- Currency stability is a prerequisite for China's economic transition

- Defending the yuan is prohibitively expensive – China cannot beat the market

- Progressive devaluation managed by PBoC is the most probable scenario for 2016

- Remember that the country is on the capitalism learning curve

- Exchange rates will inevitably be a key discussion point at Shanghai G20

- China has moved from being a net importer to a net exporter of capital

Shoring up a currency ad infinitum is impossible. The market always wins.

The undervalued Chinese yuan is nothing but a bad memory. In the context of competitive devaluations throughout the world, the yuan is now significantly overvalued compared to its main counterparts, primarily the dollar and the euro.

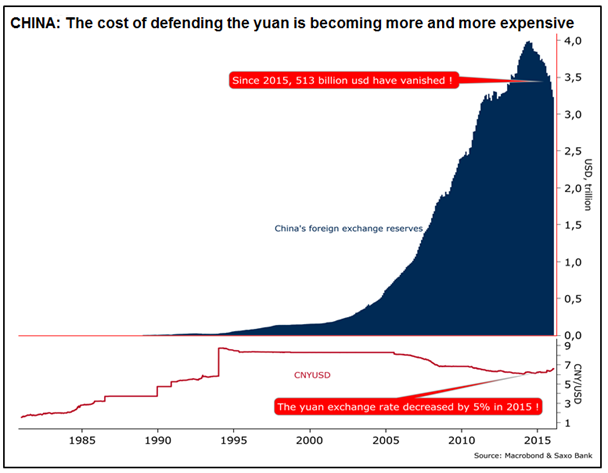

If it is to pull off its economic transition, China needs a stable currency, hence its repeated interventions on the exchange markets over the past few months. Over the last year $513 billion was drawn from the foreign exchange reserves without stemming any of the downwards market pressures on the yuan. Over the period is actually lost 5% against the US dollar. This is a significant depreciation for a currency that is used to fluctuating between narrower markers. By way of comparison, the euro, which floats freely on the market, lost almost 6% of its value against the US dollar last year.

The increasingly credible assumption of a devaluation before this summer:

Shoring up a currency ad infinitum is impossible. The market always wins.

The undervalued Chinese yuan is nothing but a bad memory. In the context of competitive devaluations throughout the world, the yuan is now significantly overvalued compared to its main counterparts, primarily the dollar and the euro.

If it is to pull off its economic transition, China needs a stable currency, hence its repeated interventions on the exchange markets over the past few months. Over the last year $513 billion was drawn from the foreign exchange reserves without stemming any of the downwards market pressures on the yuan. Over the period is actually lost 5% against the US dollar. This is a significant depreciation for a currency that is used to fluctuating between narrower markers. By way of comparison, the euro, which floats freely on the market, lost almost 6% of its value against the US dollar last year.

The increasingly credible assumption of a devaluation before this summer:

Three possible scenarios exist for the Chinese yuan in 2016:

Three possible scenarios exist for the Chinese yuan in 2016:

- The progressive devaluation managed by the People's Bank of China

- Continued defence of the currency on the markets

- New Plaza-type Accord

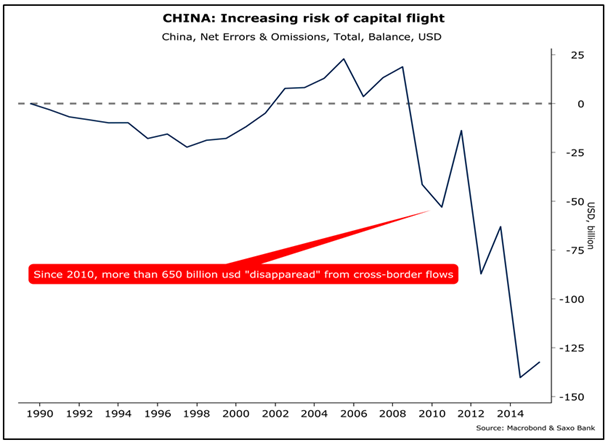

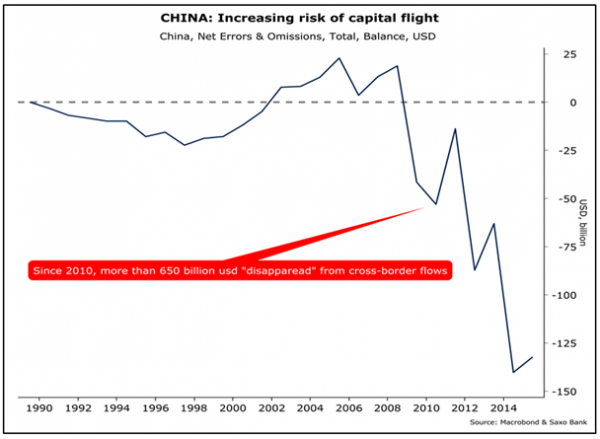

The fall of the yuan is closely correlated with capital outflows. This is difficult to measure precisely given the opaque way in which Chinese statistics are calculated. Our low estimate leads us to conclude that almost 650 million dollars in capital have flowed out of the economy since 2010, based on the change in the "net errors and omissions" in the trade balance. The actual total amount is certainly much higher, but this estimate confirms that contrary to what was commonly admitted, China has moved from being a net importer to net exporter of capital. Despite the 4,000 billion yuan recovery plan presented at the end of 2008, China has not managed to sufficiently strengthen its economy. Regardless of which is PBoC's preferred scenario, when it comes to stabilising the exchange rate for the yuan, capital outflows must inevitably be restricted.

It would not be a good idea to implement the capital controls alluded to, since this would send a very negative message to foreign investors at the worst possible time. In addition, past experience shows that gaps can always be found in such measures in order to transit capital out of the country through indirect means, such as via Hong Kong, in China's case. For true effectiveness, strict controls are required which would result in the economy being completely stifled. This makes absolutely no sense in this case. China will have no other choice in the years to come, but to offer liberalisation guarantees to foreigners for the domestic capital market and strengthen its financial regulations, which are still very inadequate.

This long process does not exclude new significant corrections on the Chinese stock market or even business bankruptcies that will result in reducing the moral hazard. Nevertheless, what is certain is that a stable exchange for the yuan after devaluation could help reassure market players. This is after all, the simplest and quickest way to proceed. China does not have any other credible, effective levers to restore balance to its economy in the short-term.

The fall of the yuan is closely correlated with capital outflows. This is difficult to measure precisely given the opaque way in which Chinese statistics are calculated. Our low estimate leads us to conclude that almost 650 million dollars in capital have flowed out of the economy since 2010, based on the change in the "net errors and omissions" in the trade balance. The actual total amount is certainly much higher, but this estimate confirms that contrary to what was commonly admitted, China has moved from being a net importer to net exporter of capital. Despite the 4,000 billion yuan recovery plan presented at the end of 2008, China has not managed to sufficiently strengthen its economy. Regardless of which is PBoC's preferred scenario, when it comes to stabilising the exchange rate for the yuan, capital outflows must inevitably be restricted.

It would not be a good idea to implement the capital controls alluded to, since this would send a very negative message to foreign investors at the worst possible time. In addition, past experience shows that gaps can always be found in such measures in order to transit capital out of the country through indirect means, such as via Hong Kong, in China's case. For true effectiveness, strict controls are required which would result in the economy being completely stifled. This makes absolutely no sense in this case. China will have no other choice in the years to come, but to offer liberalisation guarantees to foreigners for the domestic capital market and strengthen its financial regulations, which are still very inadequate.

This long process does not exclude new significant corrections on the Chinese stock market or even business bankruptcies that will result in reducing the moral hazard. Nevertheless, what is certain is that a stable exchange for the yuan after devaluation could help reassure market players. This is after all, the simplest and quickest way to proceed. China does not have any other credible, effective levers to restore balance to its economy in the short-term.

Curiously, progressive devaluation would actually aid the internationalisation of the yuan.

Full story here

Are you the author?

Previous post

See more for

Next post

Curiously, progressive devaluation would actually aid the internationalisation of the yuan.

Full story here

Are you the author?

Previous post

See more for

Next post

Tags: central banks,China,Hong Kong,Japan,Monetary Policy,recession,recovery,Swiss National Bank,Trade Balance,Volatility,yuan