For the last five years Larry Summers has called it secular stagnation. It’s the right general idea as far as the result, if totally wrong as to its cause. Alvin Hansen, who first coined the term and thought up the thesis in the thirties, was thoroughly disproved by the fifties. Some, perhaps many Economists today believe it was WWII which actually did the disproving.

For many of them, it is the typical broken windows stuff. The war devastated Europe and much of the Far East, therefore it required a whole bunch of purportedly economy-enhancing rebuilding spread out over many years. Making the best of a terrible situation via John Maynard Keynes.

Others say it wasn’t so much the rebuilding itself as it was the technological innovations that the war brought up.

There is no doubt that our modern interconnected world owes much to the new ideas and new thinking that arose out of the necessity to beat the Axis powers.

To this second group of Economists, perhaps that accounts for the defeat secular stagnation as well as the Nazis. In the latter decades of the 20th century and the first two of the 21st, though, the lack of “enough” war might account for a very determined change in growth.

Having lived for so long under relative peace and harmony, they claim we’ve all lost our edge. Without the base instincts for survival that war brings on, maybe that explains the languishing (though no one will answer why this all would’ve mattered so much starting in, I don’t know, 2008).

If you think I’m making this up (I realize that it sounds like I am), let me quote Economist Tyler Cowen in 2014 groping for answers as to the world economy’s persistent malaise (partial credit for realizing how it was a malaise):

Counterintuitive though it may sound, the greater peacefulness of the world may make the attainment of higher rates of economic growth less urgent and thus less likely. This view does not claim that fighting wars improves economies, as of course the actual conflict brings death and destruction. The claim is also distinct from the Keynesian argument that preparing for war lifts government spending and puts people to work. Rather, the very possibility of war focuses the attention of governments on getting some basic decisions right — whether investing in science or simply liberalizing the economy. Such focus ends up improving a nation’s longer-run prospects.

We apparently need the threat of mass casualties to goose R* back up away from zero. A whole lot more down and dirty war to get the creative juices, and the economy, up and running at full speed again? No thanks.

Besides, the view is entirely backward. History shows pretty conclusively that the big conflicts typically follow the big economic setbacks. The economy stops working (which used to mean the people stopped being able to eat) and leadership seeks out a “common enemy” by which to refocus the anger. Been a bit of that already around the world, if still small-scale.

If there’s been a peaceful break in terms of great conflicts, and there surely has, it has had as much to with the positive aspects of eurodollar globalization these last fifty years. Without eurodollar growth, there is no more positive spin from globalization. The world is left instead to deal with this “secular stagnation” without any frame of reference to understand it or the very negative global effects.

As a result, Dr. Cowen may yet see his theory put to the test.

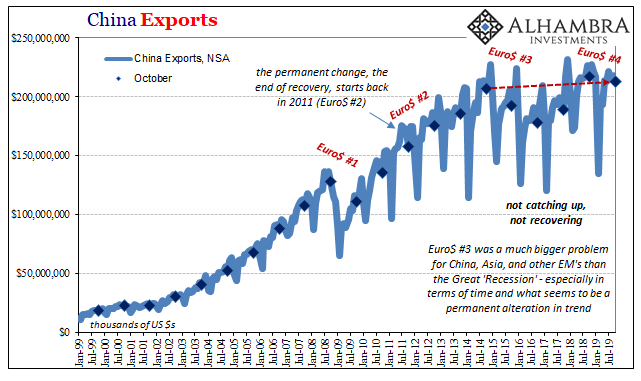

Joseph Wu, that foreign minister, walked his comments back just a little. He was speaking more of the future than the present, he said. Wu characterized China’s current situation as, “OK.” Is it, though? Using the latest data for China and global trade, what you find is that China is quite a long way away from OK. And by extension, everyone else around the world who required globalization running through China for stability in their home countries. The Chinese General Customs Administration reported last night that exports leaving the country were 0.3% less in October 2019 than they had been in October 2018. Like US payrolls or the ridiculous view on the ISM’s Non-manufacturing PMI, that small minus has been talked about like it’s some sort of strong number. Strong as in, at least it wasn’t worse. Never mind that it’s already a minus when China needs 20-30% growth, the number by itself also understates the magnitude of the problem right now. What I mean by that is how the global economy deprived of global trade hasn’t ever recovered from Euro$ #3 – let alone Euro$ #1. |

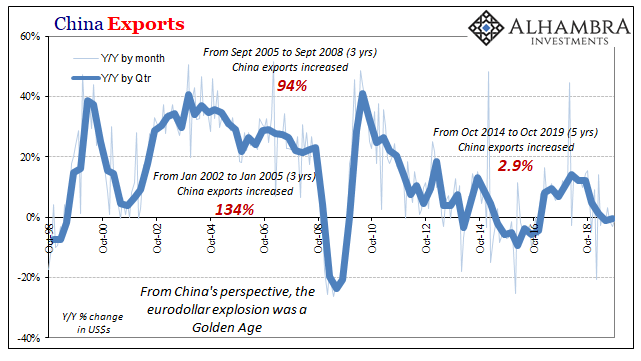

China Exports, 1998-2019(see more posts on China Exports, ) |

| The numbers are simply staggering – when you look at them in any sort of context. Between January 2002 and January 2005, a golden miracle era period which set the world’s economic expectations for the future, Chinese exports more than doubled. In three years!

And then doubled again in another three. Now look at the last five. Between October 2014 and October 2019, Chinese exports have increased by less than 3%; not per year, total. Which means they haven’t grown at all in half a decade. Therefore, the -0.3% year-over-year number for October 2019 minimizes just how far behind the Chinese are lagging, leaving the rest of the world in the same predicament. A minus for exports is bad; minus plus no recovery equals Joseph Wu. The more small minuses at this stage don’t just demonstrate how there is no growth now, more importantly they say there can’t be any growth the way things are. There’s a whole lot more in that -0.3% than meets the eye. |

China Exports, 1999-2019(see more posts on China Exports, ) |

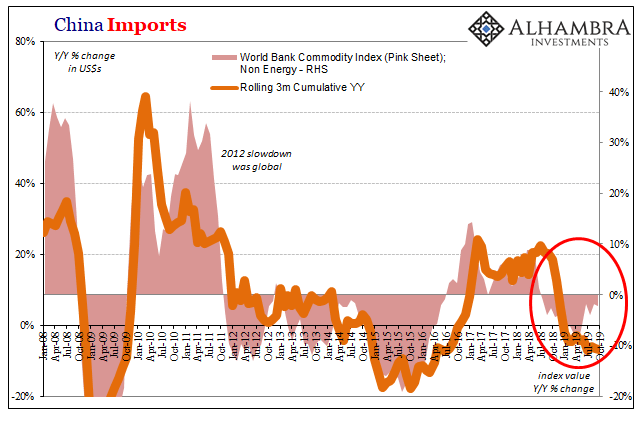

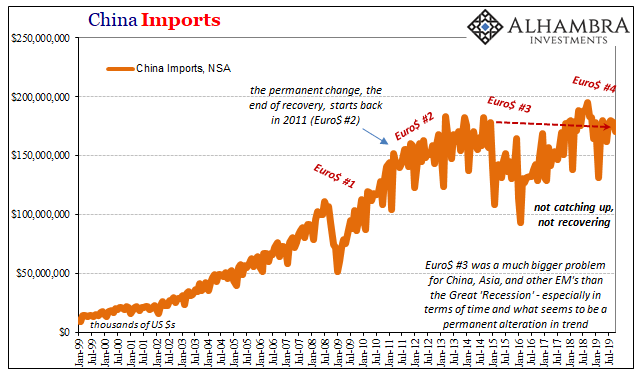

| The Chinese, of course, tried to manage this external economic problem (as well as the effects of the monetary system cause) without any success. For the internal asset bubbles and outward slogans of “rebalancing”, China’s imports look exactly like China’s exports.

No growth whatsoever for now five years and counting. It is simply mind-boggling how little appreciation there is for this deficit (largely because we are told to focus only on the annual comparisons, which is why 2017 was so overhyped beyond any reasonable basis and context). |

China Imports, 2008-2019(see more posts on China Imports, ) |

| As to the latest annual figures, imports into China dropped by 6.4% year-over-year last month. And like exports, that number way understates the figurative level of economic pain not just inside this one country but for all countries particularly those which are absolutely counting on the Chinese economy for their own prospects for expansion. |

China Imports, 1999-2019(see more posts on China Imports, ) |

It’s just another reminder of what globally synchronized growth really was (a bumper sticker slogan) as well as what it was not (actual growth). Which further calls into question all those officials (central bankers) who based their entire outlook upon it (the same who somehow continue to say the economy is still pretty strong).

And they’ll also be the first to tell you there’s no danger here, even though we can all see it creeping into almost everything everywhere.

It may just be bluster from the Taiwanese; after all, they’ve been worried about and talking about a Chinese invasion ever since Chiang Kai Shek fled to the island to escape Mao’s Communist forces establishing the People’s Republic of China in 1949.

Then again, what’s truly different this time as opposed to the last forty years is the internal situation inside the PRC. A country deprived of economic growth is a dangerous country; a wounded animal backed into a corner fighting for its survival.

Apologies to Tyler Cowen, the threat of more war isn’t going to get us all out of this stagnation. What will is some actual honesty about the economy, if Economists have it in them (which I very much doubt). The real potential for a boom might not be in the economy.

The post The Real Boom Potential appeared first on Alhambra Investments.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: China,China Exports,China Imports,economy,EuroDollar,exports,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,global trade,imports,Larry Summers,newsletter,secular stagnation,Taiwan