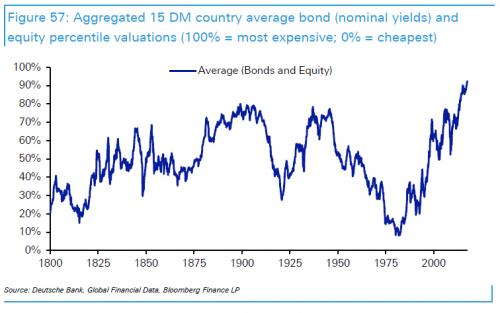

| In an extensive, must-read report published on Monday by Deutsche Bank’s Jim Reid, the credit strategist unveiled an extensive analysis of the “Next Financial Crisis”, and specifically what may cause it, when it may happen, and how the world could respond assuming it still has means to counteract the next economic and financial crash.In our first take on the report yesterday, we showed one key aspect of the “crash” calculus: between bonds and stocks, global asset prices are the most elevated they have ever been.

With that baseline in mind, what happens next should be obvious: unless one assumes that the laws of economics and finance are irreparably broken, a deep recession and a market crash are inevitable, especially after the third biggest and second longest central bank-sponsored bull market in history. But what will cause it, and when will it happen? Needless to say, these are the questions that everyone in capital markets today wants answered. And while nobody can claim to know the right answer, here are some excerpts from what DB’s Jim Reid, one of the best strategists on Wall Street, thinks will take place. Below we present the key excerpts from his must read report; * * * |

Average Bonds and Equity, 1800 - 2014 |

| We think that the post Bretton Woods (1971-) global financial system remains vulnerable to financial crises. A simple internet search of financial crises through history (Figure 1, LHS chart) confirms that the frequency has increased over this period. Examples include the UK secondary banking crisis (1975), the two Oil shocks (1970s), numerous EM defaults (mid-1980s), US Savings and Loans mass failures (late 80s/early 90s), various Nordic financial crises (late 80s), Japanese stock bubble bursting (1990-), various ERM shocks/devaluations (1992), the Mexican Tequila crisis (1994), the Asian crisis (1997), the Russian & LTCM crisis (1998), the Dot.com crash (2000), the various accounting scandals (02/03), the GFC (08/09) and the Euro Sovereign crisis (10-12).

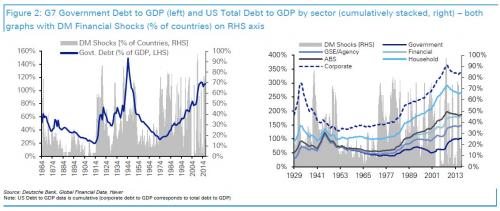

A more quantitative search backs this up (Figure 1, RH chart). We show the number of DM countries (%) in our sample back to 1800 experiencing one of the following on a YoY basis; -15% Equities, -10% FX, -10% Bond move, a sovereign default, or +10% inflation. This is our crisis/shock indicator. 0% equals no country with one of these conditions met, 100% equals all in our sample with one being met. It would therefore take a huge leap of faith to say that crises won’t continue to be a regular feature of the current financial system that has been in place since the early 1970s. The near exponential growth of finance and its liberalisation since this point has encouraged this trend. Indeed as we’ll show in this report there are a number of areas of the global financial system that look at extreme levels. This includes valuations in many asset classes, the incredibly unique size of central bank balance sheets, debt levels, multi-century all-time lows in interest rates and even the level of potentially game changing populist political support around the globe. If there is a crisis relatively soon (within the next 2-3 years), it would be hard to look at these variables and say that there was no way of spotting them. Having said that, crises tend to have a large element of unpredictability. If they didn’t then surely more would predict their imminent arrival. So while we highlight a lot of the main global vulnerabilities in this report, history would tell us that there is still a chance that when the next crisis comes its origin will take us by surprise to a certain degree. As will its timing. In the remainder of this executive summary we highlight the conditions that have encouraged crises through history and the main areas of worry as to why we may be vulnerable for another financial crisis relatively soon. Periods with a higher number of crises/shocks coincide with higher levels of debt…. |

Government Debt to GDP, 1884 - 2014 and US Total Debt, 1929 - 2014 |

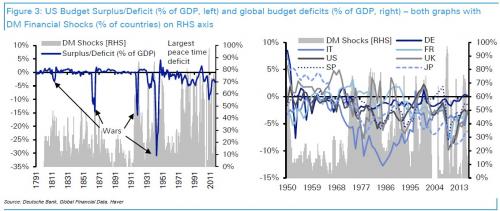

| …and with it higher budget deficits. G7 Government Debt was only previously higher with impact of WWII and before the early 1970s, persistent budget deficits only really existed in war time. Now a permanent feature. |

US Budget Surplus, 1979 - 2011 and Global Budget Deficits, 1950 - 2014 |

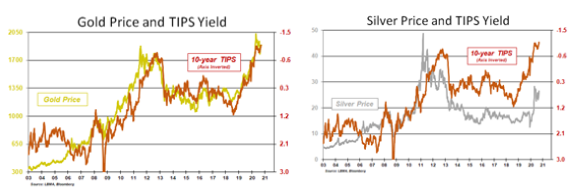

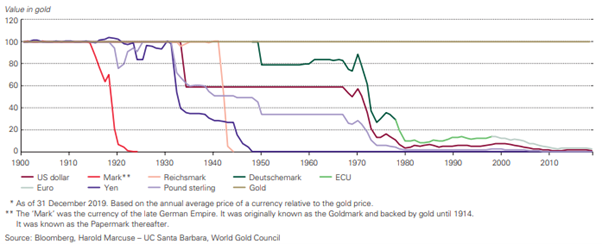

| We think the final break with precious metal currency systems from the early 1970s (after centuries of adhering to such regimes) and to a fiat currency world has encouraged budget deficits, rising debts, huge credit creation, ultra loose monetary policy, global build-up of imbalances, financial deregulation and more unstable markets.

The various breaks with gold based currencies over the last century or so has correlated well with our financial shocks/crises indicator. It shows that you are more likely to see crises/shocks when we break from hard currency systems. |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Daily Market Update,newslettersent