Over the last couple of years, inflation alarmists such as Paul Tudor Jones, James Grant, and Jeff Gundlach have all said that inflation is returning with force. In different ways, they each stated that they would not own Treasury bonds due to the expectation that inflation would rise as the dollar declined due to the ongoing deficits. They have all argued, in some form or another, that ballooning deficits, tariffs, and the "dollar debasement" would drive inflation much higher, with yields of 6% or more on the 10-year Treasury as inevitable.

As Jeff Gundlach noted in June of this year, a "reckoning is coming" for U.S. debt, and yields on long-term bonds could continue to rise as the economy weakens. Paul Tudor Jones said in October 2024 that "all roads lead to inflation." Lastly, in June 2024, James Grant stated that "persistent inflation" is the new norm.

However, while these are brilliant, well-regarded gentlemen, the forecasts have not panned out, at least so far, as they believed, because they ignored the structural weight of the "3-Ds" (Debt, Deficits, and Demographics) on economic growth, which drives inflation.

Of course, it hasn't been just these three gentlemen discussing higher inflation and higher interest rates. Inflation alarmists have filled media headlines over the last few years, making a myriad of claims, but they have misunderstood what drives inflation in a consumer-driven economy. Furthermore, they misjudged the nature of money creation in a debt-saturated system.

Veil Of Money

Let's start by understanding the basics of money supply. The media often states that the Government is "printing money," which will lead to inflation. The reasoning is sound on the surface; if a government prints more dollars, each of those dollars has less value, in theory. However, that view misses two crucial points. First, as discussed in "Money Printing," the government does not "print money."

"Modern economies operate under an endogenous money system, meaning banks create money in response to economic activity. As the Bank of England explained in its 2014 paper “Money creation in the modern economy,” it is not central banks that directly dictate broad money growth, but rather commercial banks extending credit when they see viable opportunities. Put simply: loans create deposits."

Re-read that last bolded sentence, which is the most critical point. The U.S. does not “print” money. All money is lent into existence, as we continued explaining in that post.

"This means that the growth of the money supply closely follows the economy’s growth. When businesses expand, hire, and invest, banks extend more credit, and the money supply grows. Conversely, when the economy slows and loan demand weakens, money supply growth contracts, regardless of how much the Federal Reserve expands its balance sheet. We saw this after 2008: despite unprecedented quantitative easing, money growth and inflation remained subdued because banks hoarded reserves instead of lending.

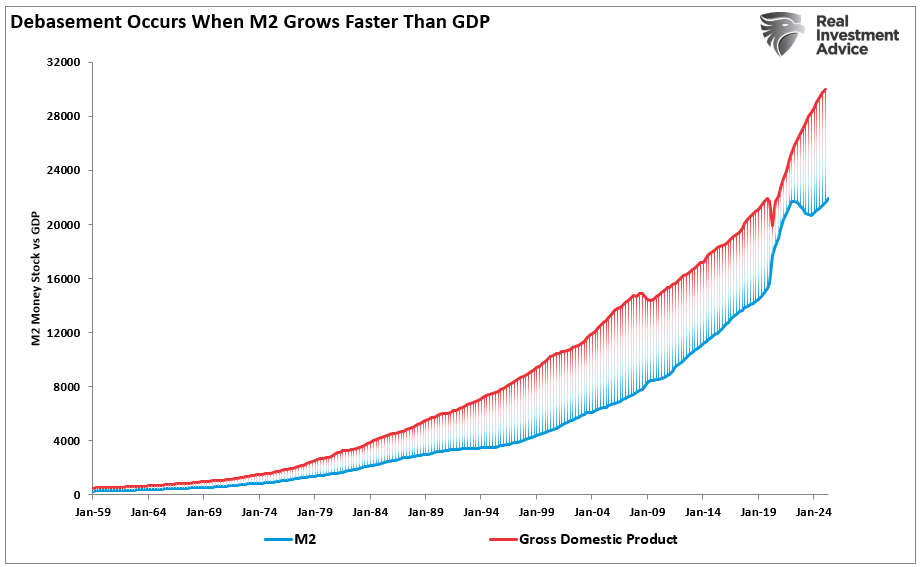

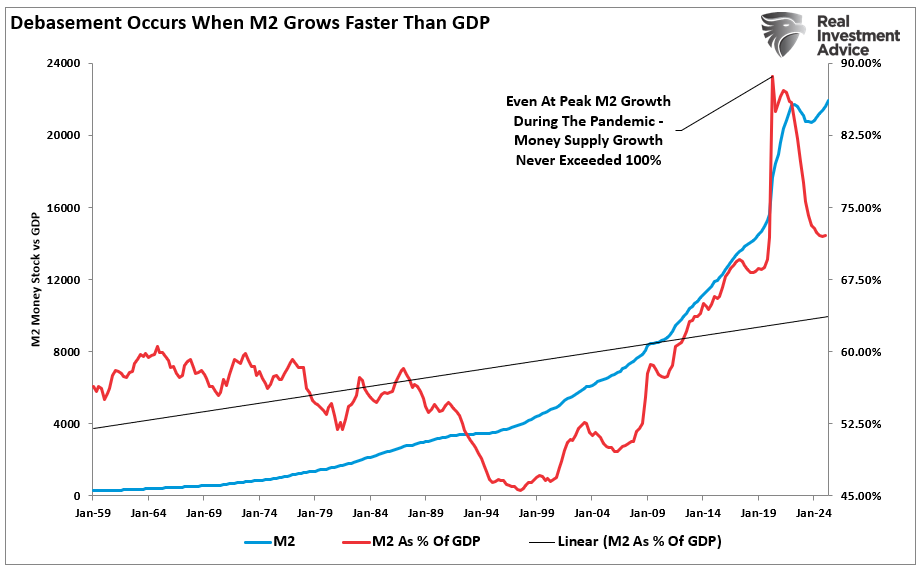

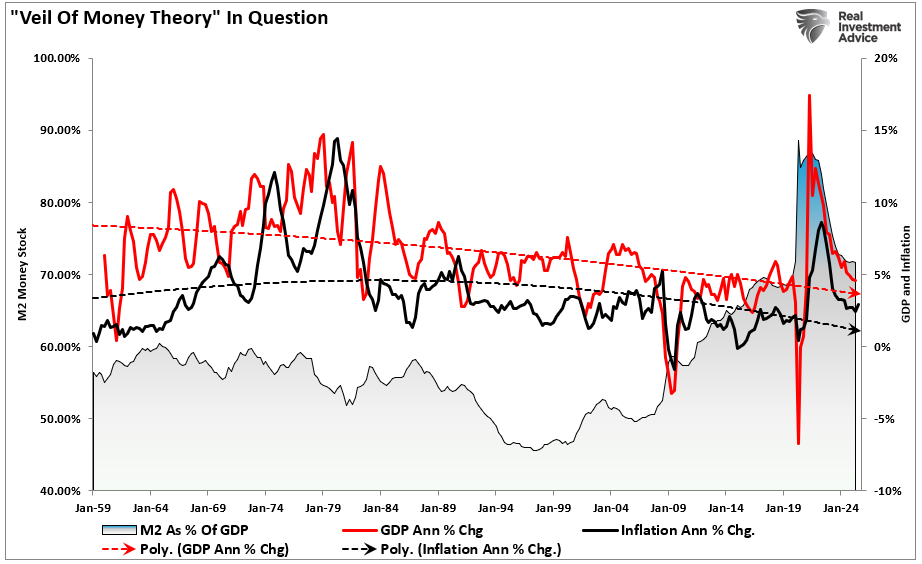

It’s easy to point to M2 charts and scream “debasement. “ However, the money supply must grow as the economy grows. If it doesn’t, deflationary risks emerge. Therefore, the key is whether money creation exceeds economic growth in a sustained way. Since 1959, the money supply has grown in alignment with economic growth."

A better way to assess this is by comparing M2 to GDP. Historically, the two have tracked closely. Even during the COVID-19 shock, M2 as a percentage of GDP remained below 100%, indicating that money supply growth was broadly aligned with economic output. Today, that ratio is falling, not rising.

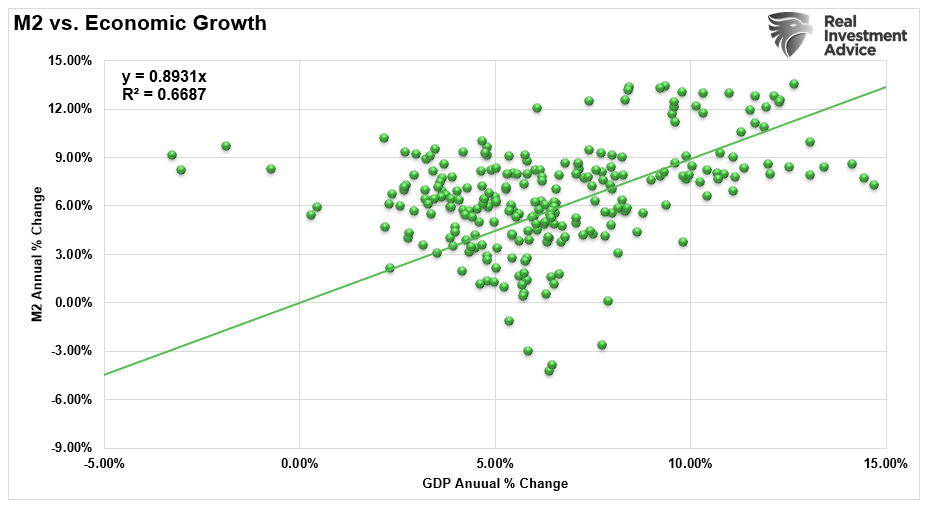

The reality is that the growth rates of M2 highly correlate with the state of the economy.

This brings us to the "Veil of Money" theory, which posits that money serves as a neutral medium of exchange, affecting only the nominal price level, but not the underlying fundamental economic factors, such as output, employment, and the allocation of resources. In this view, money overlays the real economy like a veil, and to understand economic activity, one must "pierce the monetary veil."

During the pandemic, the money supply spiked. But that’s not the whole story. Bank reserves ballooned, yet lending barely moved. Consumer demand rose temporarily due to direct payments, rather than a structural shift in consumption. Once those payments stopped and the economy reopened, that demand faded, supply increased, and inflation started to recede. In other words, the increase in the money supply did not alter the real economy; in fact, it may have worsened it.

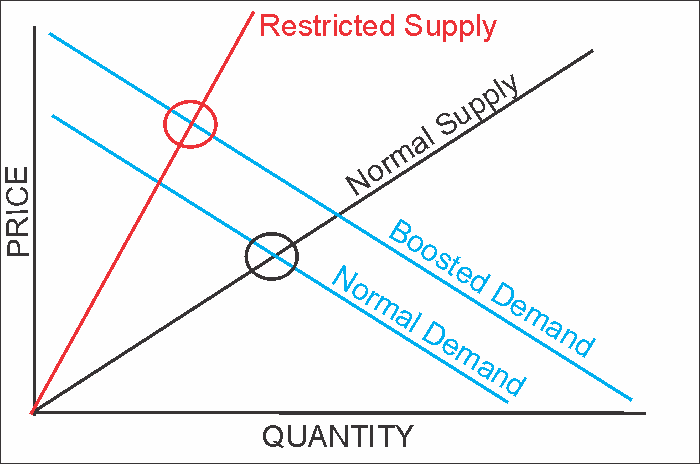

As such, the problem for the inflation alarmists is that inflation occurs only when demand exceeds supply. In a service-based, aging economy that’s already over-leveraged, such a demand surge rarely occurs sustainably.

While the inflation surge of 2021 and 2022 was real, it wasn’t systemic. It was the result of excessive government interventions in concert with global supply shocks. That combination created a short-term explosion in prices. But it was never sustainable.

The 3 D's: Debt, Deficits, Demographics

To understand why inflation alarmists have been incorrect, at least so far, you have to understand the "3Ds": Debt, Deficits, and Demographics.

Let's return to the basics of "inflation," which is simply the function of "supply and demand." Nothing more. Nothing less. As we noted previously:

"Inflation is the rise in prices due to supply and demand imbalances. Rising wages and consumer demand for products and services that grow faster than the available supply create higher prices (aka inflation). The following economic illustration is taught in every ‘Econ 101’ class. Unsurprisingly, inflation is the consequence if supply is restricted and demand increases via monetary interventions.”

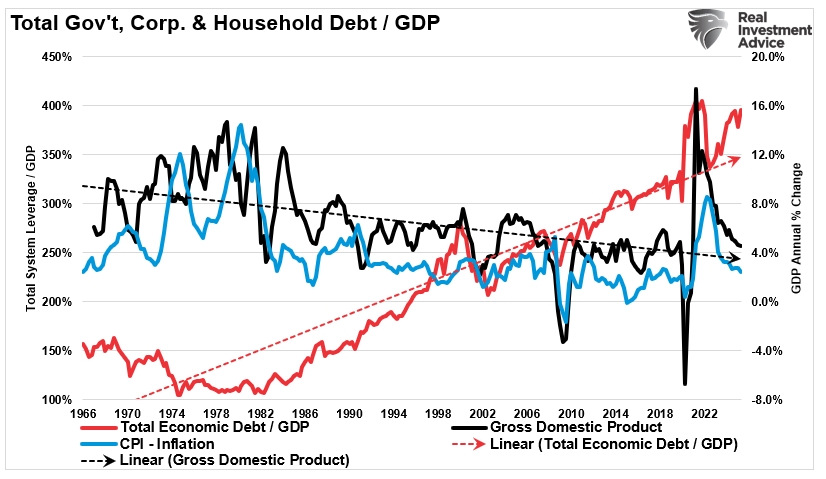

With this concept in mind, let's start with the debt. Currently, total U.S. debt, comprising government, corporate, and household debt, stands at record levels. As shown below, when that debt, as a percentage of GDP, grows, it slows economic activity as increased interest payments consume income, thereby limiting consumption and investment.

What the inflation alarmists miss is that every dollar borrowed must be repaid with future income. As more income is allocated to servicing debt, less is available for spending, which reduces demand in the economy and, as shown, leads to lower inflation. That’s why high debt is deflationary, not inflationary. Such is also why expectations of yields hitting 6% or more remain unfounded, as an economy that is dependent on debt to function can't support higher rates.

The second "D", deficits, are also problematic to the inflation alarmists' view. Annual deficits are now routine. The government borrows to fund everything from defense to entitlements to foreign aid, with the Congressional Budget Office projecting trillion-dollar deficits for the next decade. As the deficit grows, more money is diverted from productive investments into debt service, which again negatively impacts economic activity. As shown, when the deficit is reduced, it is because economic activity has increased, resulting in higher revenue for the government and potentially leading to inflationary pressures.

The long-term consequence of persistent deficits is low growth as more debt is needed to generate less output. That dynamic has played out in Japan, Europe, and now the U.S. However, ironically, while everyone hopes for lower inflation, which is economically repressive, we should be discussing how to increase inflation through stronger economic growth.

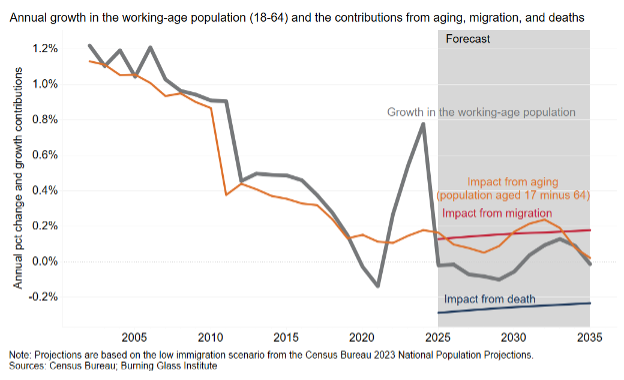

Lastly, the most overlooked driver of disinflation is the decline of demographics in the U.S. The population is aging, and the U.S. workforce growth rate is falling. Immigration has slowed. Birth rates are down. Fewer workers and more retirees result in lower production and consumption. Older people spend less. They don’t buy homes, take out loans, and live on fixed incomes, which translates to lower economic velocity.

At the same time, entitlements such as Social Security and Medicare are proliferating, absorbing an increasing share of the federal budget. That adds to debt, increasing deficits, which feeds into economic retardation.

Put all three together, high debt, chronic deficits, and an aging population, and you get structural stagnation, keeping inflation low, capping long-term rates, and reducing economic prosperity.

What the Market Is Telling You

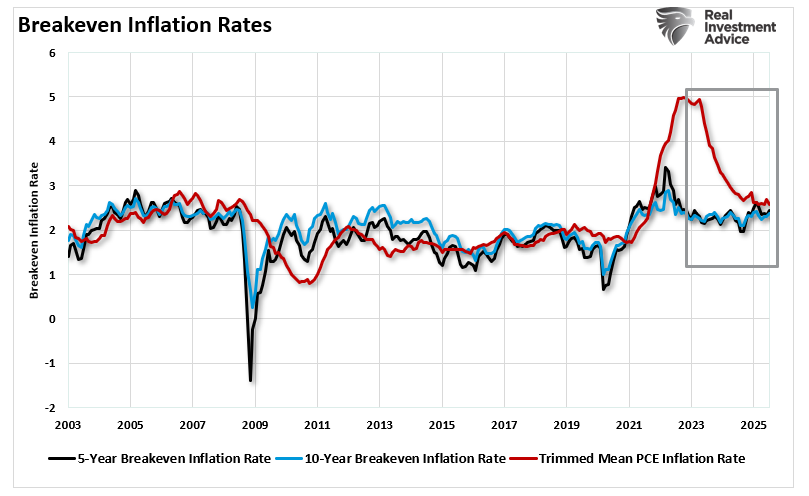

The bond market isn’t stupid. When inflation spiked, yields rose, briefly. But as soon as growth slowed and fiscal drag returned, yields fell. Long-term expectations remain subdued, with the 10-year breakeven inflation rate still near 2.3 percent. The Fed’s own projections indicate that inflation will return to target over time. As shown, the spike in the Fed's preferred measure of inflation, the trimmed mean PCE inflation rate, has returned to the bond market's view of inflation. While the Fed took a lot of heat for saying inflation would be "transient," ultimately, they were correct.

If inflation were going to stay hot, you’d see it in long-dated yields and in the breakeven rates. However, for now, at least, you don't. That’s because markets understand what Wall Street celebrities don’t: structural forces matter more than temporary shocks.

If you’re expecting another surge in inflation, you’re betting against demographics, debt dynamics, and deficit math. That’s probably going to be a bad bet.

Here’s what you should prepare for instead:

- Inflation will remain volatile but is expected to trend lower.

- Long-term yields will stay capped by debt service constraints.

- Growth will slow as the stimulus fade continues.

- The Fed will pivot again — not toward more hikes, but to rate cuts and balance sheet expansion.

Does this mean we won't ever see another rise in inflationary pressures? No. In fact, we should be hopeful for such due to economic growth that leads to broader economic prosperity.

However, the calls for runaway inflation and 6 percent interest rates are primarily a misunderstanding of the world in which we live. We are not in a 1970s cycle, but rather in a debt cycle where every dollar of growth incurs more debt, and every attempt to tighten policy leads to deflationary pressures.

That’s not a theory. It’s what the data shows. And until something changes in the structure of our economy, it’s what you should expect.

The post What Inflation Alarmists Missed In Their Warnings appeared first on RIA.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Economics,Featured,newsletter