In summer 2013, even the sceptical and “gold-friendly” economist John Mauldin followed the mainstream thinking that fracking and other technology could reduce OPEC’s and the Chinese’s advantage in global trade and reduce the U.S. trade deficit. Recently both claims got refuted: the first with WTI crude oil prices rising to nearly 108$ despite enhanced supply. Detailed data showed that rising U.S. industrial production was not caused by more manufacturing but by mining and the oil industry. We think that any way the U.S. current account deficit could effectively shrink. The reason, however, is that the savings rate of Americans could rise further and the balance sheet recession continue. Traditionally currencies appreciate with higher savings (in local currency) and depreciate with more spending.

We start with extracts from John Mauldin, The Renminbi, Soon To Be a Reserve Currency, written end of September 2013.

He describes the two cycles that could be disrupted by the end of the U.S. trade deficit:

(1) The exchange of US dollars for OPEC oil.

(2) The exchange of US dollars for Asian manufactured goods.

The US energy boom in shale oil and gas. The US has caught an incredibly well-timed “lucky break” made possible by the combination of new exploration, production, and processing technologies (such as horizontal drilling and fracking) and by the serendipitous discovery of massive supplies of oil and gas, often in areas that already have significant infrastructure and/or are accessible at reasonable costs. This energy renaissance is part of the reality that has made Houston, Texas, the number one port in the United States, with even more growth coming in the near future when the Panama Canal expansion is completed in 2014. US manufacturers are turning less-expensive oil and gas into value-added fossil fuel products and exporting them to the world.

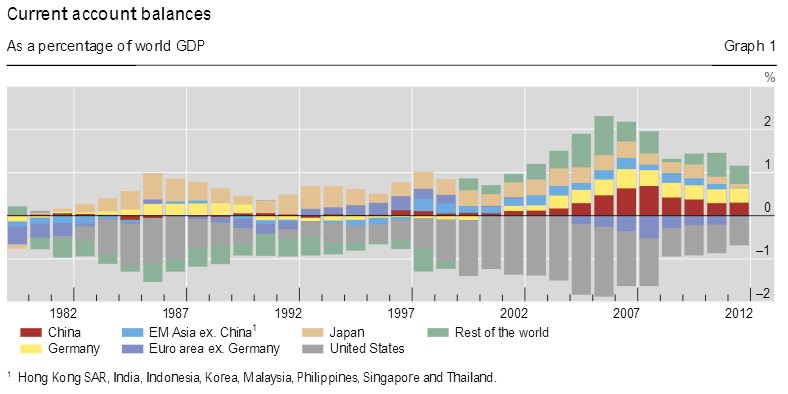

By definition, a shrinking US current account deficit also means falling liquidity around the world (since the USD makes up one side of the trade in 87% of global currency transactions); and, as our friends at GaveKal have argued for years, a falling US current account almost always means that we will see a crisis somewhere in the world Should the US achieve a positive trade balance, that shift would have a BIG impact on the rest of the world.

For starters, moving from a current account deficit to a current account surplus will disrupt the two most important trade relationships in the world today:

(1) the exchange of US dollars for OPEC oil, and

(2) the exchange of US dollars for Asian manufactured goods.And while the US will continue to import significant (one could even say huge) quantities of manufactured goods, the quantity of dollars moving permanently offshore will be significantly reduced.

With the US current account deficit continuing its fall, we need to be alert for the next crisis abroad. It is very difficult to predict exactly when, where, and how markets will panic, but taking US dollars out of the trading system is akin to losing a chair in a game of musical chairs. Someone is going to be left out. It could be Europe or Japan – there are more chapters to come in the sordid European and Japanese economic sagas – but more likely it will be emerging-market countries loaded with a lot of external debt denominated in US dollars who struggle to keep a seat at the table.

Emerging markets, particularly Asian and Latin American economies, took a beating during the 1990s precisely because of boom-and-bust credit cycles caused by hot capital inflows followed by rapid capital outflows. This volatile boom/bust cycle is precisely what emerging-market policy makers were hoping to forestall by holding larger foreign exchange reserves starting in the late ’90s, but trading predominantly in the US dollar left them to vulnerable to swings in market interest rates and Fed policy.

I did an extended interview with Louis Gave this past Monday on BNN, the national Canadian business network…. Let me offer a rough transcription of what he said. I had just commented on my belief that the US is on its way to a positive trade balance, which will make the dollar remarkably strong. The corollary is that there will be fewer dollars available to the world for global trade. Then Louis jumped in:

I think it [a positive US trade balance] is a very important development for the part of the world I come from. I live in Hong Kong. Asia up to now has mostly been a US dollar zone. In Asia we basically produce manufactured goods, sell them to the US, and earn the US dollars we need to trade with one another. So when China trades with Indonesia, the trade is denominated in dollars. When Japan trades with Taiwan, that trade is denominated in dollars.

The big issue is, if we move into a world where the US current account deficit disappears – both through the energy revolution that the US is going through and the consequent manufacturing renaissance – then, all of the sudden, manufacturing in the US is a lot cheaper than elsewhere because the cost of energy is so much cheaper. If the US basically imports [brings back] all of its manufacturing and no longer exports US dollars, how will Asia trade with itself? And how will emerging-market trade grow if they don’t earn the dollars?

So far John Mauldin, but at the end of June 2014, the WTI crude oil price had risen to 108$: the effects of increased fracking supply are not really visible. In the 1980s, however, the oil glut sustained strong growth. We strongly doubted that shale oil could really be a game changer, in particular because production costs in the U.S. are far higher than in the OPEC countries. Moreover, we think that oil prices will always go up; rising global demand is able to outweigh higher supply: just the speed of price adjustment might be lower than previously.

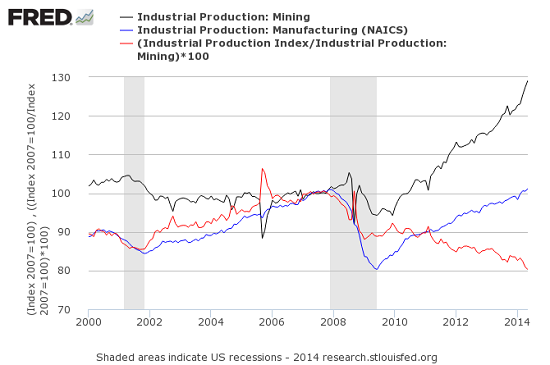

Charles Hugh Smith refuted the idea that the U.S. has become more competitive in manufacturing and showed that most of the parts of higher industrial production originated from mining that includes the oil industry, as follows:

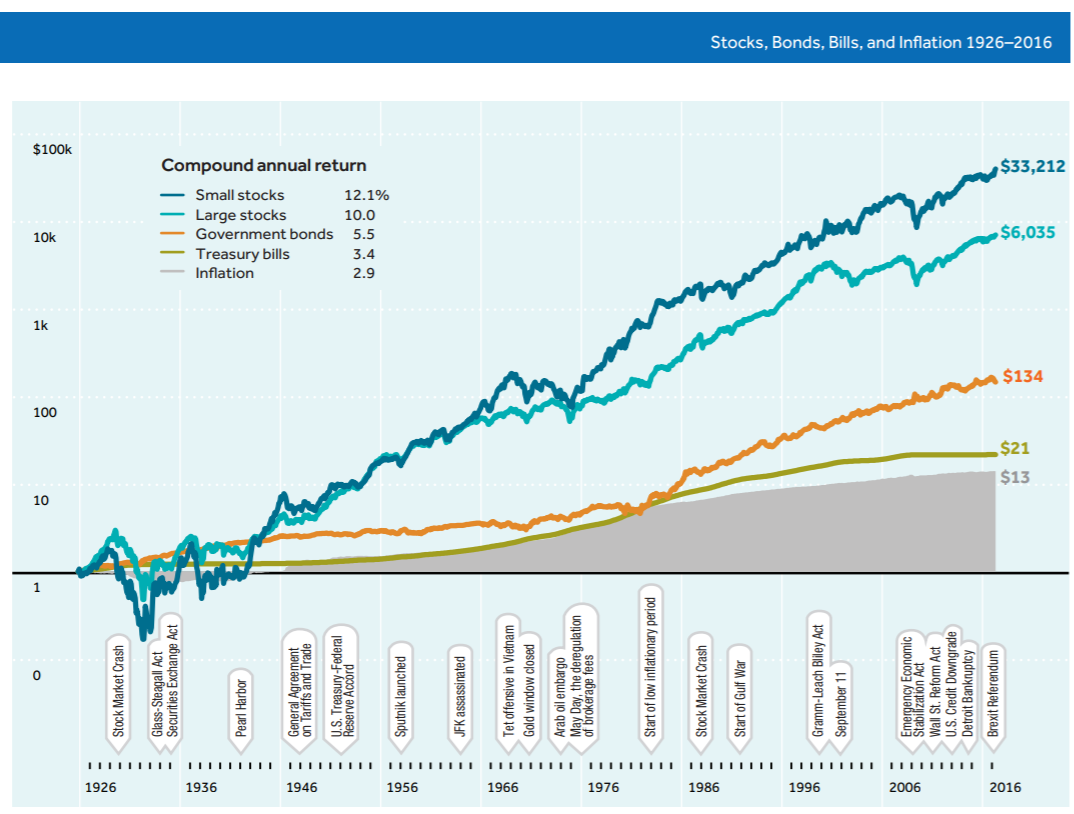

In summer 2013, even the sceptical and "gold-friendly" economist John Mauldin followed the mainstream thinking that fracking and other technology could reduce OPEC's and the Chinese advantage in global trade and reduce the U.S. trade deficit. Recently both claims got refuted: the first with WTI crude oil prices rising to nearly 108$ despite enhanced supply. Detailed data showed that rising U.S. industrial production was not caused by more manufacturing but by mining and the oil industry. We think that any way the U.S. current account deficit could effectively shrink. The reason, however, is that the savings rate of Americans could rise further and the balance sheet recession continue. Traditionally currencies appreciate with higher savings (in local currency) and depreciate with more spending. - Click to enlarge

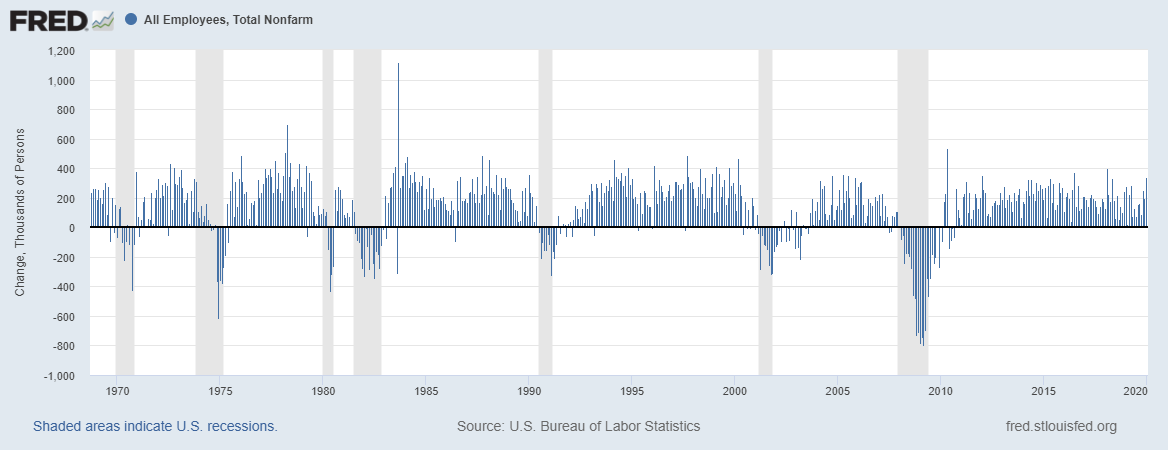

While manufacturing has recently returned to pre-recession levels of late 2007, energy production (included in mining) has soared as the energy industry has put fracking and new wells into production. B.C. Commented: “The remarkable untold story: Ex mining and oil and gas extraction, US Industrial Production has been in contraction for most of the period since Peak Oil in 2005-08.”The red line is the ratio of total production to mining/energy. Its decline reflects the dominance of mining/energy.

The remarkable untold story: Ex mining and oil and gas extraction, US Industrial Production has been in contraction for most of the period since Peak Oil in 2005-08.”

In July 2013, even before Mauldin was writing this dollar-bullish article and when the euro was about to fall under 1.30, we published: Why There Won’t Be A Strong Dollar, Even If The Financial Establishment Thinks So.

We continue to think that the relative American expansion, the strength of the dollar in 2013 and the weak oil price were mainly caused by austerity in Europe and more savings in Emerging Markets. This was accompanied by less savings in the United States, but not by a real change in competitiveness.

Those are driven mostly by wages, while technology is often quickly available everywhere in the world. As we pointed out in our article on the long-term wage developments, some emerging markets, in particular the Fragile Five, experienced too rapid wage increases.

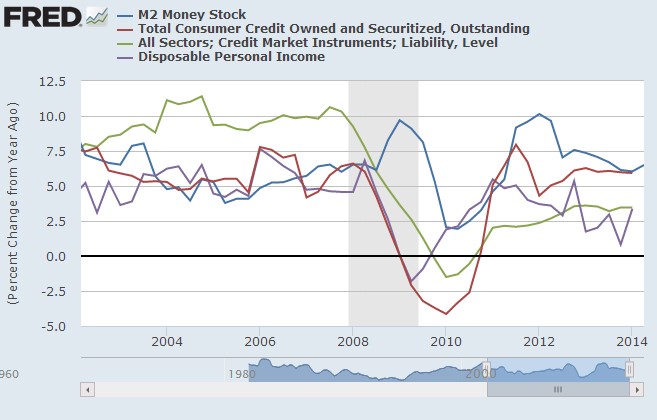

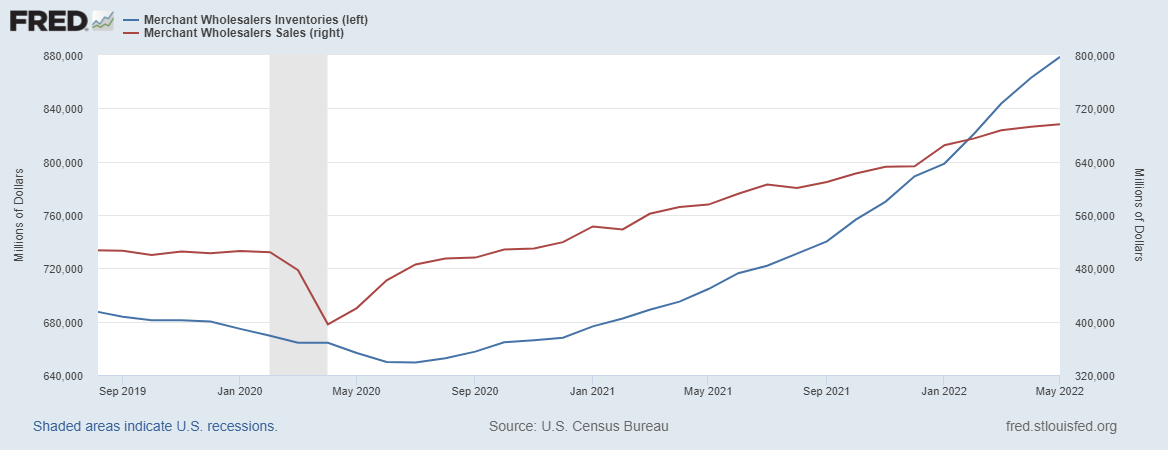

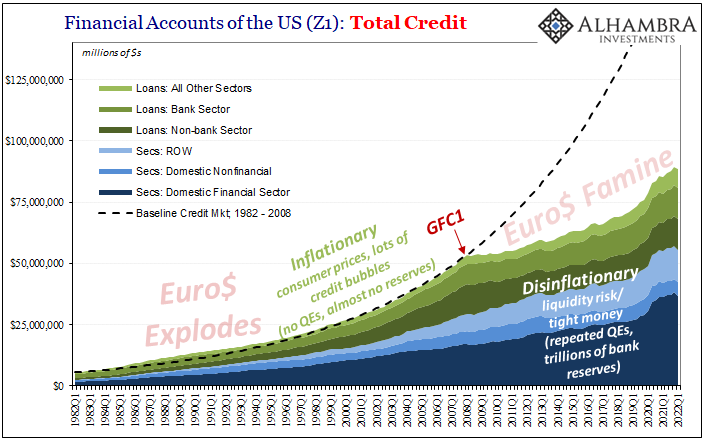

But we also indicated that the savings rate of Americans has risen to nearly 5% from 0.5% before the Great Stagnation. We continue to see weakness in U.S. spending. The following graph shows that until 2008 credit rose more quickly than money and income; Americans were spending beyond their means.

Since 2008 the picture has changed, credit and loans rise rise less than broad money supply or disposable income. That credit (the green or the red line) lies below the blue one or the pink one happened previously only during a recession.

Today banks are creating money in the U.S., even more than average of the last ten years and with that they provide liquidity to the world in addition to the U.S.trade deficit. A big part of these newly created dollars seem to flow as credit into high-yielding areas like the Emerging Markets. As emphasized in the article on wages, there are risks of too quickly rising spending, wages and credit in some Emerging Markets.

We judge that most Americans will continue to pay down their debt and maintain savings rates of 5% (a number still considerably lower than in Europe).

WolfStreet shows that according to the latest Gallup survery:

- Retirement savings: 18% spent more, 17% spent less.

- Leisure activities: 28% spent more, 31% spent less.

- Clothing: 25% spent more, 30% spent less.

- Consumer electronics: 20% spent more, 31% spent less.

- Travel: 26% spent more, 38% spent less.

- Dining out: 26% spent more, 38% spent less.

Only spending on essentials like food edged up. This new spending behaviour could reduce the U.S. trade deficit, and, combined with the lower unemployment rate, it represents the most efficient and sustainable way that the dollar can appreciate. On the other side, the combination of weak spending and a reduction of unemployment (aka wage expenses) is bearish for stocks. Given that the dollar often appreciates during phases of stronger equities, this represents a certain downside risk for the green-back.

But as the weak credit and spending figures show, the mainstream assumption that the Fed could hike rates, is definitely very far-fetched. At least this is good news for stock markets.

Read also:

Shale Oil and Oil Sands: Market Price Compared to Production Costs

Charles Hugh Smith: What’s Behind the Rise in U.S. Industrial Production?

BIS Working Paper: Global and euro imbalances: China and Germany

Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: credit,current account,M2,money,trade deficit,U.S. Consumer Spending,U.S. Industrial Production (ZH),U.S. Savings Rate,U.S. Trade Balance