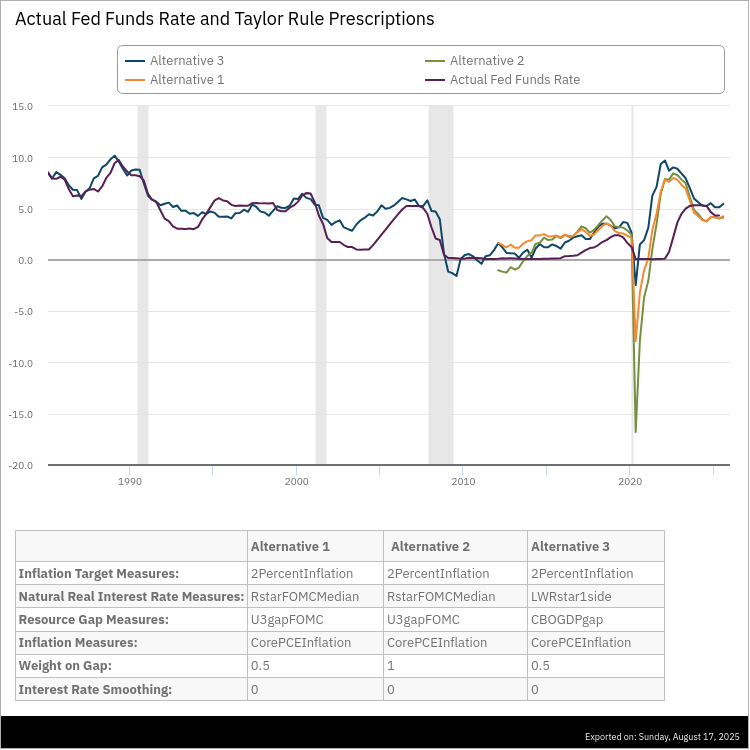

| In early 2005, Greenspan said that the fact that long-term rates were lower despite the Fed’s campaign to raise short-term rates was a “conundrum.” Many rushed to offer the Fed Chair an explanation of the conundrum, which given past cycles may not have been such an enigma in the first place.

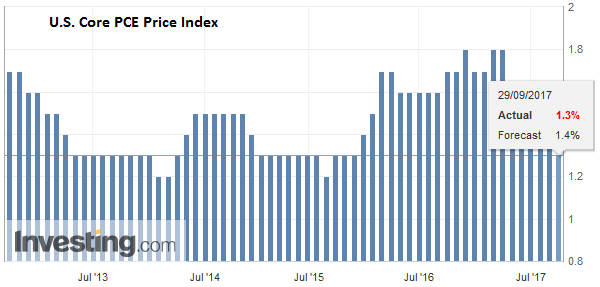

Be it as it may, at last week’s press conference, Yellen admitted that the decline in inflation was a “mystery.” She said, “I can’t say I can easily point to sufficient set of factors that explain this year why inflation has been as low.” However, mysterious the decline in inflation is, Yellen does not appear to be embracing a structural view that has been offered by some of Fed officials, such as Governor Brainard. Yellen is s insists that transitory factors are behind the decline in inflation and that they will diminish over time. She still sounds confident that over time, as slack in the labor market is absorbed, wages will rise, and businesses can be expected to pass on higher costs to consumers. Yellen is interested in a very narrow issue. The core PCE deflator rose from 1.25% in July 2015 to nearly 2% in H2 16 and has subsequently fallen to 1.4%. This is Yellen’s focus. As core inflation firmed, the Fed was feeling more confident about removing some accommodation. By June, opinion frayed. The decline in inflation become more concerning for more Fed officials. |

U.S. Core PCE Price Index YoY (Core PCE Deflator)(see more posts on U.S. Core PCE Price Index (PCE Deflator), ) Source: investing.com - Click to enlarge |

Many have offered to resolve Yellen’s mystery. They cite structural factors, like globalization, demographics, and technological disruptions. The arguments are fine and good but are beside the point. These structural arguments do not explain the recent decline: why the core PCE deflator stood near 1.8% last July and only 1.4% this past July (the most recent reading, until the August report on September 29). It is not very satisfying to receive a long-term structural explanation for a short-term phenomenon.

Some economists have taken a look at the basket of goods and services and found that air travel, apparel, and used car prices have dragged the core measure lower. The appropriate level of analysis is not the integration of China and the former Soviet Union into the market economy. It is not about the Baby Boomers retiring, or unfolding of Moore’s Law.

The chief economist at the BIS, Borio offered his take in a speech last week. He focused on the factors that seemed to have broken down the old relationship between economic activity and prices. Borio offers a clear and compelling explanation: Globalization. The establishment of global value chains and the entry of low-cost producers and their cheap labor into the market economy is at the center of his explanation.

The Financial Times’ Davies see Bario at odds with Yellen. Davies makes it sound that protocol prevented Bario from criticizing Yellen directly for not accepting the structural arguments. But we suggest Bario and Yellen are looking at different things. Bario is looking at the long-term decline interest rates and inflation. Yellen is looking at the last several months.

Moreover, the agreement between Yellen and Bario is of greater significance. The policy prescription is the same, though they arrive at it somewhat differently. Yellen argues that the transitory nature of inflation depressants suggest the Fed should look past them and maintain its course of gradually removing accommodation.

Bario argues that the disinflationary forces, emanating from globalization and technological advances are benign. Officials should accept greater deviation from their point targets of inflation and allow greater time to reach the targets. In the meantime, Bario argues central banks should put more weight on financial stability. Ironically, and Davies sees this, the immediate policy prescription of Yellen and Bario is the same. Continue to raise rates gradually.

In fairness, in recent speeches and FOMC minutes, it seemed to us that the Fed’s leadership was placing more emphasis on financial conditions. The FOMC upgraded its concern about asset prices in July. However, at last week’s press conference, Yellen’s defense of the financial stability mandate was not as robust as it had been. It was somewhat disappointing. We suspect it is a question of emphasis. We will look closely at how financial conditions are addressed, if at all, in today’s speech.

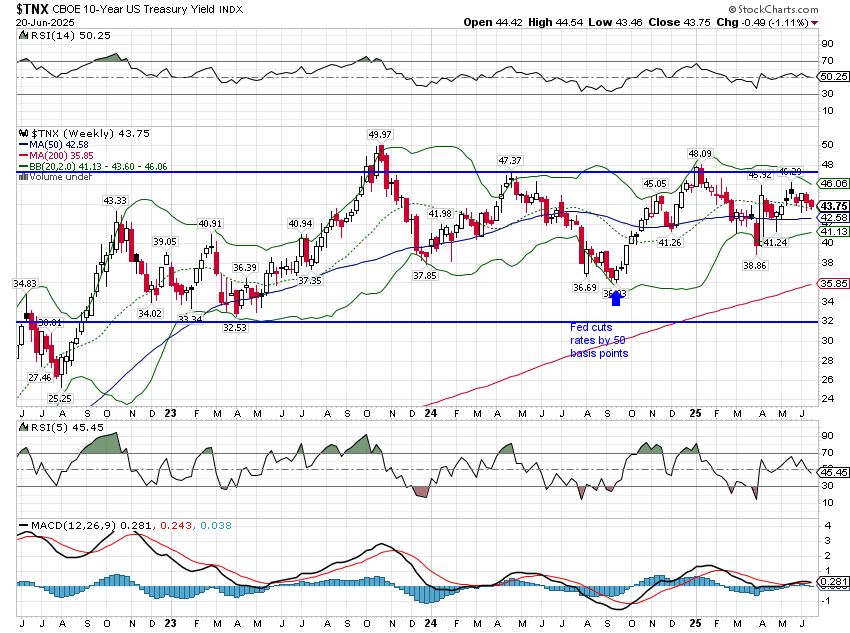

We are struck by the fact that BOE Governor Carney has since he took the job hinted at the need to raise rates nearly every year but last year when they were cut. Once again, he suggested it was possible, and again the market’s ran with it, driving up UK rates and sterling. In contrast, the Fed said last week that it might raise rates three times next year, and the market yawned. Oh., it moved to upgrade the risks of a December hike, The December 2018 contract implies a 1.50% effective Fed funds rate then. The effective average now is 1.16%. A December 2017 hike should bring the effective rate to 1.41%.

In early phases of the recovery, we were skeptical of claims that the Fed lost credibility, but now it seems palpable. The Fed, in effect, has said, that in its judgment, the US economy needs less accommodation. Investors have voted with their pocketbooks, and by driving dollar and interest rates lower and equities higher, they have eased financial conditions. There is a tension here that if the Fed were to fold its cards and capitulate to the market’s judgment, it would be more difficult to rebuild that credibility.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Federal Reserve,inflation,newslettersent,U.S. Core PCE Price Index (PCE Deflator)