| One year ago, last October, the IMF published the update to its World Economic Outlook (WEO) for 2018. Like many, the organization began to talk more about trade wars and protectionism. It had become a topic of conversation more than concern. Couched as only downside risks, the IMF still didn’t think the fuss would amount to all that much.

Especially not with world’s economy roaring under globally synchronized growth. Even though there were warning signs already by then, the idea was that the upturn in 2017 had been a true recovery trend. That’s not something that gets upset easily and it wasn’t expected to.

|

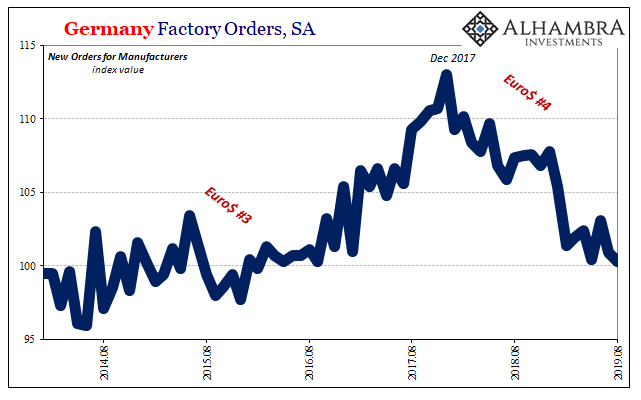

Germany Factory Orders, SA 2014-2019(see more posts on Germany Factory Orders, ) |

The IMF acknowledged that these downside risks shouldn’t be taken lightly, but overall it did not expect they would end up as more than historical trivia. More annoying than alarming. What were they? The IMF didn’t really know, citing pretty much everything:

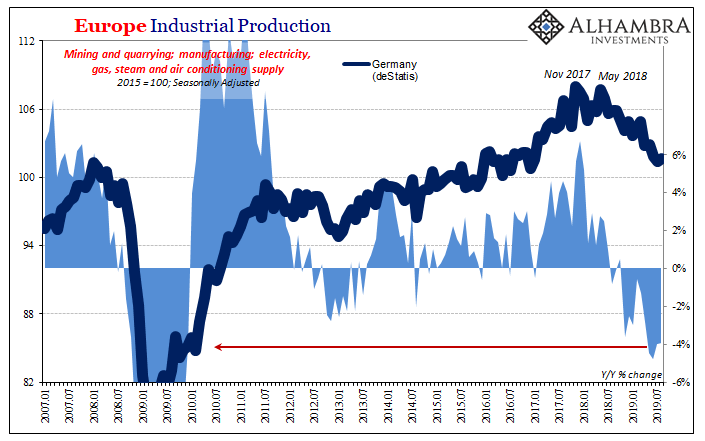

That first sentence is the key one. As we’ve noted ever since early 2018, it wasn’t trade wars, trade tensions, or tariffs which provoked a spreading and worsening economic backlash. It began right in January, following a December in 2017 full of warning signs in the one place where it always matters. The global dollar market, the eurodollar system. Germany is a perfect example of what I mean. The engine of Europe’s economy is defined – at the margins – in large part by global trade and global growth. Susceptible therefore to monetary swings, the sudden change in manufacturing and exports proposed already serious consequences from the shift in monetary conditions. The very moment the euro stopped rising is the same one Germany’s, and Europe’s, economy slammed into the wall. While the IMF and Mario Draghi continued talking about a robust boom with some minor downside risks, the whole thing had already started to reverse. That’s not a small forecasting miss; it is a large error of contemporary interpretation. |

Europe Industrial Production, 2007-2019(see more posts on Eurozone Industrial Production, ) |

| What we are really talking about here is the scientific process. I mean the real one, not the scientism that gets passed around nowadays, the very one practiced by Economists using exclusively econometrics. The latter is merely slapping some numbers into equations and no matter how inane and inappropriate the results they are taken as equivalent to objective truth. Math does not mean science.

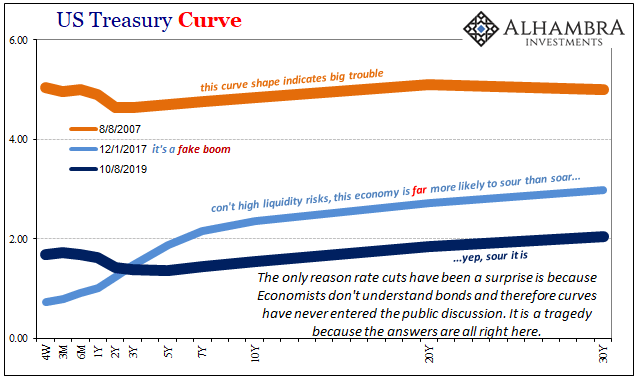

Science is instead a process. You make predictions and examine evidence. The validity of any assumptions is predicated on observations, not whether the equations balance. If the models say that trade wars are going to be a minor nuisance and nothing more than a slight downside risk, if it turns out otherwise (observation) it invalidates the theory. Based on the global bond market view of things, how the curves had behaved and one important curve (eurodollar futures) that had inverted, there was another set of predictions which were much easier to make. Only, they didn’t comport with the idea behind globally synchronized growth even if that’s where they started. Three days before the IMF released its October 2018 WEO, I voiced my own simple projections.

No real insight on my part, just keeping to simple observations; repeated observations, the stuff of science. The key has been only to realize what’s actually going on in the global monetary system regardless of what global central bankers say. From that you further grasp how powerful and powerfully destructive those conditions can become when the system swings in the wrong direction (again). |

US Treasury Curve, 2017-2019(see more posts on U.S. Treasury, ) |

It wasn’t necessarily a foregone conclusion, but there really wasn’t much chance for another outcome. As I asked last year, what comes next? The IMF at its annual meeting yesterday finally admits to the obvious answer (thanks M. Simmons):

And why now a globally synchronized downturn? According to the IMF it is because…trade wars. That’s what’s so important about Germany. Not just that it’s a central pivot in the European economy and the global system overall, but what does Germany in January 2018 have to do with a few billion in new US duties on Chinese imports? Nothing. The global system had already turned before anyone was speaking the language of protectionism. The eurodollar squeeze was in play and had created noticeable global disruptions by the time anyone at the IMF or anywhere else finally noticed them. Which is a shame because in that October 2018 WEO the organization actually mentioned it – “tighter financial conditions” – even if incorrectly attributing the negative factor to “rate hikes” rather than the growing global dollar shortage. A whole chain of bad theory and unmade observations, even about things observed. |

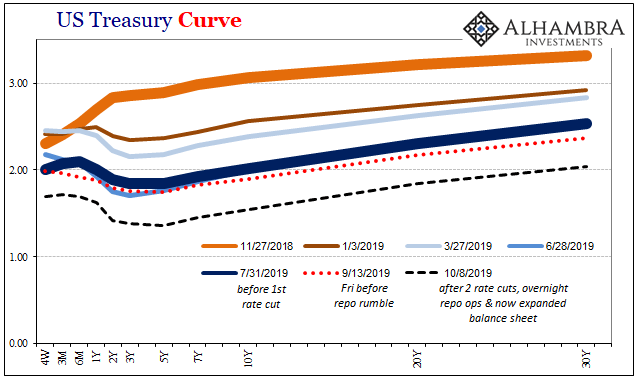

US Treasury Curve, 2018-2019(see more posts on U.S. Treasury, ) |

The eurodollar (liquidity perceptions) had told the bond market to expect a downturn (and rate cuts) or worse in 2019 while trade wars told Economists globally synchronized growth would continue uninterrupted (with inflation and rate hikes). And that was before September 2019’s repo rumble.

Now that the world is slowly waking up to this other, dangerous reality, who is everyone going to listen to about how we got here? The practitioners of scientism, of course. Just as Euro$ #3 would only ever have led to Euro$ #4. And that’s why Euro$ #4, no matter how it turns out, will be followed by nothing more than Reflation #4 which will of course lead to Euro$ #5. Like subprime mortgages, PIIGS bonds, and the oil glut, trade wars not required.

The science of it, though, isn’t the numbers.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,currencies,economy,EuroDollar,Eurozone Industrial Production,factory orders,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Germany,Germany Factory Orders,global dollar shortage,globally synchronized downturn,globally synchronized growth,IMF,industrial production,Markets,newsletter,U.S. Treasury