This is yet another one of those crucial recent developments which should contribute much clarity about the economic situation, yet is exploited in other ways (political) adding only more to the general state of economic confusion. The shelves may be empty in a lot of places around the country, leaving anyone with the impression there just aren’t enough goods.

Shortage of goods, everyone’s thinking, by virtue of economics (small “e”) it will be another significant inflationary pressure. Maybe even the straw that breaks the post-70s camel’s back.

But is there actually a shortage of goods? Is that really what this supply shock is all about?

If there is one thing unambiguously in short supply, it’s actually physical structures and locations to warehouse goods.

Contrary to public perception, an enormous quantity of material is being produced and even shipped, the issue is that it can’t get as far as its destination because of bottlenecks/constraints in transit.

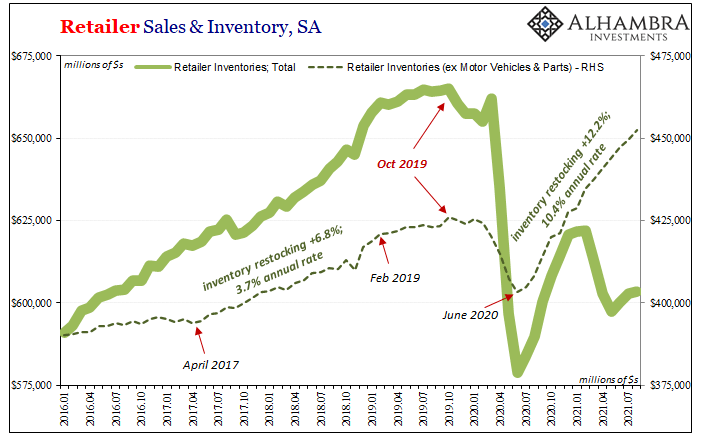

Outside of a few highly visible sectors, automobiles in particular, this unusual inventory cycle is being generated on the upside by how hard it is to transport things rather than having few things to transport. As we noted here, this has created a perverse chain of events whereby the ordering of goods is being conducted based on transportation worries rather than (honest) forecasts of end demand.

Suppose retailers (outside of automobiles) grow concerned about supply availability or shipping times. They might naturally react by boosting their current order flow if only to increase their chances some product makes it through the clogged shipping channels.

As that increased order flow unrelated to demand continues to move back through the supply chain, it probably would only make the transportation issues that much worse. It’s already a mess, and because it’s already a mess the entire supply chain tries to stuff more goods through it rather than less, rather than giving the system some time and space to work out enough kinks.

This would mean an overflow of goods but where many if not most of the goods lurk in the background, not anywhere visible at the end of the line. This is not a shortage. And if there is such a thing, then storage space would be the thing coming up for a huge price premium.

Last Friday, the Wall Street Journal reported:

One CFO at a major corporate real estate firm added, “Space in our markets is effectively sold out.” Part of the problem is post-pandemic behavior; locked down originally due to governmental indifference, consumers began buying even more goods online than they had been prior to 2020. This required retooling much (too much) of the way goods are handled from producer to wholesaler to retail delivery. |

|

| But as the economy seeks its way back to normal, Americans, in particular, are still buying online; as if years of a slower trend toward virtual shopping were condensed all at once into the calendar space of a few months.

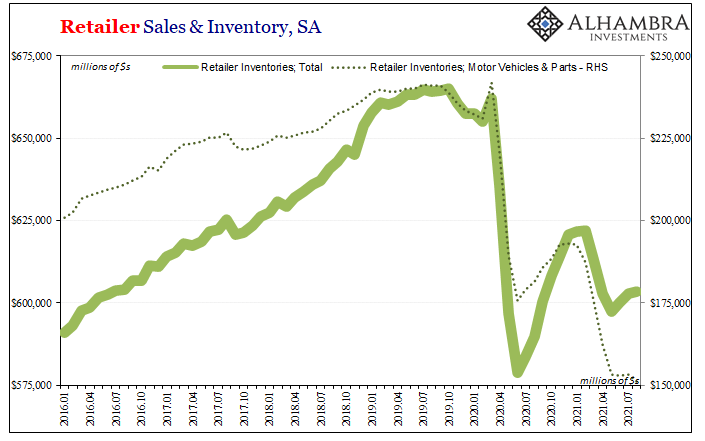

As we pointed out here, wholesalers have got product; a lot of inventory, if you exclude the effect of an auto sector plagued by an entirely different set of supply problems. In other words, for motor vehicles and parts, it is not the same thing at all as what’s going on everywhere else in the goods economy. |

|

| That’s not what the public is being led to believe, as social media flooded with images of empty shelves cultivate this misimpression how the whole economy must be in the same boat (pun intended) as the auto sector.

Stepping up the supply chain one rung, retailer inventories at first appear equally dismal (above); matching data with the perception of systemwide destocked shops. Inventory levels are at extreme lows, and inventory-to-sales ratios even more historically low still. However, if you deal with the situation in the automobile industry separately, as you should, excluding retail auto inventories what you find is goods flowing if not flooding on the retail level that along with wholesale inventories (ex motor vehicles) matches the shortage of warehouse space described in Friday’s WSJ. |

|

| Many companies have claimed they are absolutely ready for “too many goods”, believing both their newfound penchant for individual supply chains as well as logistical consulting to manage more than ever. This so long as demand doesn’t “unexpectedly” fall off, even a little, which then might trigger the downside of the inventory cycle.With this deluge of goods reaching US warehouses, wherever they might be in the country or within their own delivery process, it has to be a little unnerving how even mainstream commentary on the economy has itself shifted prominently. | |

| Earlier in the year, it was common enough (Warren Buffett!) to hear the term “red hot” thrown around regularly to the point of ubiquity.

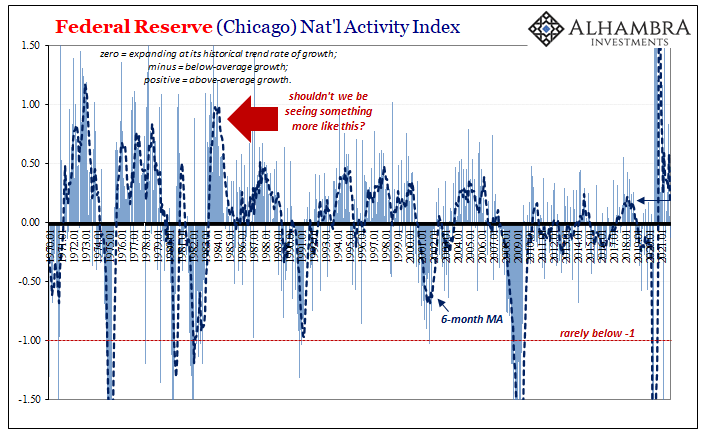

Nowadays, you are far more likely to encounter the tag “stagflation” with few references to overheating left outside of the FOMC members already having cornered themselves into tapering (and therefore having to “justify” the upcoming act by, yet again, like every other time, being overly positive interpreting otherwise not-so-great economic data). It was the “red hot” economy from early 2021 which had built up Corporate America’s inventory exuberance. |

|

| A stagflation economy, on the other hand, with warehouse space already at a huge premium, the “flation” part becomes increasingly settled into the opposite of the one most Americans are thinking, and it is in large part because of the real reason for so many empty shelves.

Excessive levels of inventory given just a downgrade in expected future demand (see: Chicago Fed National Activity Index above) becomes highly disinflationary at the drop of a dime, not inflationary. Depending upon just how much of a demand downgrade, given these other factors, an inventory cycle downswing could actually end up being outright deflationary. |

|

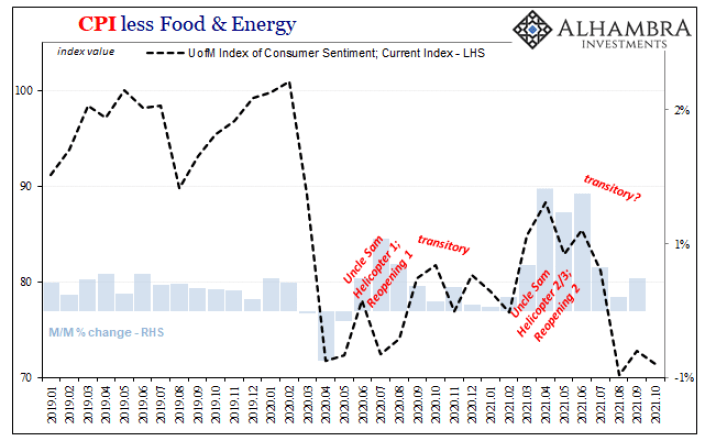

| It is understandable why Americans have been left to believe all these things add up to consumer price acceleration far into the future. Vast swaths of grocery and department store shelves which go on unstocked for a noticeably long period play along with the perception of a goods shortage, seeming to be consistent on the surface with the previous (earlier in 2021) burst of consumer price increases. |

While those price increases sure did happen, they were not inflation nor were they even a supply issue in the way it appears most people are being led to think of it. While there aren’t enough cars on dealer lots, the entire rest of the goods economy (apart from a few other sectors, like clothing) is on the verge of being overwhelmingly awash in all manner of non-auto stuff.

And this doesn’t even count what’s stuck afloat on logjammed ships already acting as warehouses-of-last-resort.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,currencies,Deflation,disinflation,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,inflation,Inventory,inventory cycle,Markets,newsletter