A Difference of OpinionsIn his various writings, Murray Rothbard argued that in a free market economy that operates on a gold standard, the creation of credit that is not fully backed up by gold (fractional-reserve banking) sets in motion the menace of the boom-bust cycle. In his The Case for 100 Percent Gold Dollar Rothbard wrote:

Some economists such as George Selgin and Lawrence White have contested this view. In his article in The Independent Review George Selgin argued that it is not true that fractional-reserve banking must always set in motion the menace of the boom-bust cycle. According to Selgin:

However, argues Selgin, no business cycle will emerge if the increase in the money supply is in response to a previous increase in the demand for money:

Likewise in their joint article Selgin and White wrote:

According to this way of thinking the business cycle emerges only if the increase in the supply of money exceeds the increase in the demand for money. |

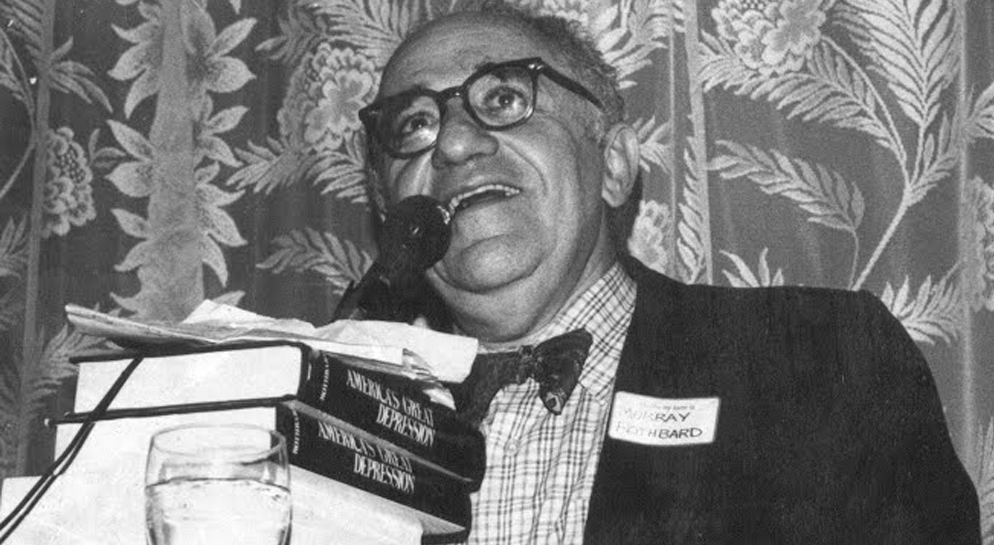

Murray Rothbard was convinced that we should return to a sound monetary system based on the market-chosen money commodity gold. Note that the use of gold as money as such cannot keep banks from issuing fiduciary media (a.k.a. uncovered money substitutes). The important thing is therefore that the monetary and banking system are free. A free banking system will develop along sound lines of its own accord, not least because banks have to continually clear transactions between each other and will tend to shun overextended lenders. A free market monetary/ banking system would likely be different from today’s system in numerous aspects, but it would be just as sophisticated and efficient. Most importantly, it would be economically sound and the likelihood that severe business cycles emerge would be vastly lower. Source: Photo via mises.org - Click to enlarge |

Money Out of “Thin Air” and the Boom-Bust CycleFollowing this reasoning, it would appear that if counterfeit money enters the economy in response to an increase in the demand for money, no harm will be done. The increase in the supply of money is neutralized, so to speak, by an increase in the demand, or the willingness to hold a greater amount of money than before. As a result, the counterfeiter’s newly pumped money will not have any effect on spending and therefore no boom-bust cycle will be set in motion. However, does this make sense? What do we mean by demand for money, and how does this demand differ from the demand for goods and services. Now, the demand for a good is not demand for a particular good as such, but a demand for the services that the good offers. For instance, an individuals’ demand for food is on account of the fact that food provides the necessary elements that sustain an individual’s life and well-being. Demand here means that people want to consume food in order to secure the necessary elements that sustain life and well-being. Also, the demand for money arises on account of the services that money provides. Instead of consuming money, people demand money in order to exchange it for other goods and services. With the help of money, various goods become more marketable — they can secure more goods than in the barter economy. What enables this is the fact that money is the most marketable commodity. An increase in the general demand for money, let us say, on account of a general increase in the production of goods, doesn’t imply that individuals sit on money and do nothing with it. The key reason an individual has a demand for money is that it confers the ability to exchange money for other goods and services. |

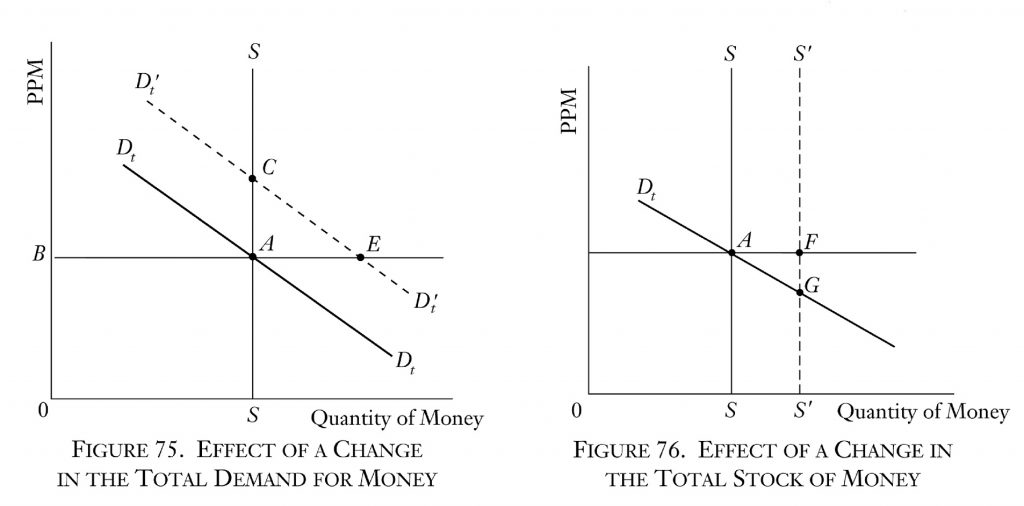

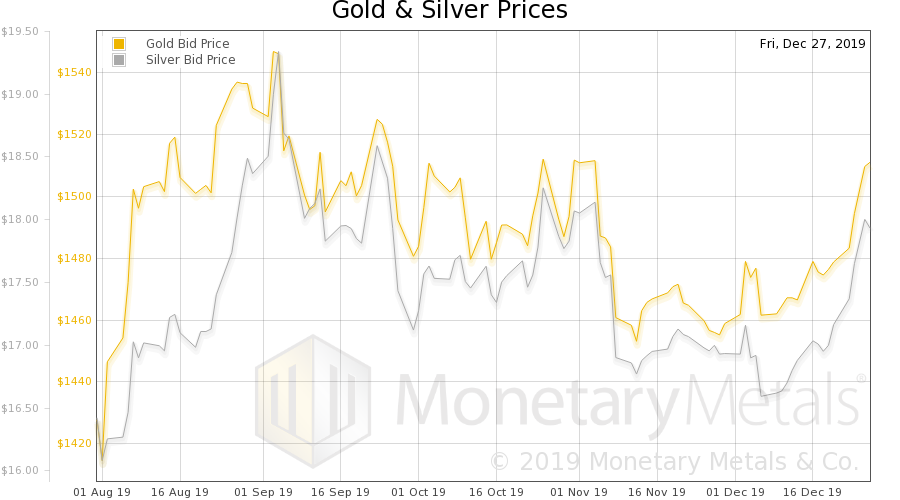

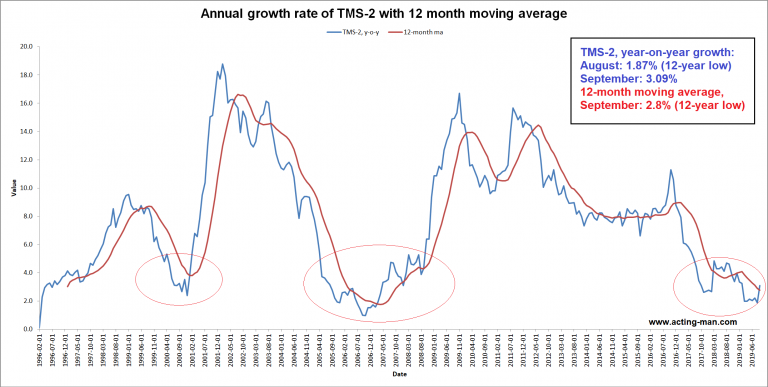

Effect of a Change in the Total Demand for Money Two charts from Rothbard’s Man, Economy and State: the effect of a change in the total demand for money on money’s purchasing power with an unchanged supply (stock of money) and the effect on the PPM of a change in the stock of money (in this case, an increase) while the demand for money remains unchanged. Note though that the effects of altering the money supply by issuance of fiduciary media has much more far-reaching effects than merely changing the purchasing power of the monetary unit. - Click to enlarge |

Individual vs. General Demand for Money

|

Conclusion

We can thus conclude that what sets in motion the boom-bust cycle is the expansion of credit out of “thin air”, regardless of the state of the general demand for money. Again, irrespective of whether the total demand for money is rising or falling, what matters is that individuals employ money in their transactions.

As we have seen, once money out of “thin air” is introduced into the process of exchange this lays the foundation for the boom-bust cycle.

We can further infer that it is not the failure to accommodate the increase in general demand for money that causes an economic bust, but actually the accommodation by means of money out of “thin air” that does it.

References:

(1) Murray N. Rothbard, The Case For A 100 Percent Gold Dollar (Cobden Press 1984)

(2) George Selgin, “Should We Let Banks Create Money? ” The Independent Review (Summer 2000): 93–100

(3) George Selgin and Lawrence White, “In Defense of Fiduciary Media; or, We Are Not Devolutionists, We Are Misesians! ” Review of Austrian Economics 9 (1996): 83–107.

Charts by Murray N. Rothbard

Chart and image captions by PT

Note by PT: we have edited the original text very lightly in a few spots. Also, the emphasis on two sentences under the sub-heading “Money Out of “Thin Air” and the Boom-Bust Cycle” has been added by us, in order to highlight what we believe to be important points (all other emphasized passages are in the original).

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Murray Rothbard,newslettersent,On Economy

1 comments

Michael Wolf von Babo

2017-01-13 at 17:06 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

Interesting. But how do you accomodate the increased demand for money – i.e. following a technical innovation/new market – then, without a (too big) increase in interests?