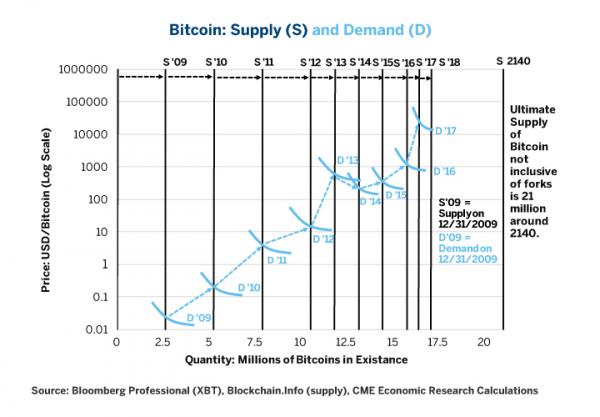

Our earlier articles on bitcoin discuss the crypto asset as a currency and a commodity. Both papers focused on the consequences of bitcoin’s defining feature: the asymptotic supply limit of 21 million coins. This gives it an unusual juxtaposition of demand uncertainty and supply certainty (as well as inelasticity). As a currency, it gives rise to a tension between its use as a store of value and as medium of exchange. Like commodities, it has a mining cost of production that both influences and is influenced by price. Finally, we explored bitcoin’s demand dynamics and the problems posed by rising transaction costs and their potential to trigger price crashes. This paper explores bitcoin as an equity, and more specifically as the first equity ever launched by a non-hierarchical “teal” organization, a self-driving entity with an independent force and purpose, its role in promoting blockchain and the potential consequences of bitcoin and blockchain for the economy.

While bitcoin is most commonly described as a currency, one can argue that it also has equity-like characteristics. These arguments can be both narrow and legal in nature as well as deeper and more philosophical. From a legal perspective, many governments are moving to regulate initial coin offerings (ICOs) of cryptocurrencies as they do initial public offerings (IPOs) of equity and other securities. Bitcoin’s ICO occurred in 2009 and at the time was largely overlooked by regulators. No longer. With over 1,000 additional cryptocurrencies being launched during the past two years, regulators worldwide are playing catch up, considering their response to this occurrence.

On an economic and financial level, bitcoin also exhibits equity-like characteristics. The rewards that miners and those validating transactions on the bitcoin blockchain receive are analogous to stock grants made to employees by corporations. The stock of a company can be seen as an internal currency used to compensate and motivate employees, aligning their interests with those of the organization. To that end, the number of bitcoins in existence is comparable to the “float” of a corporation – the number of shares issued to the public.

When bitcoin forks into a new currency, such as bitcoin cash, the move is comparable to a corporate action such as a spin out. In a spin out, a corporation can give each of its shareholders new shares in a division of the firm that is being released to the public as separate and independent entity. In September 1996, for example, shareholders of the communications giant AT&T found themselves owning two stocks: that of AT&T services business, and that of Lucent Technologies, a phone equipment maker, of which AT&T (wisely) divested itself. Likewise, when bitcoin most recently forked, the owner of each bitcoin received one bitcoin cash, a new and separate cryptocurrency.

While bitcoin is not by any means a traditional corporate entity with earning statements and a board of directors, it could be seen as an equity in its own ecosystem whose value derives from the size and health of that community. What is clear is that if bitcoin is equity, it represents a radically different corporate form than has ever created before.

| It appears to be one of the first examples of what sociologist and organizational development specialist Frederic Laloux describes as a “teal organization”: an organization with fluid hierarchy that is adaptive and rules-based where authority is decentralized and distributed among members. That such an organizational form would arise around a distributed ledger is perhaps not surprising but it does, nevertheless, represent a radical new experiment in human organization. In his book, Reinventing Organizations, Laloux describes five organizational types: red, amber, orange, green and teal (Figure 1). Red organizations are primitive tribal groups led by a single person. Street gangs and the mafia are modern examples. By their nature they are unstable: when the leader dies or becomes impaired, there is a fight for control and the organization can disappear or split if a new leader does not emerge. See Francis Ford Coppola’s “The Godfather” series for details. |

Organizational Theorist Frederic Laloux’s Five Kinds of Human Organizations |

Amber organizations, the world’s first and oldest bureaucratic form, represent a radical innovation: an immutable organizational command-and-control hierarchy that survives and outlasts any member. Organized religion, government bureaucracies and militaries are examples of amber organizations.

Most corporations are either orange or green organizations. Compared to amber organizations, orange ones feature additional agility. While they maintain strict hierarchies, they form more ad hoc project groups, have greater differentiation in expertise, and change the size, scope and form of their hierarchies in conjunction with needs. They can also merge and split apart peaceably. Green organizations take this approach further, often decentralizing decision-making to frontline employees. They tend to be somewhat flatter and management is meant to enable the success of frontline employees in a partial reversal of (or at least a more two-way version of) the usual top-down reporting lines.

Until the creation of bitcoin, teal organizations were mostly theoretical, although Wikipedia could be considered an example. What Wikipedia and bitcoin have in common is that both are essentially non-hierarchical organizations in which users make voluntary contributions to the development of the entity. For Wikipedia, this comes in the form of writing and editing articles on millions of subjects in dozens of languages in accordance with the rules of the organization. For bitcoin, the voluntary contributions come in the form of mining bitcoin and validating transactions. What differentiates bitcoin from Wikipedia is that the latter is a not-for-profit organization that requires periodic, voluntary monetary contributions from supporters. Bitcoin, by contrast, rewards contributors economically in a manner somewhat analogous to orange or green corporations but with much stricter, and less political, rules for who gets paid what and why. Little wonder that bitcoin and its crypto peers are described as “the internet of money.”

Bitcoin’s limit on supply to 21 million coins is also open to a useful equity analogy. This limit on the number of coins is one of the reasons why we think that bitcoin is useless as a medium of exchange and is being treated, rightly or wrongly, as a highly volatile store of value, sort of like gold on steroids. Bitcoin could become a more useful medium of exchange if it increased the cap on the total number of coins. So, why doesn’t it? Corporations have the option of issuing more shares. For example, in the early days of the Great Recession, many banks issued more shares to recapitalize themselves. The problem with issuing more shares is that it dilutes the value of the existing equity holders and usually lowers the price of a stock. As such, aside from compensating themselves and some of the employees with share options and share grants, corporate managements avoid issuing more shares like the plague. And normally, equity holders want such share grants to be limited so as not to be excessively dilutive.

We don’t know if the bitcoin user community will one day allow for the creation of more than 21 million bitcoins. If they do, it would improve the value of bitcoin as a medium of exchange but it would likely come at the expense of bitcoin holders’ value. As such, we are not sure why existing bitcoin holders would agree to such a change. Nor is it clear why the miners and transaction validators would agree to such a change, which would likely lower their profit margins.

Lots of Pots, Lots of Kettles

While there is much truth to saying that bitcoin has no inherent worth, there are lots of glass houses in this financial neighborhood, so one should be careful about throwing stones. Cryptocurrencies, including bitcoin, are unique. That said, one can understand them better by drawing analogies to a variety of more familiar asset classes, including fiat currencies, commodities and equities. However unique, bitcoin carries characteristics of all of these assets to which we are more accustomed.

Bottom line:

- In addition to currency and commodity-like characteristics, bitcoin also resembles equity.

- Bitcoin can create spin offs (hard forks).

- Bitcoin miners and transaction validators are compensated with bitcoin in a manner analogous to companies granting stock to employees.

- Like Wikipedia, cryptocurrencies represent non-hierarchical “teal” organizations in which people make voluntary contributions.

- Bitcoin is a bit like an equity on an ecosystem that surrounds the crypto asset rather than a traditional hierarchical corporate entity.

- If there is indeed a crypto bubble, it may be financing and incentivizing the creation of a new generation of powerful computers which could have widespread and unpredictable future applications.

- Investors in cryptocurrencies may or may not benefit from popularizing the blockchain and distributed ledgers.

- At the moment, bitcoin is too small to pose any threat to the stability and continued growth of the global economy but this could change if the currency rises to a much higher value and then collapses.

Tags: Alan Greenspan,Alternative currencies,Bitcoin,Blockchains,Business,central banks,Crude,Crude Oil,Cryptocurrencies,Currency,Digital currency,Economics of bitcoin,federal government,Finance,Ford,Futures market,Global Economy,housing bubble,Legality of bitcoin by country or territory,Meltdown,Monetary Policy,money,NASDAQ,Nasdaq 100,Natural Gas,New Zealand,newslettersent,recession,Swiss Franc,Volatility,Yen

1 comments

Panda

2018-03-14 at 00:57 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

The laughing sounds you’ll hear will come from those who short the crypto bubble before it bursts.

The hilariously former-rich speculators will lose their shirts, pants, houses, cars, boats, businesses, families and lives….taking down the global economy with them.

Oh, but nobody saw this coming…..