Introduction via cointelegraph.com

Cracks in the financial system and currency pegging

If a country is able to control its domestic currency it can and will in effect keep its exchange rate low. This helps support the competitiveness of the country’s exports sold abroad. These low exchange rates help boost profitability from domestic companies selling goods internationally by keeping the costs of production low and selling to countries with stronger currencies (think China, the U.S. and Eurozone).

By pegging your currency, you are ensuring that your currency can’t strengthen to a point where it hurts the domestic economy and placing a tight band so as to smooth out volatile currency swings and reduce the likelihood of a currency crisis. If your currency experiences a sharp appreciation, it makes your products and services more expensive and less competitive in the market, which is recessionary.

However, this does come with a cost. When a country fixes (pegs) its exchange rate, it must be maintained within the band that is set. This requires a large amount of reserves because the country’s government and central bank have to constantly buy and sell its domestic currency. The problem with this is it can have really bad inflationary side effects. In order to maintain this reserve a country has to increase its money supply, since you need to hold more currency reserves in order to take action as necessary.

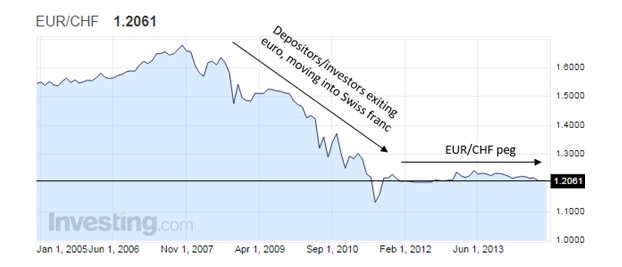

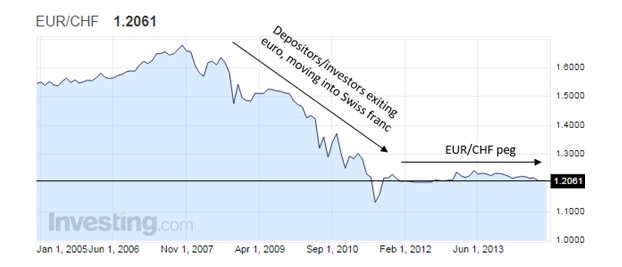

This will cause rising domestic prices and increase domestic instability, which is the exact opposite of what a currency peg is designed to do i.e to support a rising standard of living for the population and protect the domestic economy from price spikes. Below is an example of what the peg looks like.

The Swiss decided to peg their currency to the Euro because the Swiss Franc is seen as a flight to safety and as a safe proxy to global growth.

The logical sequence is:

- The central bank prints money and artificially makes local assets cheaper for foreigners

- Asset prices in the local economy go up

- Real estate prices move into higher rents

- Higher rents and higher asset prices translate into higher living costs

- Wage earners want to be compensated for higher living costs

- Wages go up –> wage inflation

- Entrepreneurs raise prices so that margins are maintained

- Result is price inflation or potentially a wage-price-spiral

The “Save Our Swiss Gold” backdrop has arisen out of a failed policy of currency pegging.

Important!

Our Core Thesis: European leaders have successfully implemented austerity, disallowed notorious wage increases in the periphery and nearly introduced deflation. Inflation differences between the euro zone and Switzerland will decrease to zero, Swiss CPI inflation might even be higher in some years. The CHF real eff. FX rate overvaluation talk disregards completely the continuous immigration into Switzerland. Therefore EUR/CHF will remain close to 1.20. Risk-off flows will not leave Switzerland, but they will be converted into risk-on flows (stocks and real estate) thanks to immigration, higher Swiss GDP growth and relatively weak Swiss wage hikes. In particular, in the housing sector these flows will build up wrong resource allocations. In some years stronger global growth and high German wage increases will boost inflation in Germany and partially in Switzerland but Southern Europe will still struggle. By tradition, Germans will move funds into Switzerland in order to protect them from inflation and the ECB. At that moment the SNB will need to hike interest rates - possibly before the ECB. The Swiss "Soros moment" will arrive and the EUR/CHF will fall under 1.20.

The consequence for monetary policy will be:

- Either the SNB fights inflation and the Swiss real estate bubble, and allows a CHF appreciation. This implies selling FX reserves below the price of EUR/CHF 1.20 and/or accumulating more and more reserves.

- Switzerland accepts higher inflation and consequently gives up its competitive advantage in lower inflation and lower borrowing rates. The latter scenario was excluded by the SNB's Thomas Jordan already in 1999 when he pledged against a euro membership. The SNB mandate explicitly disallows inflation.

The first scenario, that the EUR/CHF falls under 1.20 is the only feasible solution. Whether the SNB suffers a big loss depends on the

income on seigniorage it can generate as opposed to FX rate losses. Hence SNB's monetary policy will switch to a

managed currency appreciation like

the Singapore or Chinese central banks already do for years.

In

regular posts we show how the Swiss CPI comes closer and closer to euro zone inflation. One day, maybe in 10 or 20 years, the Swiss franc will depreciate more strongly, but this will be only after the bust of the Swiss real estate bubble.

George Dorgan (penname) predicted the end of the EUR/CHF peg at the CFA Society and at many occasions on SeekingAlpha.com and on this blog. Several Swiss and international financial advisors support the site. These firms aim to deliver independent advice from the often misleading mainstream of banks and asset managers.

George is FinTech entrepreneur, financial author and alternative economist. He speak seven languages fluently.

See more for About

6 comments

Skip to comment form ↓

Stefan Wiesendanger

2014-06-21 at 17:01 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

The above Core Thesis is a very fitting analysis and a likely prediction as far as a continuing long-term upward trend of the CHF is concerned. I am less convinced however the Switzerland will not accept higher inflation as a way out since the SNB has already shown itself to be pragmatic in the face of extraordinary circumstances and when backed by the political and economic establishment.

The all-important question is what kind of inflation it is going to be. Wage-driven inflation might look like an acceptable solution in the future while the credit-fueled variant will not (and is not necessary given the strength of the Swiss economy) and is therefore actively combated by the SNB.

Let’s look at the very similar situation of Germany first. Both the SNB and the Bundesbank have years of cumulative current-account surpluses on their balance sheets, in the German case as a TARGET-2 balance and in the case of the SNB as foreign-exchange reserves. The surpluses ended up there when, during the financial crisis, the banks started to deleverage and companies repatriated cash from their peripheral operations to the safety of their homeland (private capital flight played a negligible role in comparison if it happened at all). The only difference between the two countries is that Switzerland decided not to let the CHF appreciate while Germany as part of the Euro system had no such choice. How is Germany going to adapt? Through wage increases and a rather ill-designed increase of pension benefits (ill-designed because it limits active years instead of increasing them – benefits had better be increased in monetary terms). How will Switzerland adapt? Wage increases would in my opinion not be the worst option.

This path has implicitly been chosen by the people in the recent vote on tightening of immigration. Consumer-price inflation will in this case be concentrated in the non-tradeables because tradeables move rather freely in the Single Market of which Switzerland is a member for all practical purposes.

Wage-driven inflation will also benefit the active generations vs. savers and retirees which does not seem unfair given the subsidizing of retirees in the current pension system with its too high pension payments. The SNB would obviously be pleased with this outcome because it is easier to sell missing the inflation target rather than announcing the destruction of its equity. But the SNB cannot force the private sector to increase wages – only labor scarcity and public employers can.

Will this be enough? Probably not and the SNB will have to book some foreign-exchange losses. Whatever the final policy mix will turn out to be, I would not be surprised to see wage increases as an important element. What does this all mean for the export sector? Whatever the mix of welcome wage inflation, not so welcome credit-fueled inflation and currency appreciation will be, the input costs of the export sector will go up. After this sector has been bailed out by the SNB and now has enjoyed a few years protected from reality, it is now time for the export sector to pay back the SNB by readying itself for the coming, inevitable adaptation: by investing in productivity, cutting cost and focusing on the highest-margin products. Unfortunately, the CHF floor forces the SNB to communicate that the CHF is over-valued, a message readily echoed by the media. The very real danger is that the export sector believes this out of convenience instead of working on their fitness now more than ever. As an afterthought: A further, mitigating policy option to take pressure off the SNB would be any policy that makes investing abroad easier. First on my mind are investment restrictions on pension funds.

George Dorgan

2014-06-22 at 08:31 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

No, wage-driven inflation is no solution. As I explained here , Switzerland might repeat the 1990s pattern. High German spending and inflation after the reunification plus the SIC introduction created an massive expansion of Swiss money supply, it incited Swiss investments to export to the now bigger Germany. This money supply went quickly into higher wages and price inflation. Some years later, the SNB hiked rates to prevent a continuing price inflation. With that, however, the SNB wrecked the Swiss real estate market. But it had no chance, it was too late.

Due to the big debt levels and the variable rate 2nd mortgages, Swiss home prices are very sensitive to rate changes.

Applying these arguments, it is now time to hike Swiss interest rates, in order to prevent a massive hike later.

Stefan Wiesendanger

2014-06-22 at 18:28 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

I am nowhere near competent enough to give any kind of recommendation. As a personal opinion however, I agree with your statement that hiking interest rates now would be the best option. With my earlier comment, I meant to draw attention to the possibilities for the real economy to bear part of the adaptation load, and by which measures. A rising wage level would not appear negatively in this context. Also, I wanted to highlight the danger for industry to believe the media talk that the CHF is overvalued, a message that is serving another agenda than the well-being of industry.

George Dorgan

2014-06-27 at 05:32 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

The focus on (price) inflation that is at 0.2% only, plus the slight cooling on the real estate market, caused by European disinflation, provide arguments enough not to hike rates now and possibly not in the next 2 or 3 years. The CHF overvaluation show helps. But I do not believe that wages will really increase more than 1% per year. In many areas like in banks or multi-nationals there is always the “outsourcing” thread. We gotta wait at least 5 years for wages rising by 2% p.a., like they do in Germany or the U.S.

Interestingly the argument about the variable 2nd mortgage has been addressed just now. Swiss must pay back 2/3 of their housing debt after 15 instead of 20 years before.

TolerantLiberty

2014-09-18 at 14:19 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

JP Morgan’s comment on the Monetary meeing September 2014:

It remains to be seen whether the SNB will cut the deposit rate as early as the quarterly meeting on September 18th. The dilemma for the SNB, which presumably why it has not acted on interest rates since before the floor was introduced, is that a further easing is interest rates is not necessarily appropriate for the Swiss economy, not least as this would run counter to the SNB’s efforts to ensure financial stability through a slowing in credit growth and house prices. Failure to cut this week would probably ensure an outright test of 1.20, so the stakes are high. Should the SNB cut we would raise our forecasts for EUR/CHF for a couple of quarters, albeit still retain a longer-term downward trajectory for the cross. The Swiss economy is fundamentally healthier and less deflation-prone than the Euro area, so it is not obvious to us that the SNB will be in a position to match ECB easing for as long as is necessary for the ECB to reflate the Euro area.

OliverCorneau

2014-10-29 at 10:24 (UTC 2) Link to this comment

History of Swiss sound gold backed franc:

http://web.archive.org/web/20141216132833/http://www.mauldineconomics.com/ttmygh/this-little-piggy-bent-the-market