We examine the relationship between strong dollar phases and austerity in other parts of the world. Between 1983 and 1985 one reason for the strong dollar were high real interest rates in the U.S. after the defeat of the Great Inflation period, the enforced austerity in Southern America and cheap commodity prices caused by generally low global growth. Between 1997 and 2002 the dollar was strong, because Germany had to finally digest the high costs of the reunification.

The vicious circle in Europe and the virtuous circle in the United States

The European and the U.S. economies have arrived in vicious and virtuous circles.

Vicious circle: German entrepreneurs do not spend when Chinese do not invest. Chinese do not invest when Europeans do austerity. Europeans must do more austerity if Germans do not spend.

Virtuous circle: American consumers spend when house prices rise and gas prices do not. Gas prices fall and US house prices rise when the rest of the world is in a vicious cycle and consumers spend.

However, the first vicious cycle can broken at several points:

- The PBoC could ease its currently very hawkish stand and Chinese invest more.

- German entrepreneurs could invest more, domestic orders are very weak compared to strong consumer sentiment. As opposed to Americans and many Southern Europeans, the Germans are not balance-sheet constrained, they have far lower private and public debt. About 36% of the Euro zone population (Germany, Austria, Belgium, Finland etc.) does not have this debt issue. On the contrary, these 36% received higher incomes in recent years.

- Europeans could do less austerity.

And the US virtuous cycle could be broken when US consumers do not really spend despite rising home prices, simply because many Americans have too much debt and want to pay down debt before they spend money.

Any break in the circles would mean that money shifts back from the U.S. into Europe or Emerging Markets and the dollar weakens again.

1998 to 2001: German and European austerity strengthens the dollar

The last time that a similar picture appeared, was in 1997/1998: Germany implemented harsh austerity after years of excessive spending following the reunification. Other European countries had already reduced spending and increased taxes to fulfill the Maastricht conditions.

| Year | German government gross debt | Percent Change |

|---|---|---|

| 1991 | 39.537 | |

| 1992 | 42.019 | 6.28 % |

| 1993 | 45.767 | 8.92 % |

| 1994 | 47.968 | 4.81 % |

| 1995 | 55.597 | 15.90 % |

| 1996 | 58.467 | 5.16 % |

| 1997 | 59.754 | 2.20 % |

| 1998 | 60.491 | 1.23 % |

| 1999 | 61.257 | 1.27 % |

| 2000 | 60.182 | -1.75 % |

| 2001 | 59.142 | -1.73 % |

| 2002 | 60.748 | 2.72 % |

| 2003 | 64.426 | 6.05 % |

| 2004 | 66.204 | 2.76 % |

| 2005 | 68.514 | 3.49 % (source) |

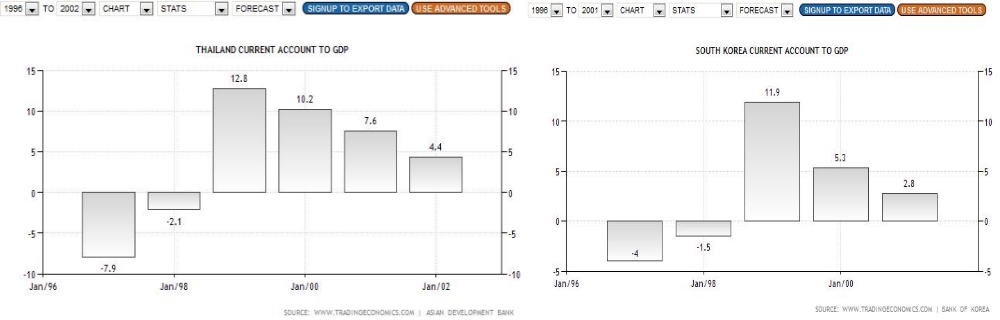

In 1998, the Asia crisis put more fuel into the fire: Less Asian demand weakened Europe.

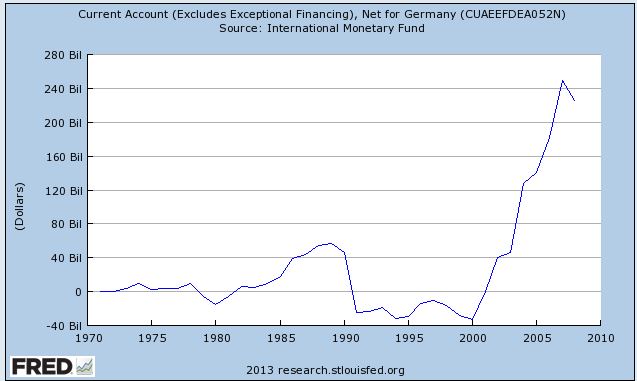

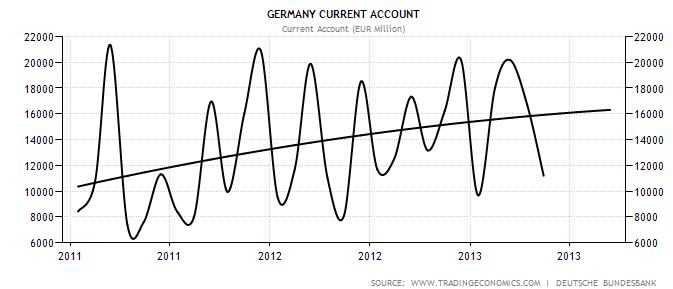

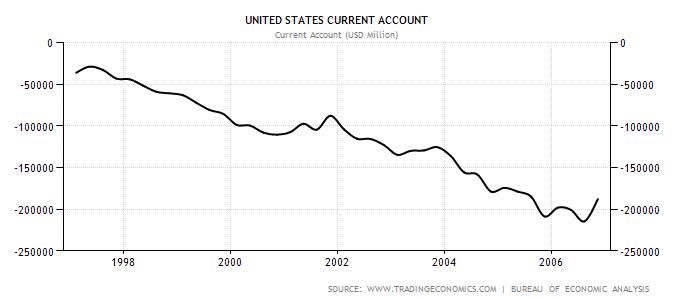

A decade of weak German spending, private debt reduction and huge current account surpluses followed.

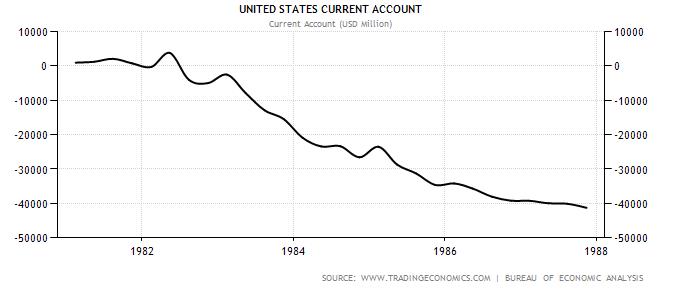

The U.S. was spending, until these excesses exploded in the financial crisis.

In the first phase of the rising deficits, the euro fell from 1.20 to 0.85 US dollars in 2001, until the Fed lowered rates despite high deficits.

In the first phase of the rising deficits, the euro fell from 1.20 to 0.85 US dollars in 2001, until the Fed lowered rates despite high deficits.

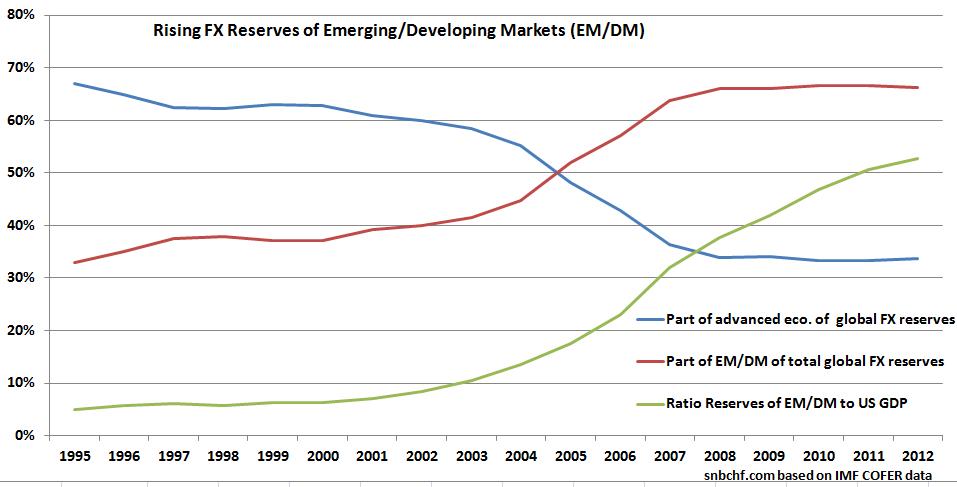

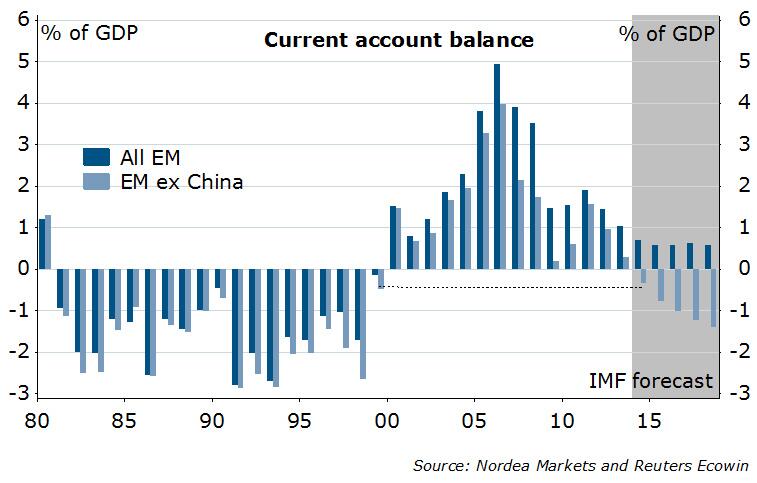

From 2001, emerging markets were progressing and increasing their wealth, FX reserves of emerging and developing nations rose from 5% to 50% of US GDP. The success of emerging markets drove commodity prices up and the dollar fell even more.

Since 2011: European austerity strengthens the dollar

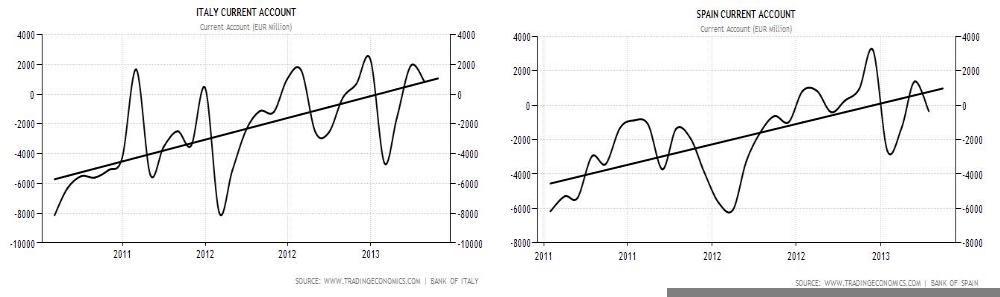

Since 2011, European leaders have explicitly targeted current account surpluses, e.g. visible in the Spanish bailout statement.

A shift to durable current account surpluses will be required to reduce external debt to a sustainable level. (source Spanish bailout June 2012)

European leaders followed the Austrian economist principle established by Böhm-Bawerk:

It follows: “The capital account rules the trade balance/current account. Who wants to avoid deficits in the trade balance must tackle the economic variables on the capital account (increase savings, increase investments, reduce budgets and (yes!) tighten monetary policy) (based on Böhm-Bawerk)

Austerity and weak growth let the euro fall from 1.45 in 2011 to 1.27 recently, but current account surpluses have been achieved and are increasing.

Now that the aim of achieving current account surpluses has taken effect, ECB’s Benoît Cœuré is asking if a lost decade is looming .

The specific risk scenario that I wish to consider is that of a “lost decade” ‑ the possibility of a much more protracted period of stagnation than currently anticipated.

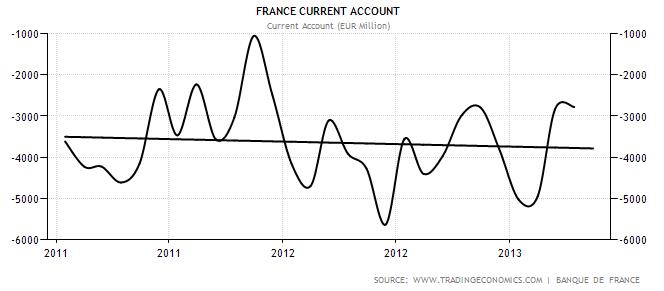

Admittedly, France has started very late with the deficit reduction:

And Germany demonstrates its solidarity, even if it does not need to do austerity:

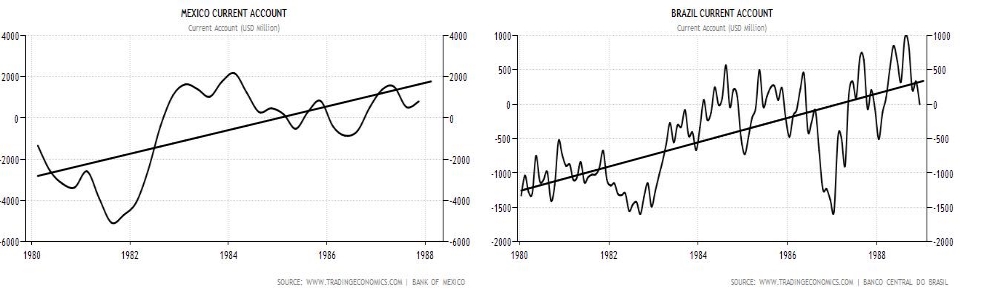

1982-1987: South American austerity and oil glut strengthens the dollar

The Washington consensus similarly obliged Latin Americans to implement austerity: The combination of austerity and cheap commodity prices resulted in a lost decade. The U.S., however, profited from the oil glut and weak global growth.

Despite cheap oil prices the U.S. was spending and increasing current account deficits. The dollar reached a top in 1985, when central banks stopped the dollar strength with the Plaza Accord.

The questions remains: Who is spending this time?

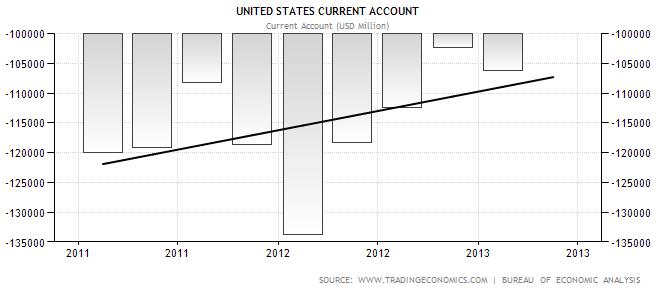

When Europeans are doing austerity, does the United States spend? No!

Americans might still be lost in their balance sheet recession: despite recent higher spending, debt reduction might be more important. GDP is rising very slowly, U.S. salaries do not really increase.

Who will be spending, this time?

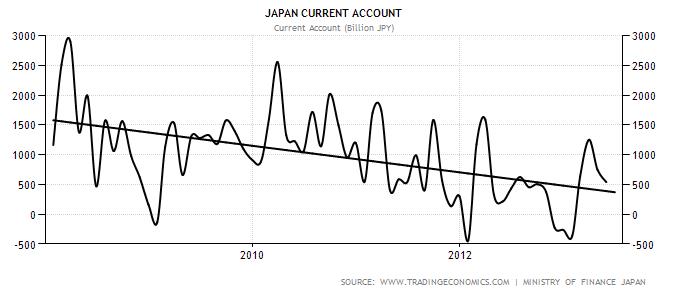

The answers might be here: Emerging Markets and Japan.

Summary

Between 1983 and 1985, one reason was the high real interest rates in the U.S. after the defeat of the Great Inflation period, the enforced austerity in South America and cheap commodity prices caused by generally low global growth.

Between 1997 and 2002 the dollar was strong, because Germany had to finally digest the high costs of the reunification. Eastern Germany was still missing competitiveness, unemployment was high. The rest of Europe implemented austerity to get ready for the euro and France and Italy achieved trade surpluses. These surpluses flooded into the United States to benefit from the dot com bubble and strengthened the dollar.

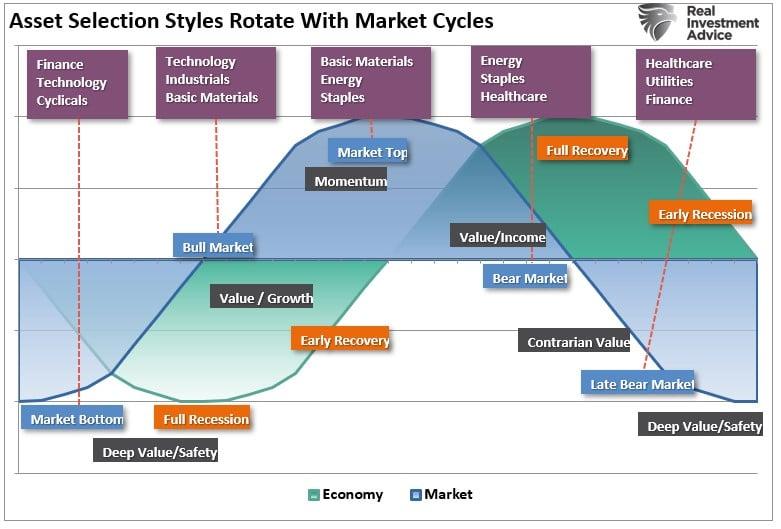

Austerity and slow growth in Europe could enable a period of a stronger dollar. In a second part of this essay, we will compare the ISM index for manufacturing and interest rate differential for the different periods.

Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: austerity,current account,Japan,Japan Current Account,Latin America,lost decade