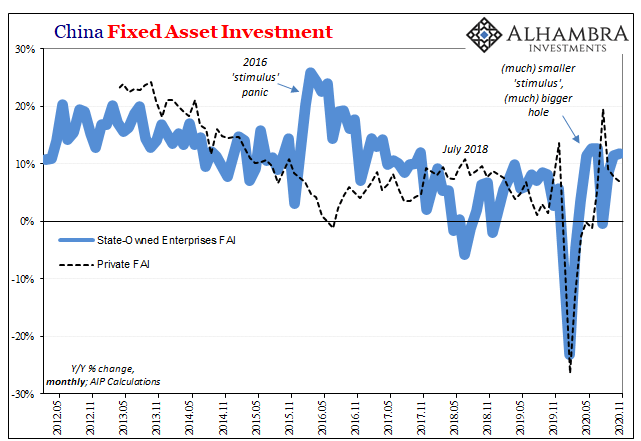

China Fixed Asset Investment, 2012-2020 |

| “Global growth.”

In the latest context an even greater emphasis on China’s role; the more implausible the worldwide recovery, the more the West expects from the Chinese to fix everything. If in 2014 I was the United States and Japan was Japan, our neighbor had been China. Rather than acceleration and picking up in any of them (throw in our other neighbor Europe for comprehensiveness), they all fell off together. The issue with “globally synchronized growth” was never the word “synchronized.” After the awfulness that has been 2020, next year, 2021, has been penciled in as a rebirth – according to many. Sure, the “V” didn’t fly up its second half as these had promised, but now there are vaccines and yet more QE/fiscal recklessness to fix the global damage we now all agree has already been done. If the Chinese come through with their part, pulling maybe a third of the “recovery”, according to the OECD, how could “COVID-free global growth” possibly go wrong? China, at this juncture, would like a word. This “global growth” stuff never passed muster in the Chinese sense; not in 2017, nor in 2014. It was all a Western-style fiction of good standing Economics (why it included the Japanese). As I also wrote in 2014, the Chinese never once saw this “global growth” stuff anywhere on their shores and the lack of it was itself steadily, profoundly weakening their economy. Same, obviously, in 2017 when Xi Jinping busily worked out how he was going to more ruthlessly rule a China without any plausible return to growth while clueless Western officials patted themselves on the back for the presumed cleverness inserting the expression “synchronized” into their little catchphrase. Now, 2020 presses toward its close and where is China in the “global growth” sweepstakes? Not anywhere near where it is supposed to be, where it obviously needs to be if “COVID-free global growth” is going to become what its predecessors never did. |

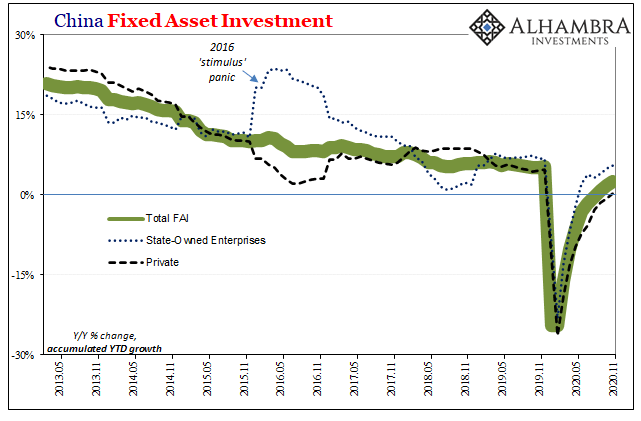

China Fixed Asset Investment, 2013-2020 |

| For one, it starts with “stimulus”; Xi’s gang isn’t buying the need, or at least seeing the potential benefits. Thus, there just hasn’t been much of any. State-owned FAI, a key measure of this stuff, is moving forward at half the rate of growth which had been considered normal around the time this “global growth” noise began after 2012.

The Chinese government just isn’t interested, not even in a 2016-kind of way which in many ways had supported the Western views of what could become “globally synchronized growth.” Like the related Inflation Hysteria #2 compared to Inflation Hysteria #1, “COVID-free global growth” has so much less going for it than what little “globally synchronized growth” had; which was itself already significantly lessened from plain “global growth.” The less actual growth, the more words apparently needed to distract from this. Industrial Production, according to newly released figures from China’s NBS, increased 7% year-over-year during November 2020. |

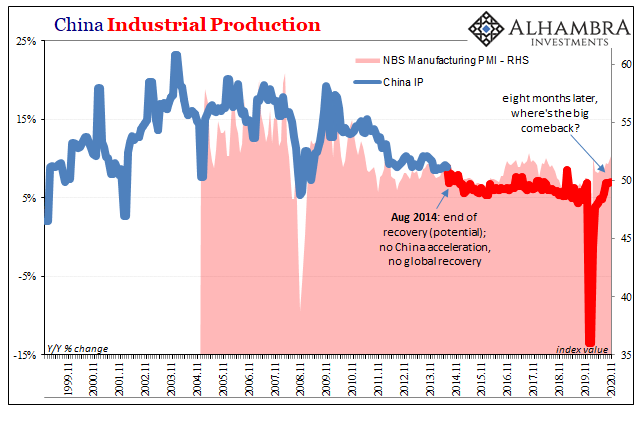

China Industrial Production, 1999-2020 |

| That’s the best rate of increase this year, and the best of the data – which isn’t all that much good.

As noted last month when IP was at 6.9%, this was a level which back in 2014 had triggered alarm bells among the less-irrationally hopeful. Honest analysis led observers then to question how “global growth” could possibly become a reality when the Chinese economy and its most outward-facing sectors were struggling so badly. But IP isn’t just 7% or 6.9% the last two months, it’s been right here for the last three. In other words, not accelerating, instead stuck at a low-level growth rate even after the enormous earlier decline. |

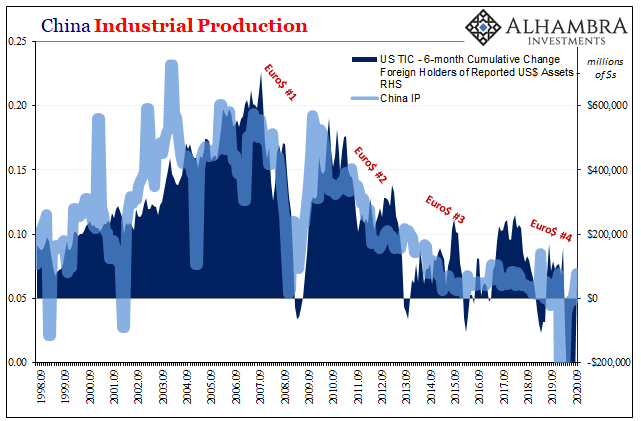

China Industrial Production, 1998-2020 |

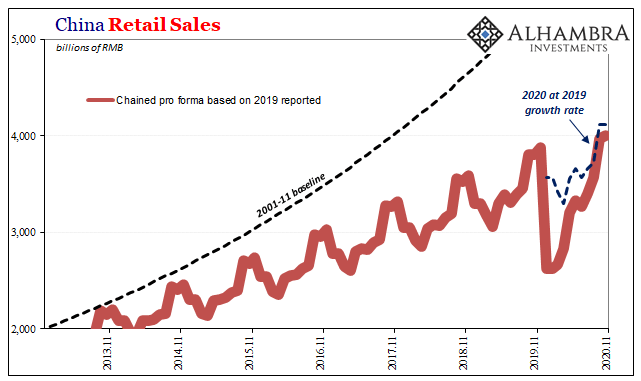

| This then leaves China’s internal transition as the final hope for this third stab at it. They called it “rebalancing” during the first one, and kept the name for “globally synchronized growth”, but now it is “dual circulation” for “COVID-free global growth” which begins in very large part from the assumption the Chinese economy expects little to nothing of any global growth. Like during those other two earlier periods, China today just isn’t seeing it (and is already planning for political life incorporating the grave dangers to the Communists without any).

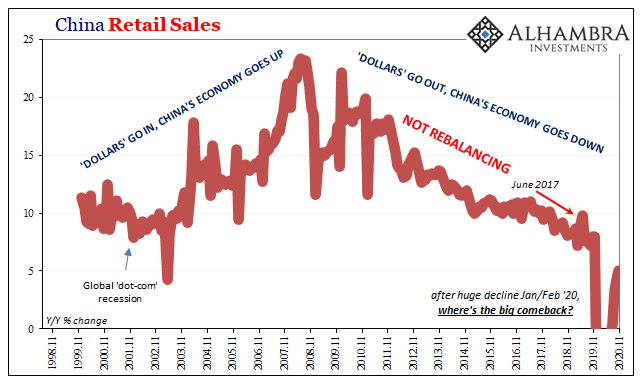

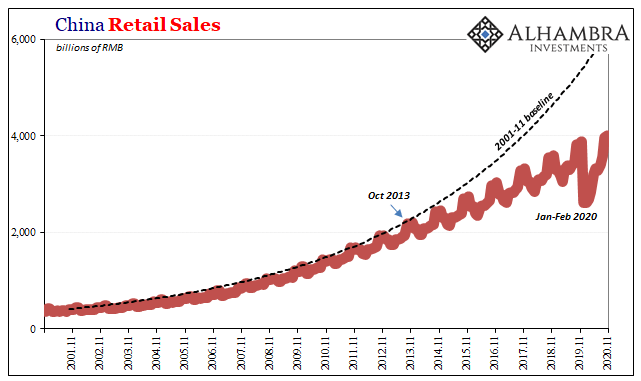

While IP stalls out, Retail Sales still haven’t come close to coming back. Growth improved only modestly in November, retail sales rising just 5% year-over-year. How bad is that? Other than the one aberrant month in 2003, not counting the estimates from the rest of this year, last month would’ve been the lowest on record. |

China Retail Sales, 1998-2020 |

| Global growth. Globally synchronized growth. COVID-free global growth. Each and every one exactly the same where they count. In all cases, they figure on China playing the key role. In the two of them completed so far, that irrational hope already proved fatal (which is why there’s now the three). So far of the third, what’s different? Other than the global economy being in materially worse shape, just like 2017 compared to 2014, it’s really the same. |

China Retail Sales, 2001-2020 |

China Retail Sales, 2013-2020 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: China,currencies,economy,fai,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,fixed asset investment,global growth,globally synchronized growth,industrial production,Markets,newsletter,Retail sales