Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, recently declared: “I do not believe there’s an AI bubble by any imagination.” We agree and disagree. We believe AI is a technological game-changer on par with the invention of the computer and the internet. AI technology is not a bubble and will prove incredibly valuable and productive. However, it's quite likely that many AI investments are in the midst of a financial bubble.

Our concern about an AI financial bubble is grounded in the work of innovation economist Carlota Perez and her acclaimed book, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital: The Dynamics of Bubbles and Golden Ages. Although written in 2002, well before the AI boom, her book offers a clear explanation of why speculative financial bubbles often accompany significant technological innovations. Accordingly, we extrapolate her thoughts and apply them to the AI boom.

Before proceeding, we think it's appropriate to add context to Larry Fink’s beliefs with a quote from Upton Sinclair:

It is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.

Innovation Does Not Guarantee Returns

Carlota Perez believes that the mere existence of a revolutionary technology that benefits the economy, increases corporate profits, and makes society wealthier doesn’t guarantee sustained investor profits. This is especially true when stock prices race ahead of new technological benefits and price in tomorrow's idealized future outcomes today.

Investors, especially those who invest early in a new technology, often conflate technological progress with capital deployment. History shows that substantial capital is lost in the early stages of investment, even with revolutionary innovations. For example:

- The railroads were transformational for commerce and the physical and economic expansion of the US, but many railroad stocks went bust.

- Electricity revolutionized the economy, yet many of the first electrical firms failed.

- More recently, the internet transformed communication and commerce. The internet-heavy Nasdaq lost nearly 80% after its bubble burst in 2000, and many of its early leaders no longer exist, despite its transformative role in the economy.

“Technological revolutions do not necessarily bring immediate profits to investors; on the contrary, they often involve massive destruction of capital.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

Financial Capital Runs Ahead of Economic Reality

Perez makes an important distinction between technological capital, which evolves slowly, and financial capital, which is impatient and very susceptible to faulty narratives.

Technological capital consists of machines, processes, know-how, networks, and skills. This form of capital accumulates slowly as innovation occurs.

Financial capital is impatient and doesn’t want to wait decades for the financial benefits of new technology. Instead, investors price in long-term possibilities as if they are near-term certainties. Perez explains that the speculative phase of a technological revolution is dominated by grand expectations, leverage, and storytelling.

We observe such narratives in AI-related companies today. For example, investors are pricing some AI stocks as if:

- Monetization is inevitable and imminent

- Today’s first movers will be the long-term winners

- Adoption will be quick, smooth, and universal

- Margins will remain permanently elevated

- Competition will be limited

As we have learned with prior technological advances, none of those assumptions are assured or, in some cases, realistic.

“Financial capital is by nature footloose, impatient, and speculative, while production capital is tied to the long-term accumulation of capabilities.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

Narratives Trump Traditional Valuation Techniques

One commonality observed at the start of technological change is the dismissal of traditional valuation metrics. Investors are told that earnings don’t matter. In the case of AI, we are told that metrics such as capital expenditures, current margins, and market dominance should be used to value companies.

The same persuasive arguments sound eerily like those heard in prior booms:

- Dot-com bubble: companies were valued not on profits but on “eyeballs.”

- Housing bubble: home prices could “never fall nationally.”

- SPAC boom: profit projections replaced profits

- Pandemic “Stay at Home” bubble: investors presumed the boost in demand was a permanent structural economic shift.

Consider the following paragraph about the British railway mania in the 1800s from Reuters:

In “Engines that Move Markets: Technology Investing from Railroads to the Internet and Beyond”, Alasdair Nairn writes that tech bubbles are characterised by the emergence of a technology about which extravagant claims can be made with apparent justification. New publications uncritically promote the invention. Entrepreneurs create new companies to meet demand from investors, who suspend normal valuation criteria. The technology is often immature. There follows a huge over-commitment of capital, forcing down potential rates of return.

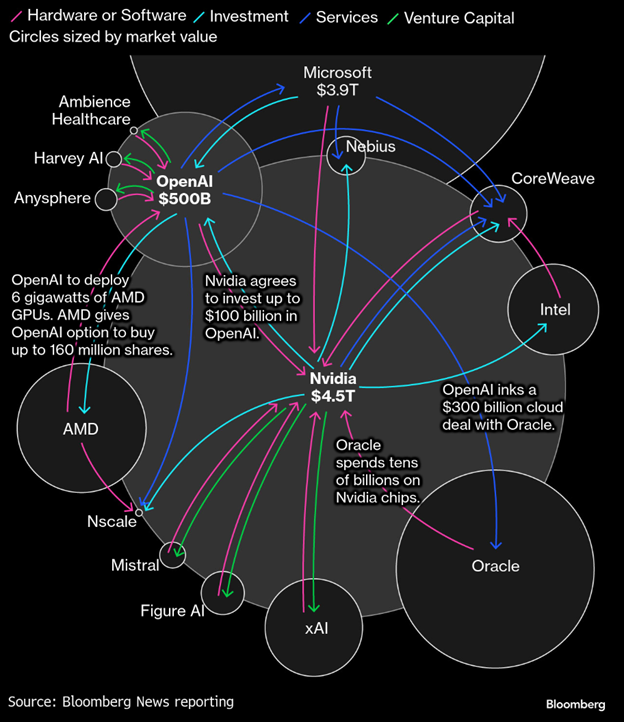

Today, a company’s involvement with AI, no matter how profitable it is or will be, has become a justification to ignore fundamentals. We have witnessed stock prices rise substantially solely because corporate executives reference AI on earnings calls. For some investors, capital expenditures for AI-related projects are equated with a guarantee of future profits. In fact, for the most part, investors seem to believe that the greater the capital spend, the greater the likelihood of success. Today’s circular financing arrangements, as shown below courtesy of Bloomberg, are applauded despite their questionable foundation.

Perez would describe this optimistic phase as the period during which financial capital detaches from the technology.

It is worth noting that, unlike the dotcom bubble, some of the largest AI companies, such as Nvidia, Google, Microsoft, and Meta, have significant revenue and earnings growth. However, many other smaller companies, public and private, fit Perez’s bill, trading on the promise of future growth.

“In the frenzy phase, financial capital decouples from production capital and moves in a self-referential way, guided by expectations of capital gains rather than by real profitability.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

Infrastructure Lags Innovation

Another lesson from Perez’s work is that capital expenditures and infrastructure buildouts lag innovation by years or even decades. For example, AI will be used by billions of people worldwide and play a role in almost all businesses. However, the ultimate benefits for most end users will not likely be realized until well after the investments have been made.

For example, the full benefits of computers were not realized until software development caught up. The internet required a series of massive investments before becoming commercially viable. AI is no different.

That gap between market expectations and economic reality is where bubbles form.

“The full benefits of each technological revolution are only realized long after the installation of the new infrastructure has been completed.” — Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

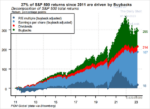

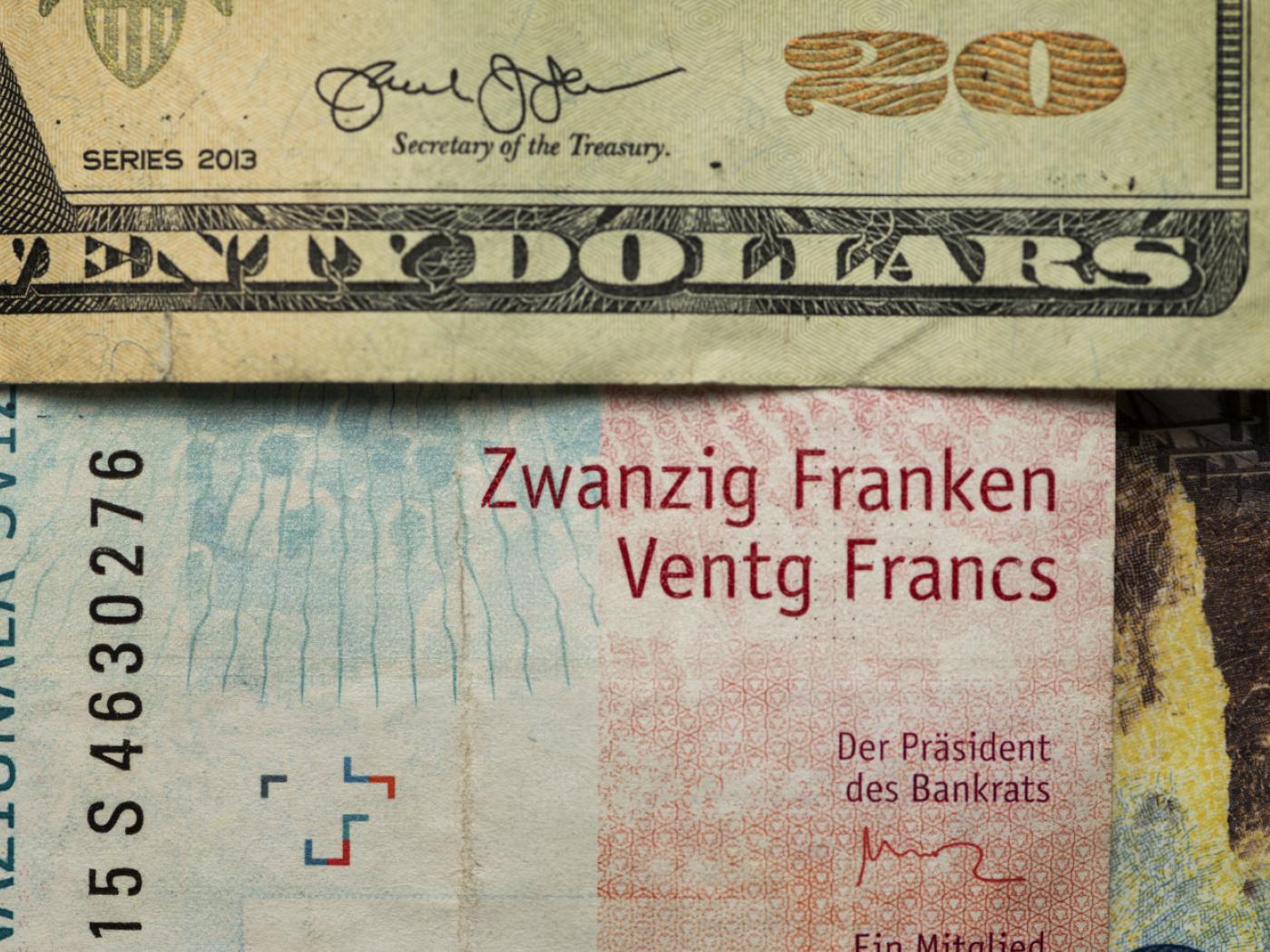

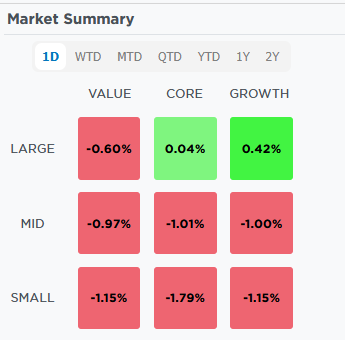

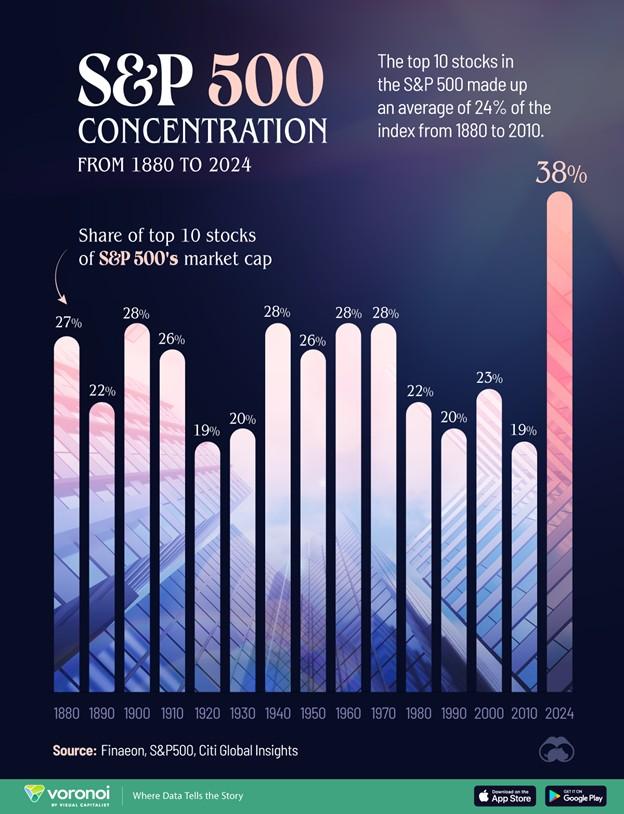

Market Concentration

Speculative bubbles are also characterized by market concentration. Capital flows disproportionately into a small number of perceived winners. As market breadth narrows, index performance becomes more dependent on a handful of stocks.

This has been incredibly obvious over the last few years, as shown below courtesy of Visual Capitalist. A small number of mega-cap companies, including many of the Magnificent Seven, dominate AI-related investment narratives, index returns, and capital flows. Investors assume these firms will capture most of the future profits simply because they are early leaders.

History suggests that first movers often overinvest and oftentimes fail. They inevitably face rising competition and contracting margins. Later entrants frequently benefit from lower costs and better business models. Moreover, this future competition spends more efficiently, as they have greater insight into what the ultimate technology will look like. For instance, according to ChatGPT, these were the top 7 search engines in 1999:

- Yahoo

- AltaVista

- Lycos

- Excite

- MSN Search

- Ask Jeeves

- AOL

Google didn’t make the list. Today, Google accounts for approximately 90% of global searches. Equally telling, we use the word “Google” as a synonym for internet searches. Of the list above, Yahoo currently has the highest search engine market share, at an estimated 1.2-1.4%.

“During the speculative frenzy, financial capital tends to concentrate on a few apparent winners, creating the illusion of permanence long before the competitive landscape has stabilized.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

The Inevitable Reckoning

Speculative bubbles pop not because technology fails, but because capital becomes scarce, profitability disappoints, narratives fail to reflect reality, and, at times, government policies shift.

Importantly, this process does not destroy the technology. It restores discipline to capital markets. This discipline allows capital to flow to the most productive and innovative companies, thereby improving technology.

Perez argues that the most productive phase of a technological revolution occurs after the bubble bursts, when excess capacity exists, costs fall, and adoption becomes widespread.

“The collapse of the bubble marks the turning point that allows the full deployment of the technological revolution to begin.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

The Real Opportunity Comes Later

Investors often assume that avoiding bubbles entails foregoing opportunities to profit from innovation. According to Perez, history doesn’t agree. The best long-term returns typically occur after expectations reset, not when enthusiasm peaks.

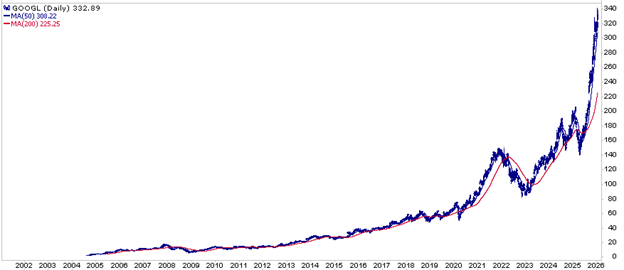

For instance, as noted above, Yahoo was the leading search engine in 1999. At the time, the stock was up substantially, clearly pricing in a bright future as “THE” search engine for years, maybe decades, to come. Many of those investors lost dearly, as shown below.

Conversely, Google wasn’t on many investors' radars as its search engine was largely unknown. Patient investors who watched from the sidelines as the dotcom bubble expanded and then burst could have bought Google at a split-adjusted price of $2.61 in 2004. Today, it trades at $330, yielding an annualized 26% return over the past 21 years.

“The biggest and most sustainable profits tend to be made after the bubble has collapsed, not during the speculative frenzy.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

Summary

“The speculative bubble is not an accident or a deviation, but a necessary phase in the installation of a new technological paradigm.”

— Carlota Perez, Technological Revolutions and Financial Capital

In our view, the key takeaway from Perez’s work is that investors are impatient. They believe they know with certainty what the future holds, thus justifying the current price reflecting discounted pie-in-the-sky cash flow forecasts. No one knows what the future holds, especially not with burgeoning technologies such as AI. This period we are in today, before the future unfolds, rewards pundits toting very convincing false narratives.

AI is not immune to the speculative cycle Perez lays out in her book. The technology is real, but the investment opportunity is far from understood. Appreciating the stark difference between these two states is essential for risk management. As Perez highlights, the best opportunities in AI may not be in today’s high-fliers but in lesser-known companies, some of which may still be private or not yet formed.

Paying too much for a great idea can yield the same result as buying a bad one.

The post AI Bubble: History Says Caution Is Warranted appeared first on RIA.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Featured,newsletter