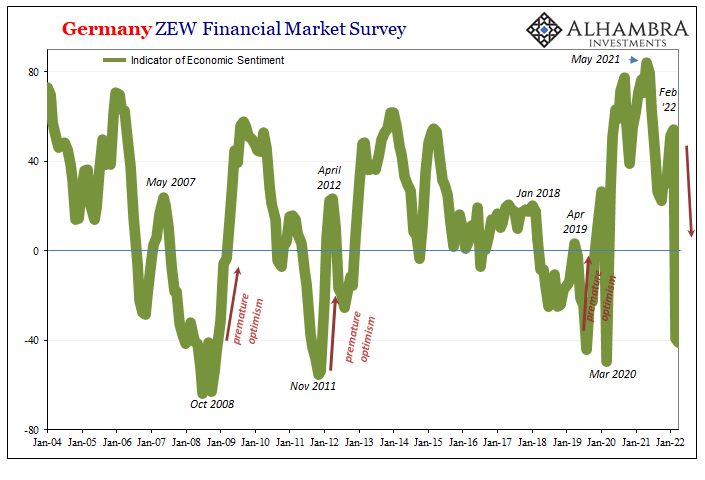

| German optimism was predictably, inevitably sent crashing in March and April 2022. According to that country’s ZEW survey, an uptick in general optimism from November 2021 to February 2022 collided with the reality of Russian armored vehicles trying to snake their way down to Kiev. Whereas sentiment had rebounded from an October low of 22.3, blamed on whichever of the coronas, by February the index had moved upward to 54.3.

It currently stands at -41.0, collapsing by nearly a hundred in just the two months of Putin’s forced misadventure. |

|

| While such reasoning makes sense for sentiment, that the narrative is and will be applied for every ill, now and in the future, for everything wrong in Germany and Europe as a whole requires more consideration.

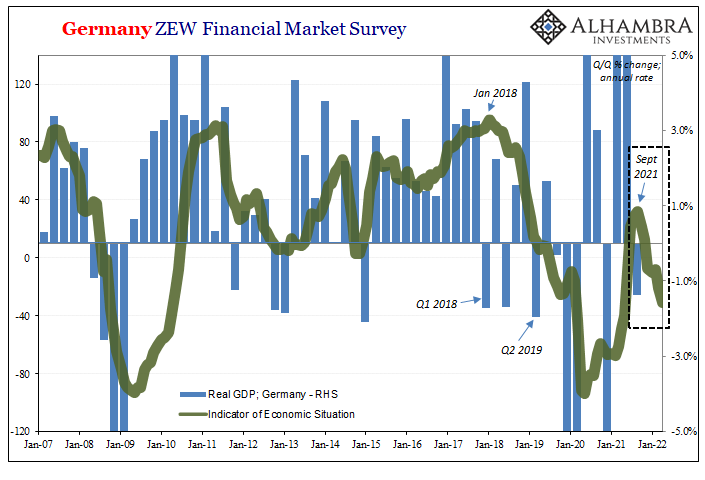

The same survey, ZEW, also tells us something very different when it comes to the German financial and commercial sectors’ assessments of their own current condition. This other index had been going the other way while sentiment had rebounded to finish 2021. In short, though COVID optimism pervaded to end last year and to begin this year before the invasion, it wasn’t being matched by the actual situation. More were telling the group that conditions were declining despite being somewhat happier about the future’s prospects (which, as you can see above, happens quite often). |

|

| The drop in the situation index long predated the current geopolitical fixation. | |

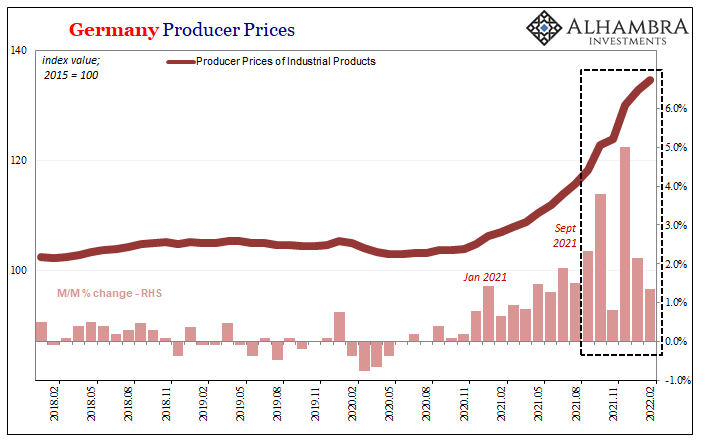

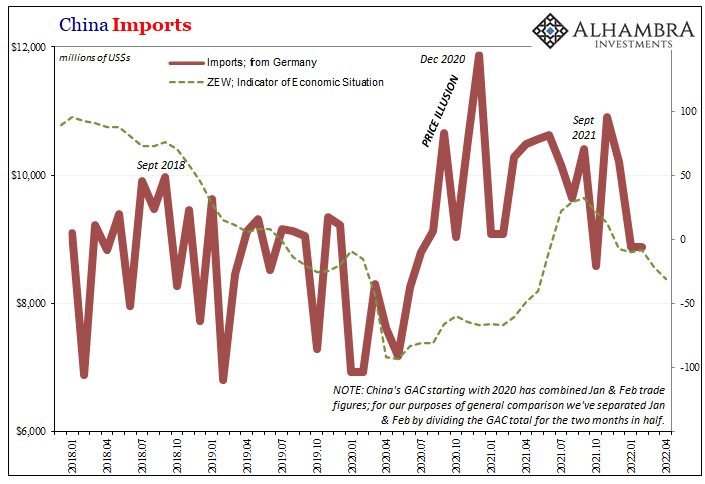

| On the contrary, there is instead a more visible therefore likelier correlation (above).

Like practically everywhere else around the world, producer prices in Germany (or Europe) were rising quickly from the beginning of the supply shock. But then around September and October, the pace suddenly and greatly accelerated further. Consumer prices in Europe like America did, too, but not nearly at these ridiculous rates. According to Germany’s deStatis, where the index of industrial prices (PPI) had been increasing at better than 1% monthly rates May through August (inclusive), in September it suddenly skyrocketed to 2.3% m/m and then right after a profoundly harmful 3.8% for October. |

|

| There would be a small reprieve in November before a truly massive 5.0% m/m increase to close out the year in December. Following this, Germany’s PPI was 25% higher than it had been in December 2020.

That this matches the direction of at least the ZEW’s current situation index may just be random coincidence. It might also represent a powerfully meaningful relationship on the industrial side where fast-rising commodities and input costs put the brakes on whatever non-COVID recovery might have been possible. Producer-side demand destruction? No Russians nor pandemic variants required. Put that together with slowing goods trade in Germany and elsewhere around the world, especially in “real” terms, and you have last year’s now-forgotten “growth scare” showing up “unexpectedly” as this year’s Global Recession Watch. |

Why should anyone outside of Germany or Europe care? Because like last time, 2018’s Euro$ #4, we saw the global macro consequences develop and then spread from there first (along with China and Japan). And the ZEW data was among the earliest warnings (for the entire mainstream to ignore).

By the time the 2s10s UST yield curve inverted in August 2019, the matter had been long before settled:

What if Germany’s economy falls into recession? Unlike, say, Argentina, you can’t so easily dismiss German struggles as an exclusive product of German factors. One of the most orderly and efficient systems in Europe and all the world, when Germany begins to struggle it raises immediate questions about everywhere else.

This was the scenario increasingly considered over the second half of 2018 and the first few months of 2019; whether or not recession. Over the past few months, however, the question has changed again.

It had definitely changed; prior to the middle of ’19, for the Germans the question went from “if” to “how long” and “how deep” at the same time the uncomfortable probabilities of “if” were being applied to more and more other places around the world.

Including, pre-COVID, the United States. He’d never admit it, but Jay Powell’s rate cuts indicate otherwise.

We look at Germany as a very possible and useful window into our own future. That means we can only hope curves are wrong this time, for the first time, and decoupling can actually become something more than just a toss-away word.

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: Bonds,currencies,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,Germany,inflation,Markets,newsletter,producer prices,sentiment,ZEW