In many ways, the world has turned upside down. It is not just central banks that have set policy rates below zero, but the entire German curve out through eight years have negative yields. Japan, which has the largest debt burden relative to GDP, has negative yields out through nine years. The Swiss curve is negative through 15 years.

It is not just core countries either. Ireland, which holds national elections in a couple of weeks, has negative yields out four years. Spain, which is struggling to put together a government following the election at the end of last year, has negative rates through two-years.

Another aspect of the world that seems to be turned on its head is that several central banks and governments want businesses to give workers bigger wage increases. This is important. Many observers think that the role of central banks is to protect banks. This is to confuse means and ends. Central banks recognize that a healthy financial system is necessary for a robust economy, but it is the general economic performance that is the goal.

Japan offers the most timely illustration of this generalization. Although higher wages were not one of Abe's initial three arrows, it was recognized from the start that higher wages were necessary to boost growth and finally arrest deflation. The failure to ensure higher wages has undermined Abenomics.

Cash earnings in Japan were expected to have risen 0.7% year-over-year in December. They did not. They rose by a meager 0.1%. This is slower than in 2014. Annual wage growth has not surpassed 1% since 1997. When adjusted for inflation wages in Japan have not risen since 2011. Remember too that 1 April 2017 Japan is planning on hiking the retail sales tax from 8 % to 10%.

Japan's trade union confederation (RENGO) is seeking 2% wage increases in the spring negotiating round. This is a soft demand. Even if it were to get it, which it much likely won't, it would not be enough for the BOJ to reach its 2% inflation target. For that, a 3% increase in wages is thought to be necessary. Finance Minister Aso has urged the unions to demand 3-4% increases.

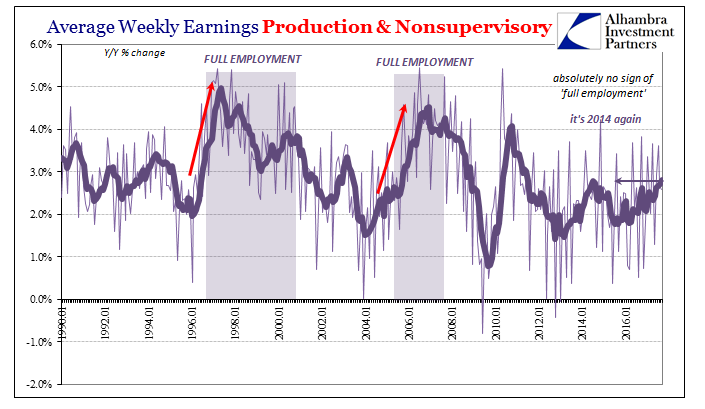

In the UK too, the lack of wage increases has deterred the Bank of England from raising interest rates. The rise in earnings in the middle of last year were not sustained and seemed to have been a bit a statistical quirk. Average weekly earning had fallen 0.1% in the middle of 2014 on a three-month year-over-year measure. In May 2015, it had risen to 3.3%. This is what prompted many to expect a BOE hike first in 2015 and then in early 2016. It has been pushed out into 2017 as average weekly earnings slumped to 2.0% in November. The December figures will be released next week. Several MPC members have indicated that until there is better traction on wages, they are hard pressed to support higher interest rates.

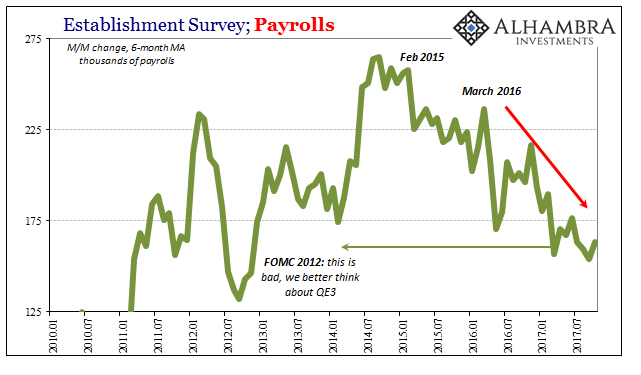

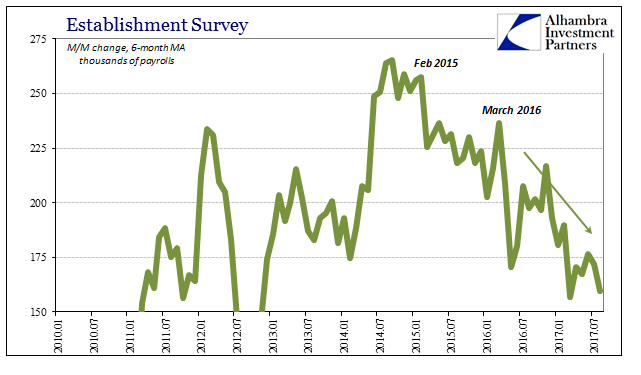

The US government and Federal Reserve are also encouraging higher wages. The Federal government has hiked the minimum wage it pays as well as its contractors. Many state and local governments have raised minimum wages. The Federal Reserve bases its argument that inflation will move toward the target because it expects the reduced slack in the labor market will push wages higher. Wages, in the Fed's thinking, is the key to core inflation. They understand that headline inflation converges with core inflation and not the other way around.

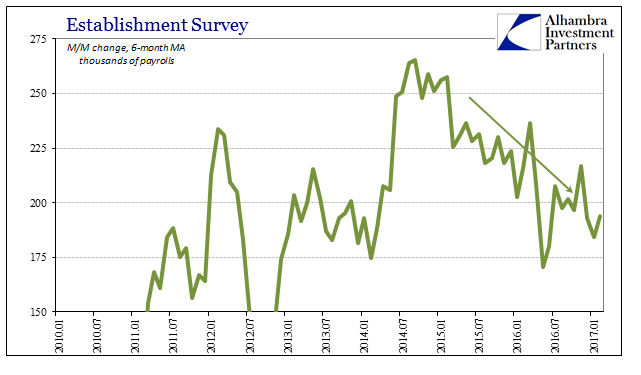

The US appears having the most success in achieving higher wages, but even here it is modest only recently has it shown movement in the desired direction. The January jobs data released before the weekend showed an unexpected 0.5% rise in hourly earnings. This translated into a 2.5% year-over-year pace. Although it was slower than the revised 2.7% pace reported for December, the December-January period was the strongest two months for earnings growth since Q3 2009.

The ECB seems to be a bit of an outlier. Cutting wages was part of the solution that the creditors imposed on countries seeking formal assistance. Draghi has argued though that lackluster wage growth (and rising concerns about low inflation) justifies more action by the ECB. If wages were rising more robustly in the eurozone, Draghi's case for more unorthodox policies would be weaker.

There are normative claims about wages as well. The disparity or wealth and income are arguably increasingly recognized as a threat to sustaining aggregate demand, and a healthy economy more generally. At the same time, raising wages faster than productivity increases will squeeze profits.

It seems to be a testimony to the strange world we live in where interest rates can fall below zero (and not just administered rates), and officials encourage wage increases. The reluctance of Japanese companies to share their record profits in the form of higher wages is frustrating the Japanese government, but it is reluctant to take stronger action, such as raising the tax on retained earnings, or narrowing stocks that the BOJ buys under QQE to only those companies raising wages by more than 2%.

While many countries want higher wages, they are not encouraging the strengthening of those organizations (e.g. labor unions) that specifically push for higher wages. As part of the recovery from the Great Depression, countries, including the US did facilitate unionization.

Tags: U.S. Average Earnings