Incrementum Advisory Board Meeting Q4 2017 – Special Guest Ben Hunt, Author and Editor of Epsilon TheoryThe quarterly meeting of the Incrementum Fund’s Advisory Board took place on October 10 and we had the great pleasure to be joined by special guest Ben Hunt this time, who is probably known to many of our readers as the main author and editor of Epsilon Theory. He is also chief risk officer at investment management firm Salient Partners. As always, a transcript of the discussion is available for download below. As usual, we will add a few words here to expand a little on the discussion. A wide range of issues relevant to the markets was debated at the conference call, but we want to focus on just one particular point here that we only briefly mentioned in the discussion. In fact, as you will see we are about to go off on quite a tangent (note: Part II will be posted shortly as well). Among the things Ben Hunt specializes in are the narratives accompanying economic and financial trends, and not to forget, economic and monetary policy, which inform the “Common Knowledge Game” (in his introductory remarks, Ronald Stoeferle provides this brief definition: “It’s not what the crowd believes that’s important; it’s what the crowd believes that the crowd believes”). This reminded us of something George Soros first mentioned in a speech he delivered in the early 1990s:

This is undoubtedly a great insight and great advice for traders and investors. Long-time readers may recall that we have occasionally mentioned in these pages that Ludwig von Mises described successful speculators as akin to “historians of the future”. Soros appears to have a very similar view of speculators.* We believe that being au fait with sound economic theory to some extent can be helpful for people investing in financial markets, but a good grasp of economic history seems even more important. The process speculators employ to arrive at their decisions has certainly more in common with what Mises called the understanding of the historian than with economic theorizing. Knowledge of theory can improve and refine said understanding though, and help constrain forecasts. Soros coined the term “reflexivity”, which describes something very similar – as he put it, it sets up a feedback loop between market valuations and the fundamentals that are being valued. This is something we can nowadays e.g. observe among junk bond buyers and their odd beliefs about future default rates. The reflexivity consists of the fact that these default rates depend to a substantial extent on their own willingness to refinance junk-rated companies, many of which would perish if they stopped doing so. In other words, the state of their own confidence contributes decisively to “fundamentals” that are highly important in determining the solvency of the borrowers they continually evaluate. It doesn’t get more reflexive – and as we mentioned, when buyers of euro area junk bonds are paying yields as low as those on US treasuries, it is pretty certain that this confidence is somewhat misguided. |

Ben Hunt, author of Epsilon Theory and chief risk officer of Salient Partners |

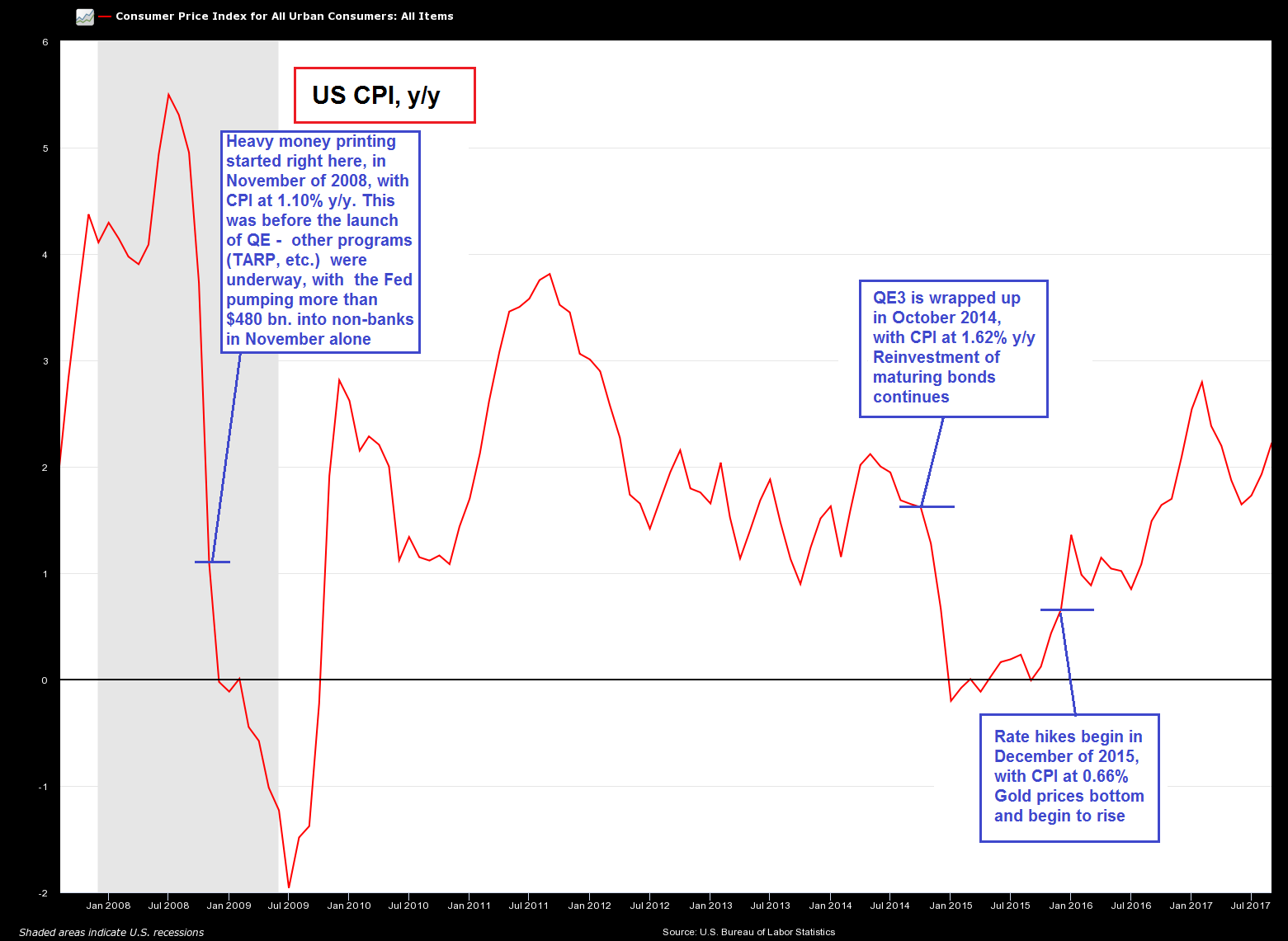

The Inflation NarrativeTo come back to Ben Hunt’s observations about narratives: once a powerful market trend has been underway for some time, countless rationalizations are usually offered to justify prevailing valuations. As a rule these aim to convey the idea that one should expect the trend to continue, regardless of how outrageously distorted or extended it seems to be in terms of traditional metrics. Policymakers feel compelled to provide narratives rationalizing their decisions as well, which are subsequently incessantly echoed in the media (this is how they become “common knowledge”). Ben Hunt mentioned a specific narrative that has accompanied quantitative easing for almost a decade now (even longer, if we take Japan into account). At first glance it appeared reasonable enough: central bankers argued that QE would help increase “inflation”. This is of course unequivocally true in terms of monetary inflation, but they referred to consumer price inflation. Alas, both CPI and inflation expectations obviously failed to respond appreciably to their ministrations. Ben posits that this narrative may be set to falter in a rather unexpected manner, by continuing to defy widespread expectations. US CPI y/y and three major changes in Fed policy – the beginning and end of active money printing operations and the beginning of the rate hike cycle. QE has done all sorts of things, but CPI has essentially gone nowhere, particularly while QE was still underway (QE 3 ended in October 2014) – click to enlarge.

In short, the idea is that the end of QE, or rather its upcoming unwinding (“quantitative tightening”), may be accompanied by an unexpected increase in consumer price inflation. One cannot help but be sympathetic to this idea simply based on how contrarian it is. Meaningful consumer price inflation is pretty much the last thing anyone expects. We actually briefly discussed this aspect in these pages back in March in “Price Inflation – the Ultimate Contrarian Bet”. At the moment we are still inclined to believe that a sizable future decline in asset prices is likely to create another deflation scare and will at least initially exert further downward pressure on inflation expectations. Nevertheless, we concede that Austrian business cycle theory (ABCT) would actually allow for the outcome suggested by Ben. |

US Consumer Price Index, jan 2008 - Jul 2017(see more posts on U.S. Consumer Price Index, ) US CPI y/y and three major changes in Fed policy – the beginning and end of active money printing operations and the beginning of the rate hike cycle. - Click to enlarge QE has done all sorts of things, but CPI has essentially gone nowhere, particularly while QE was still underway (QE 3 ended in October 2014) |

Operation ImpoverishmentIt should be noted that there is no single “canonical” exposition of ABCT (as Roger Garrison has put it**); rather, the individual accounts should be seen as complementary. Of course all ABCT expositions are based on the same ideas in terms of monetary and capital theory: credit expansion artificially pushes market interest rates below levels that would be in line with consumer time preferences; relative prices in the economy change as interest rates are suppressed, which falsifies economic calculation; this in turn triggers malinvestment, leading to an inter-temporal distortion of the capital structure that eventually proves unsustainable. Of course, every boom induced by credit expansion has beneficiaries; but even these beneficiaries can end up “holding the bag”, depending on how precisely events play out and their sense of timing. What is clear though is that for society at large, it means mainly one thing: impoverishment. This is to say, impoverishment relative to the satisfaction that could have been attained without the credit boom. Usually we still tend to end up more prosperous after a boom collapses than we were before it began (in most cases, that is). But we could do a lot better than that and at the same time avoid heaps of stress and injustice. As an aside to this: when a central planning agency engages in direct monetary pumping, one can probably speak of deliberate impoverishment. Perhaps innocuous-sounding slightly Orwellian euphemisms such as quantitative easing or asset purchase program should be changed accordingly. One can simply refer to such activities as money printing, but renaming QE to DI might have more punch. The danger of future economic history turning into a “never-ending series of episodes based on falsehoods and lies” would definitely recede. Just think about the truthiness coefficient of future headlines, it would be downright awesome: “The Fed just announced Deliberate Impoverishment IV”. Anyway, the reason why no simple, singular account of ABCT is available is the sheer complexity of the events involved. Variations in the sequence of these events and their specific shape depend not only on economic laws, but also on concrete historical and institutional settings, and different authors have placed more emphasis on factors that seemed particularly relevant to their times and personal experience. |

|

Business Cycles and Consumer Prices – Some BasicsPast booms were sometimes accompanied by very low consumer price inflation, usually when economic productivity rose significantly as new technologies became economically viable and enabled entrepreneurs to take large strides in improving production methods (e.g. in the 1920s and the 1990s), while at the same time creating entire new groups of products and services and the industries providing them. This type of boom was characterized by both malinvestment in the higher stages and widespread over-consumption, with the latter eventually giving way to forced saving and the former to liquidation once the boom began to turn to bust. The pernicious effects of credit expansion tended to be masked during these boom periods; the only immediately obvious warning signs consisted of unusually large increases in asset prices and rapid debt accumulation – both of which are widely regarded as harmless as long as the boom persists. Note that in such cases, a lot of genuine wealth creation will occur in parallel with the capital consumption fostered by boom conditions. This is both a blessing and a curse – the curse consists of the leeway and and incentives this backdrop provides for engaging in particularly egregious expansions of circulation credit (as we have pointed out in the past, pursuing “price stabilization” policies becomes especially dangerous under such circumstances). On the opposite end of the spectrum we find crack-up booms such as the tragic hyper-inflation calamity of the Weimar Republic, during which prices obviously rose sharply. The cycle was strongly compressed in time, and some of the typical effects on the capital structure were particularly severe.

|

|

| Specifically, an extremely pronounced imbalance of investment in higher vs. lower stages could be observd in this instance, in concert with a crushing and lengthy period of forced saving. While the owners of coal mines and steel mills still marveled at how great their businesses seemed to be doing, no-one could accuse the general citizenry of indulging in over-consumption.

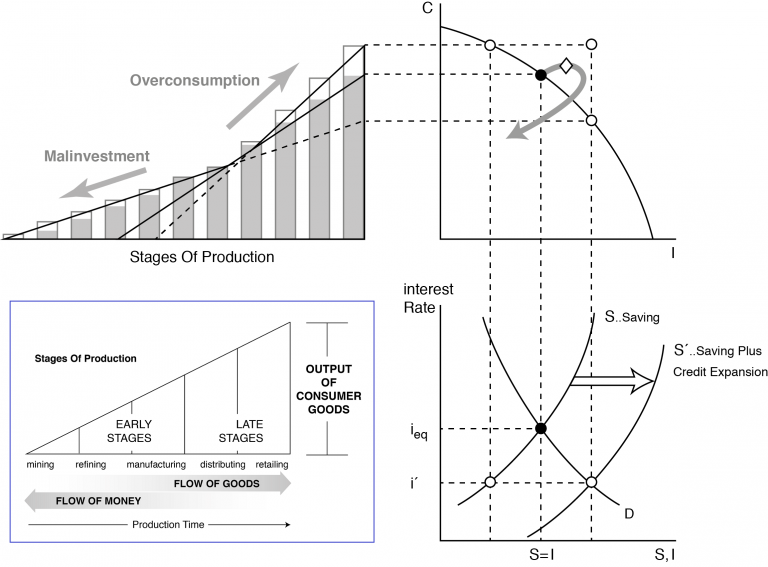

Wage earners had to involuntarily curtail consumption fairly early in the boom already, as their wages failed to keep up with rising prices. Business activities close to the consumer accordingly faltered, while investment in mines, factories, large piles of raw materials, inventories of highly non-specific capital goods, etc., reached truly bizarre proportions. Banks were forced to shift their business focus to stock market and currency speculation, as lending became an utterly suicidal proposition (the central bank was lending directly to businesses to keep the show on the road).*** Generally one could probably say that a crack-up boom is a boom with a strong depression undertone, a bit like the very last party just before the end of the world. A more conventional boom seems more relevant to present times though, so here is a visualization of type one – a very simple, but quite nicely done illustration of the basic elements of a business cycle that is characterized by a combination of malinvestment and over-consumption (the chart is adapted from Roger Garrison’s Time and Money****) |

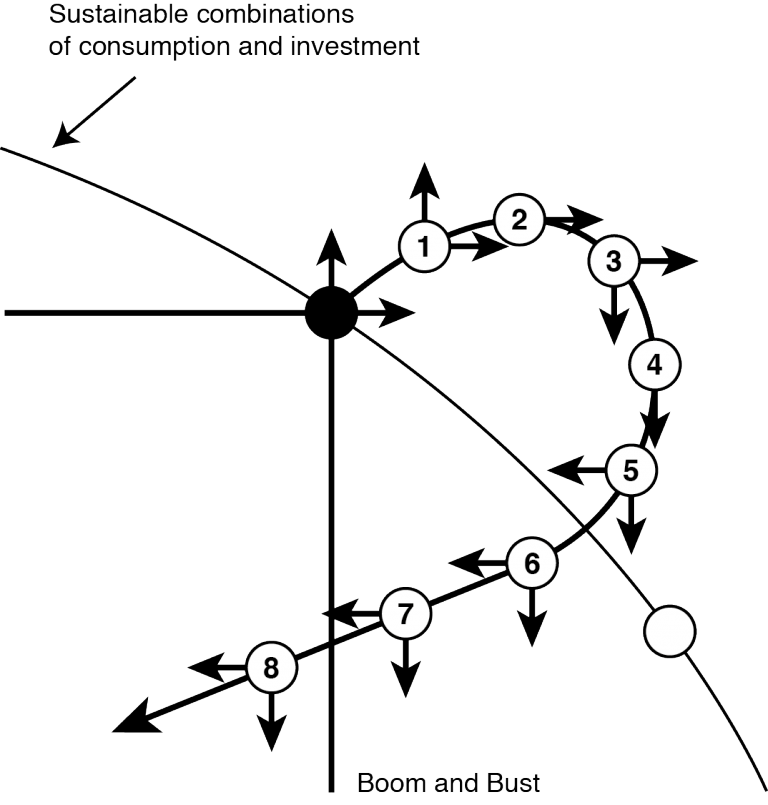

Note: we have inserted a more descriptive image of the “Hayekian triangle” inside the blue rectangle in the lower left quadrant as a conceptual aid – it is otherwise not part of this chart, - Click to enlarge It is mainly meant to help readers who are not familiar with the concept of the production structure. The rest of the chart depicts a credit boom characterized by both malinvestment in the higher stages of the capital structure and over-consumption, similar to what occurred in the booms of the 1920s and 1990s. The more temporally distant stages are from consumption, the greater their interest sensitivity. Artificial lowering of interest rates through credit expansion fosters capital malinvestment by drawing more and more resources toward higher order stages of production as their profitability appears to increase. As the illusory accounting profits of booming sectors begin to be distributed, over-consumption begins to pull resources toward lower order stages of the capital structure as well, and the Hayekian triangle becomes distorted in both directions (the middle stages so to speak bear the brunt of the abuse). In the upper right hand quadrant we see the curve representing the production possibilities frontier (PPF), on which all sustainable combinations of consumption and investment are located. Which combinations can in fact be sustained is determined by the volume of loanable funds provided by voluntary savings S and the associated natural interest rate i-eq in the lower right quadrant of the diagram. Loanable funds consisting of “savings augmented by credit expansion” S’ are represented by the right-shifted curve in the lower quadrant. The demand for loanable funds intersects both curves at the interest rate levels designated i-eq and i’. The curved arrow in the upper right quadrant crossing the PPF shows the path the economy eventually takes from boom to bust if savings are augmented to S’ by credit expansion and the associated interest rate declines to i’. The hollow diamond outside the PPF represents the height of the boom. The various self-reinforcing phenomena during the bust entail temporary movements of both C and I to points below the PPF (a.k.a. the “secondary depression”) |

| In the crack-up boom case, the bust is usually more benignly referred to as a “stabilization crisis” (since it is clear to everybody that things can only get better once the boom ends). In this type of crisis the previously suffering sectors close to the consumer tend to recover with a fairly small time lag, usually well before the severe bust in the higher stages is over, but not to an extent sufficient to prevent common bust-related symptoms (such as rising unemployment, waves of insolvencies and zombified banks). While detailed and reliable historical data on such events are sparse (as they are often chaotic, particularly in the final phase), those that do exist are very much in line with the tenets of business cycle theory. |

A close-up of the temporary movement of the economy beyond the PPF, and the subsequent movement toward a point below the PPF. The numbered circles and arrows denote the following sequence of events: at point 1, both malinvestment in the higher stages and over-consumption occur. At point 2, over-consumption reaches its maximum, at point 3 forced saving relative to the maximum level of consumption begins. At point 4, the maximum demand for resources to be allocated to higher order stages of the production structure occurs, at point 5 the liquidation of malinvested capital begins. Points 6 to 8 denote the bust – a movement below the PPF, i.e., the “secondary depression”. This “feel-bad” phase is unavoidable (even though its extent and duration is by no means predetermined), as it takes time and effort to bring the capital structure back in line with a sustainable consumption-investment balance that properly reflects actual consumer wishes. |

A Third Possibility

In the two types of boom-bust sequences discussed above, the bust periods traditionally tend to be accompanied by downward pressure on price inflation and inflation expectations. This happens even nowadays, although it is well-known that central banks will almost immediately implement heavy monetary pumping measures when the economy seems to be weakening. This response has become de rigeur in the fiat money era, especially over the past three decades, as the price inflation bugaboo has taken a remarkably persistent leave of absence.

They are not the only types though: as was demonstrated in the 1970s, another outcome is possible after an extended boom. In the 1970s the economy suffered a series of “stagflation” type busts – and nota bene, when the decade began , the consensus of mainstream economists was that this was impossible.

Contingent circumstances once again played an important role in the monetary and economic trends of the decade, but it is actually fairly easy to provide a logical explanation for this “inflationary recession” phenomenon – if anything, it is mildly surprising that it hasn’t happened more frequently.

– to be continued in Part II

Footnotes & References:

* Soros expanded on his original speech in 2010, rightly criticizing EMH (efficient market hypothesis), as well as the excessive reliance of modern-day economists on equilibrium models (equilibrium can never be reached in the real world, which they sometimes seem to forget. Even if it were possible, it would definitely not be a desirable state of affairs worth striving for). He cited a number of interesting ideas on bubbles, such as the proposition that a “super-bubble” has formed out of a succession of many smaller ones.

To be sure, we have a number of criticisms as well. Soros completely lost us when he asserted that the “false premise” he had spotted was “market fundamentalism” – and then proceeded to enumerate one example of government intervention after another to buttress this claim. He literally described these massive interventions as examples of “leaving the markets alone”, i.e., he seemed to think they constituted a policy of laissez-faire, which is downright absurd, to put it mildly (many intelligent people on the political left evince similar cognitive dissonance. As an example, Noam Chomsky is able to deliver a trenchant analysis of the war racket and the insidious propaganda that supports it and he clearly knows what he is talking about. As soon as he veers toward presenting his proposals for resolving the problems he has identified, he comes across as oscillating between incredibly naïve and complete insane – particularly in light of his analysis.). Also, while Soros’ observations on market psychology were certainly astute, he refrained from bringing his ideas into context with the monetary system. Since there is no such thing as a non-monetary business cycle (and bubbles in titles to capital and/or other assets are symptoms of boom conditions), it seems quite an oversight to not even mention money and credit in passing when discussing bubbles. [Note: the speech and variations thereof can be easily found with a Google search]

** see: Roger W. Garrison, The Austrian Theory of the Business Cycle in the Light of Modern Macroeconomics, Review of Austrian Economics, vol. 3

***Economic progress was replaced by the mindless duplication of already existing investments (at board meetings, conversations about investment planning conceivably sounded as follows: CFO: “…and we have about 75 million wheelbarrows full of cash, not sure how much that exactly is, but I think we should invest it as quickly as possible…any ideas?”. CEO: “Build another car factory”. CFO: “But we already have 179 car factories, and no-one can afford to buy our cars…” CEO: “Tell you what, build another two, then we’ll have 181. And while you’re at it, buy 30,000 tons of steel and put it somewhere on our premises…maybe next to that mountain of coal” – etc.). For an extensive and fascinating study of the crack-up boom see Italian economist Costantino Bresciani-Turroni, The Economics of Inflation: A Study of Currency Depreciation in Post-War Germany [free PDF download here]

****see: Roger W. Garrison, Time and Money: The Macroeconomics of Capital Structure, Routledge Foundations of the Market Economy, 2000/2001 [link to a very sympathetic critique by Randall Holcombe, PDF]. The book compares Austrian capital theory with Keynesian labor-based macroeconomics; we would not necessarily recommend it to beginners [here is a link to a PDF version].

Addendum & Download Link

We wanted to briefly add that apart from special guest Ben Hunt, regular advisory board member Jim Rickards joined us again this quarter as well, and contributed quite a few interesting observations, particularly about the Fed and recent geopolitical tensions.

– Here is the download link for the transcript of the Incrementum Advisory Board Conference (PDF)

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: central-banks,newslettersent,On Economy,U.S. Consumer Price Index