Investors are familiar with a broad set of macroeconomic variables that often drive asset prices. Many are familiar with corporate balance sheets, price-earning ratios, free cash flow, Q-ratio, and the like.

However, political factors are more difficult for investors to integrate into their analysis. Therein lies the main challenge in the year ahead. There will be many opportunities for political factors to overwhelm economic considerations. This past year gave a an inkling of what is possible with the UK decision to leave the EU and the election of Donald Trump as the next US president, both of which surprised many.

Perhaps what is even more surprising is what happened next. The sharp depreciation of sterling was anticipated, though the speed of the adjustment may have caught many off-guard. The UK economy fared better than some economists had anticipated, though the aggressive central bank response may have helped. In addition to the stimulus provided by an 11% decline in the 100-day moving average of sterling’s broad trade-weighted index, the Bank of England cut the base rate, provided cheap funding for banks, and resumed its sovereign bond-buying program, including corporate bonds for the first time. The economy maintained its forward momentum.

The markets responded enthusiastically to the unexpected outcome of the US election. Interest rates, especially the long-end of curves, including the US Treasury market, sold off dramatically. The steepening of curves is what many high-income countries wanted but could not engineer. Despite the sharp rise in interest rates, equity markets rallied strongly though the composition and leading sectors changed. The dollar rose sharply against nearly all currencies, including G10 and emerging markets.

Other forces were pushing in the same direction. There was mounting evidence that China’s economy was stabilizing with the help of even more debt. Saudi Arabia abandoned its new strategy and returned, it would appear, as the swing producer, forging a deal with its rivals, Iran and Russia. Also, the inventory and manufacturing headwinds on the US economy abated. After three quarters of sub-trend growth (Fed estimates at 1.8%), the US economy accelerated to 3.2% in Q3 ‘16, the fastest pace in two years. It is also the fourth strongest quarterly growth since the beginning of 2010, and Q4 is tracking above trend as well.

At the same time as investors are having to navigate individual events, there is a sense of a larger wave that is washing across the world. It is populism-nationalism, the link between Brexit and the US election. Ironically, these are two economies that have emerged from the Great Financial Crisis in the best shape. Policymakers aggressively responded to the crisis and both countries were near full employment. Growth was steady even if not spectacular. The populist-nationalist forces are on the rise in Europe, and they are particularly potent because the EU and EMU are essentially projects that require integration and some surrender of sovereignty in exchange for strategic goals, like greater chances of peace and prosperity.

Eurozone

There are three elections slated in the EU next year, and there could be a couple more. The Dutch election will be held in March, the first round of the French Presidential election in April, and the German general election in September. There is a reasonably good chance that Italy will also have elections, though the parliament session does not officially end until 2018. Snap elections in Greece are relatively common, and although the current parliament can sit until 2019, Prime Minister Tsipras may be seeking an opportunity to renew his mandate.

Of the scheduled elections, France has drawn the most attention. The populist-nationalist forces are running strong, and the two main political parties have their own convulsions. On the center-right, the primary contest was between three former prime ministers, Juppe, Sarkozy, and Fillon. Fillon, who says he wants to do for France what Thatcher did for the UK, won handily.

On the Socialist side, the unpopular incumbent Hollande is not seeking reelection. The left-wing of the party is likely to be pushed aside by its own centrists. Former Prime Minister Valls will likely carry the Socialist Party mantle, while former Economic Minister Macron runs as an independent, thus splitting an already weakened position.

The polls show Fillon beating Le Pen in the second round. It is part of France’s political tradition for the main two parties to support each other in the face of a strong challenge by the National Front. In some ways, the price of defeating Le Pen now may be the shifting of the French political discussion to the right.

The Dutch do not have such a tradition and their national election is before France. The populist-nationalist Freedom Party is ahead in the polls. It has recast itself much as Le Pen has tried to do to the National Front, moving away from anti-Semitism and homophobia and haranguing against the perceived threat of Islam and Brussels.

Perhaps the most powerful check comes in the form of having many parties in a proportional representative system. This forces coalition, and would make it extremely difficult for the Freedom Party to govern as none of the other parties are willing to join it. That said, it is possible that the polls in the Netherlands, like many in the UK and US, fail to recognize the strength of the populist-nationalists. If the Freedom Party can win a majority or is close enough that a small party can be offered a plumb reward to secure a majority, it will be difficult block it.

Germany

Germany’s Merkel is already tacking right to steal some thunder from the rising AfD Party, which is also pushing an anti-EMU and anti-immigration line. While the AfD will most likely be represented in the next parliament, it is unlikely to challenge the duopoly of power of the CDU/CSU and SPD. Although the forces of movement appear to be in ascendancy, in Germany the continuation of the status quo is the most likely scenario. If the two main parties fail to secure a majority, the Freedom Democrats (FDP), which had self-immolated during the initial stages of the crisis, will be reborn.

With the defeat of the referendum seeking to change the size and function of the Italian Senate, Prime Minister Renzi resigned, and former Foreign Minister Gentiloni became Italy’s fourth successive unelected Prime Minister. The two pressing challenges are the fragile banks – burdened by bad loans, weak growth, and excess capacity – and preparing for elections.

The previous electoral law was ruled unconstitutional. The new electoral law for the lower house will be reviewed by the Constitutional Court in late January. At present, there is no electoral law in place for the Senate. The caretaker government needs to resolve these issues. An election in Q1 ‘17 seems unlikely. An election around midyear is more likely, but it is possible that Gentiloni stays a bit longer.

United KingdomWith a slim majority, the British people voted to leave the EU. Exactly what it means is not clear. Europe insists that the price of single market access is accepting the EU’s immigration policy. European officials need to tread carefully. They need to be hard enough on the UK to provide an undesirable example for other countries that might be contemplating leaving. At the same time, they cannot be so tough as to prevent cooperation with the UK on other fronts.

Prime Minister May wants to trigger Article 50, which begins the formal negotiations of the separation, by the end of Q117. There is an additional legal complexity because the extent that May can claim the royal prerogative is disputed. The Supreme Court is expected to make a ruling in the middle of January. There may be other legal challenges that could cause future delays.

The issue is being framed as a hard or soft Brexit. A hard Brexit is the loss of access to the single market. It gives priority to limiting immigration. The market responds to developments that increase the risk of a hard Brexit by selling sterling.

A soft Brexit secures access to the single market. Parliament is understood to be less inclined to support Brexit than the population as a whole did. The larger the role of parliament, the more likely a soft Brexit. If triggering Article 50 is delayed, or if a protracted transition state can be negotiated, it may also be supportive for sterling.

The sharp decline of sterling on a trade-weighted index has already begun feeding through to higher inflation. The Bank of England is unlikely to respond to firming prices, accepting that the devaluation is a one-off, temporary boost to prices. The improvement in trade may take longer and be less pronounced than the impact on prices Nevertheless, the decline of sterling, alongside the monetary and mild fiscal support, should keep the economy humming in the first half of the year. However, in the second half, the impact is likely to moderate.

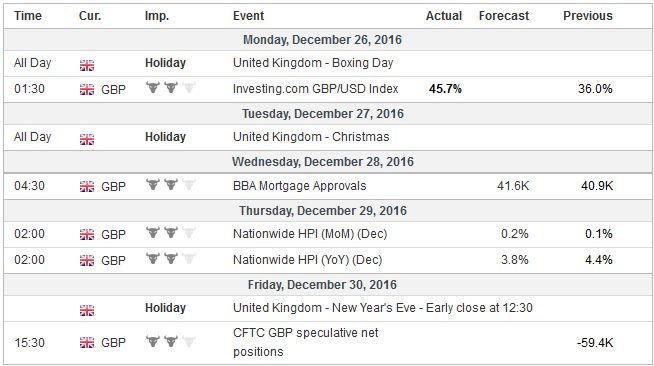

|

Economic Events: United Kingdom, Week December 26 |

United StatesA new and unorthodox administration will formally take office in late January, but Trump’s impact is already being felt. The equity and bond market response to the election results is largely in line with the market’s response to Reagan’s election in 1980. The dollar has outperformed.

Our dollar bullish view was based on the significance we attributed to financial and monetary divergence. On top of that, we place the more precarious European political situation. Then, as the US primaries unfolded, it became increasingly clear to us that whoever won, fiscal policy would become easier.

Having experienced the Reagan-Volcker dollar rally and the Deutschemark overshoot following the unification of Germany (which incidentally created a crisis for which monetary union was the proposed solution), we quickly recognized that the new policy mix is best for a currency–easier fiscal policy and tighter monetary policy. It reinforced our bullish case for the dollar.

It is not clear how much of what was said during the campaign was aspiration policy, declaratory policy, or operational policy. Also, it is not clear the extent to which the Republican Party in the legislative branch will cooperate with the Republican Party in the White House. President-elect Trump may find that the Democrats can support the infrastructure spending efforts, while the Republicans can support tax cuts.

There are many unknowns, but the market seems to be anticipating lower corporate taxes, easier regulation, and better profits. It is also anticipating somewhat higher inflation and an accelerated timeline for gradual normalization of US monetary policy. During the campaign, President-elect Trump was critical of Yellen and the Federal Reserve. Investors may be pleasantly surprised to find that in office, Trump will likely respect the independence of the Federal Reserve.

Trump will likely be able to mold the Federal Reserve into the central bank he wants. There are currently two vacancies on the seven-member Board of Governors. Of those, it is assumed one will become the Chair when Yellen’s term expires in February 2018. Vice-Chairman Fischer’s term ends in June 2018.

One of Trump’s initial appointments could be, as required by Dodd-Frank legislation, a Vice-Chairman for regulation (even if it is later replaced). This function has been filled by Governor Tarullo, who some expect to resign when the new role is filled. There is also some speculation that Governor Brainard, who was thought to be a possible Treasury Secretary in a Clinton administration, may also step down. The point is that within a little more than one year in office, Trump’s appointments could constitute a majority of the Board of Governors.

In 2017, we expect Yellen to continue to normalize the Federal Reserve’s monetary policy. The December FOMC meeting resulted in a rate hike, and economic projections anticipate that three rate hikes would be appropriate in 2017. This is not a commitment, of course, and it does not include any potential changes to fiscal policy.

We would place the risk on the upside. The Fed’s objectives of full employment and 2.0% core PCE deflator are within view. Somewhat quicker tightening may be forthcoming if wage growth is evident and sustained. We do expect some fiscal stimulus even if it is not the $1 trillion that has been widely discussed. That said, rapid dollar appreciation, on a real trade-weighted basis, might give the Fed pause, especially if stronger world demand does not materialize.

The Federal Reserve is unlikely to preemptively turn more aggressive even when the new president provides more details of his fiscal intentions. It is only prudent and practical to see what is eventually negotiated, and when it is implemented. If the economy is going through a soft patch, for example, as it appears to have exited near midyear, the fiscal stimulus could be delivered at an opportune time. On the other hand, if the unemployment rate is threatening to fall below 4%, the economy is growing above trend, and prices are accelerating, a different response may be necessary.

As a candidate, Trump, like Obama and Bush before him, threatened to cite China as a currency market manipulator on day one. Indeed, the indication is that currency and trade will be the first priority of the new administration, with taxes and infrastructure spending addressed later on.

|

Economic Events: United States, Week December 26 |

China

Recall that if China is judged to be a currency manipulator, bilateral talks must be held, and US companies can sue for damages. Under direction from Congress, the US Treasury has developed a quantifiable definition of manipulation. China has not met it. Neither Obama nor any other president before him for over twenty years has formally declared China to be a manipulator. Any reasonable definition of currency manipulation that can be applied to China would likely apply to many other countries.

It is true that China has been intervening in the foreign exchange market, but it is to strengthen not weaken the currency. The more than one trillion dollars in reserves that the central bank has drawn down is reflective and suggestive of the immense capital outflows it is experiencing. If Chinese officials were to step away and let the market determine the exchange rate, which the G7 and G20 have endorsed, the yuan would likely fall fast and furious.

Later it would intensify trade tensions, as the products of China’s vast excess capacity would export. At the end of 2016, the US placed anti-dumping duties on Chinese-made washing machines and opened a new investigation into plywood imports from China. Both China and the US (and nearly every other country) are members of the World Trade Organization. The rules are established, and there is a conflict resolution mechanism. Clearly, the risk is that the Sino-American relationship is tested in the period ahead, but the status quo is not particularly robust.

Chinese politics will also be important next year. There is no need to confuse politics and political parties. China may only have one political party, but its politics are as serious and intense as any place, though perhaps more subtle. President Xi has been gradually consolidating power. He is perceived as China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping.

While President Xi is overseeing the continued modernization of the Chinese economy, the political structure, if anything, has become more rigid. Many suspect that the anti-corruption campaign was primarily aimed at political targets. Xi appears to have tightened political control over society, including the toppling of some internet personalities, and limited civil rights expressions.

The 19th Party Congress toward the end of 2017 is important. The key seven-member Standing Committee is set for a complete overhaul with only President Xi and Premier Li holding on to their posts for a second term, which has become customary in China. There are two aspects that will be closely watched. First, Xi’s successor is likely to be one of the new members. Second, there has been respect for the “seven up, eight down” rule, which means that if a member of the Standing Committee is 68 at the time of the Congress, he must retire, but a 67-year-old can still become a member. If an exception is made, it could spur speculation that Xi himself may seek a third term or retain extensive formal power after the second term ends.

China’s economy appears to have stabilized, but the cost is increased debt levels. In addition, the powerful forces spurring capital outflows, among which are corporations paying down their dollar debt, have prompted Chinese officials to tighten capital controls. It is a precarious balancing act that does not leave much margin for error.

At the same time, our long warning that the past appreciation of the yuan flattered measures of its globalization is being borne out in recent data, though it is now a member of the IMF’s SDR. The share of foreign trade settled in yuan has fallen from 26% to 16% over the past year. Yuan deposits in Hong Kong are off 30% from their 2014 peak (CNY1 trillion). Foreign ownership of domestic Chinese assets peaked in 2015 near CNY4.6 trillion and has fallen to CNY3.3 trillion as of the end of Q3 ‘17. The yuan itself has surpassed the Mexican peso as the most actively traded emerging market currency, but overall it is the eighth most traded currency, putting it between the Swiss franc and Swedish krona. In 2013, it was in ninth place.

The Dollar

Our broad outlook for the dollar remains intact. It is predicated on the divergence of monetary policy and interest rates. The traditional knock on the US, that having the dollar as the major reserve currency gives it an exorbitant privilege of lower interest rates, misses this key driver. The US premium over Germany, the UK, and Japan are at multi-year extremes. This creates an incentive structure that encourages investment flows into the US and hedging non-dollar exposure.

On top of the monetary divergence, which, in our conception, is sufficiently encompassing to include the health of financial institutions, is the policy mix. A trajectory of tighter monetary policy and looser fiscal policy is associated with currency appreciation. This was the policy mix under Reagan-Volcker and in Germany when the Berlin Wall fell, and the country was reunited.

Also, we are concerned that political events, not just what we outlined above but those continuing over the next few years, are going to challenge the foundation of the European project. In the not-too-distant future, investors are going to have to contemplate a post-Merkel Germany and a post-Draghi ECB. To be sure, these developments are not imminent, but for long-term investors, the European outlook is particularly concerning.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: China,Europe,Federal Reserve,newslettersent,Politics,US