The US Treasury’s latest “Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States” report named Switzerland and Vietnam as currency manipulators. Both countries came under scrutiny in the last report and so this week’s announcement was only surprising in that it was made by a lame duck administration that will be gone in a month.

| RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

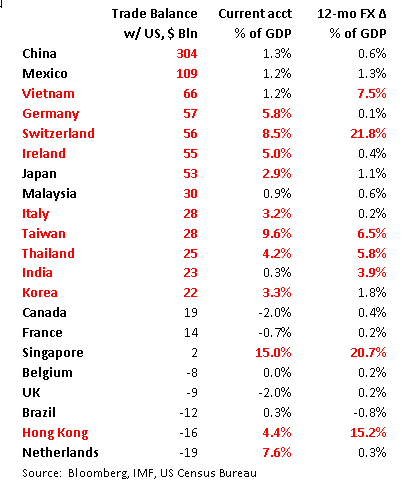

This is the first Treasury FX report since January. In previous administrations, the semi-annual reports were typically released in April and October. However, the trade war disrupted this cycle. In 2019, only one report was issued and that was in May. Under President Trump, the report has become highly politicized but that is likely to change under President Biden. Please see A Brief History Lesson below for a comprehensive look at how this report was created and has evolved, especially under Trump. The Monitoring List is now made up of China, Japan, Korea, Germany, Italy, Singapore, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, and India. Movements of note in this latest report: 1) Switzerland and Vietnam were designated currency manipulators, 2) Taiwan, Thailand, and India were placed on the monitoring list, and 3) Ireland was removed from the monitoring list. Using more recent data and IMF forecasts, we analyze these moves and highlight some that may be seen in the future. |

|

Currency manipulators: Both Switzerland and Vietnam meet all three criteria and so earned the currency manipulation designation. According to our work, both Taiwan and Thailand already meet all three criteria and should have been designated currency manipulators.

Monitoring List: China still only meets one of the criteria and shouldn’t be on the Monitoring List. German, Japan, Italy, India, Korea, and Singapore meet two criteria and belong here as well. Ireland still meets two and should not have been taking off the monitoring list. Malaysia now only meets one and should have been taken off the monitoring list.

Pass: Mexico and the Netherlands only meet one criteria. The rest (Canada, France, Belgium, UK, Brazil) meet none of the criteria. Of note, Hong Kong meets two of the criteria due to its surging FX purchases as required by the currency board. Yet HKD is by definition a manipulated (pegged) currency and so this tells us nothing new.

INVESTMENT OUTLOOK

During the early days of the Trump administration, these reports came to reflect the growing clout of the trade hawk. With the May 2019 Treasury report, the US basically put all of its trading partners on notice that scrutiny on trade imbalances would get even stronger. As it noted, “Treasury’s goal in adjusting the coverage of the Report and these thresholds is to better identify where potentially unfair currency practices or excessive external imbalances may be emerging that could weigh on US growth or harm US workers and businesses.”

With the August 2019 intra-report move on China and now the intra-report reversal, US trade policy became even more unpredictable. The Treasury FX report could no longer be viewed as an objective arbiter. Instead, it became a cudgel that can be used in a discretionary manner against our major trading partners. While US-China tensions eased after the Phase One deal was signed, it seems that trade tensions with its other trading partners would only pick up under a second Trump administration.

And that is why we see no direct investment implications. Simply put, this move was a last gasp move by a lame duck administration. Janet Yellen will become Treasury Secretary in a little over a month and we cannot imagine she will take a similar approach. Yes, President-elect Biden has pledged to remain tough on China, but the approach will likely be more multilateral and much less bilateral. This multilateral approach may actually hurt China in terms of isolating and sanctioning.

We believe Treasury has great leeway in dealing with countries named as currency manipulators. That is, Treasury can very likely refrain from any punitive measures. Instead, it can choose to work with each country to resolve any issues. It seems clear to us that under the Biden administration, a more cooperative approach will be taken and so global trading rules and such are likely to be more predictable than under the Trump administration. Overall, that is a positive for EM and other export-dependent economies.

A BRIEF HISTORY LESSON

The Treasury FX report to Congress was mandated by the “Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988.” This legislation originally stemmed from an amendment proposed by Representative Dick Gephardt that would require the US to examine the policies of countries that had large trade surpluses with the US. To put it bluntly, the legislation was a response to the deteriorating trade position of the US. Many politicians blamed foreign trade barriers rather than domestic factors for this deterioration.

The initial report to Congress on “International Economic and Exchange Rates Policy” was meant to fulfill the process set forth in the legislation. Under Section 3004 of that act, “The Secretary of the Treasury shall analyze on an annual basis the exchange rate polices of foreign countries, in consultation with the IMF, and consider whether countries manipulate the rate of exchange…..for purposes of preventing effective balance of payments adjustment or gaining unfair competitive advantage in international trade.”

At that time, Treasury examined five areas of concern to decide if a country was guilty of currency manipulation: 1) external balances, 2) exchange restrictions and capital controls, 3) exchange rate movements, 4) changes in international reserves, and 5) macroeconomic trends.

The Treasury FX report was later amended by section 701 of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015. “The 2015 Act requires that Treasury undertake an enhanced analysis of exchange rates and externally‐oriented policies for each major trading partner that has: (1) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States, (2) a material current account surplus, and (3) engaged in persistent one‐sided intervention in the foreign exchange market.” Treasury noted that “Because the standards and criteria in the 1988 Act and the 2015 Act are distinct, it is possible that an economy could be found to meet the standards identified in one of the Acts without being found to have met the standards identified in the other.”

In the April 2016 report on “Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States,” Treasury laid out the specific thresholds for the three new criteria regarding currency manipulation: “(1) a significant bilateral trade surplus with the United States is one that is at least $20 bln; (2) a material current account surplus is one that is at least 3% of gross domestic product (GDP); and (3) persistent, one-sided intervention occurs when net purchases of foreign currency are conducted repeatedly and total at least 2% of an economy’s GDP over a 12-month period.”

No trading partner was found to satisfy all three criteria in that April 2016 report and so none were named currency manipulators. However, Treasury created a Monitoring List of the countries that fulfilled any two of the three criteria. This list initially contained China, Japan, Korea, Taiwan, and Germany. The October 2016 report added Switzerland, while the October 2017 report dropped Taiwan. India was added to the monitoring list in the April 2018 report.

Starting with the May 2019 Treasury report, the US assessed all trading partners whose bilateral trade with the USD exceeds $40 bln per annum. Before, Treasury assessed the 12 largest trading partners plus Switzerland. Using 2018 data, this new group contains 21 countries that account for more than 80% of US goods trade. The eight new countries assessed are Ireland, Vietnam, Malaysia, Thailand, Singapore, Belgium, the Netherlands, and Hong Kong. They join the previous group of thirteen that included China, Mexico, Japan, Germany, Italy, India, Korea, Canada, Taiwan, France, the UK, Brazil, and Switzerland.

In May 2019, Treasury also adjusted the criteria for being named a manipulator. The threshold for the current account surplus was lowered from 3% of GDP to 2%. The criteria for persistent, one sided intervention was also modified. A country will now be flagged if net purchases are conducted in at least 6 out of 12 months (vs. 8 previously) and these net purchases total more than 2% of GDP over a 12-month period.

Lastly, the Trump administration expanded its ability to penalize currency manipulators in May 2019. Not surprisingly, this centered around the Commerce Department proposing countervailing duties that could be imposed when foreign governments “subsidize” their exports by deliberately weakening their currencies. If a country were identified as a currency manipulatpr, the Commerce Department will determine whether a tariff should be levied. That process would involve an investigation by both the Commerce Department and the US International Trade Commission. Not for nothing did President Trump proclaim himself “Tariff Man.”

In August 2019, Treasury named China as a currency manipulator. This unprecedented intra-report designation came just months after the May 2019 report that said China warranted continued placement on the Monitoring list. What was also unprecedented was the fact that China only met one of the three criteria at the time of designation. The move came during the height of the trade war tensions and was clearly meant to intimidate China.

Indeed, reports from August 2019 suggested that President Trump made the choice to name China, leaving it to his staff to complete his directive. Treasury did so officially by citing the Omnibus Trade and Competitiveness Act of 1988. This unilateral decision seemed to supersede the three objective criteria set forth in section 701 of the Trade Facilitation and Trade Enforcement Act of 2015 (see A Brief History Lesson below). Yet countervailing duties were never levied. Why not?

The January 2020 report no longer named China as a currency manipulator. At that point, the Phase One trade deal had been largely agreed to and so there was no longer any need for tariffs. For the record, Treasury directly addressed the inconsistency by noting that “Because the standards and criteria in the 1988 Act and the 2015 Act are distinct, an economy could be found to meet the standards identified in one of the Acts without being found to have met the standards identified in the other.” More specifically, “As a further measure, this Administration will add and retain on the Monitoring List any major trading partner that accounts for a large and disproportionate share of the overall US trade deficit even if that economy has not met two of the three criteria from the 2015 Act.”

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next postTags: Articles,developed markets,Emerging Markets,Featured,newsletter