The key word in the whole thing is “bias.” For a very long time, people working in and around the finance industry have sought to gain tremendous advantages. No explanation for the motive is required. Charts, waves, technical (sounding) analysis and so on. To many dispassionate observers there was always this sort of improper religious fervor to it rather than honest science.

The first major figure who had sought to change all that was the unfortunate Louis Bachelier. While Eugene Fama has been proclaimed the father of modern finance, and we’ll get to him in a minute, it was actually Bachelier – as Fama even noted in his seminal 1970 paper Efficient Capital Markets: A Review of Theory and Empirical Work, the one which had pointed his career in the direction of eventually sharing the 2013 Nobel Prize in Economics.

At the dawn of the 20th century, it had been Bachelier not Fama who had first begun Wall Street’s move toward the efficient market viewpoint. As I recalled five years ago in the midst of the non-random if “unexpected” setbacks produced by Euro$ #3:

Though Bachelier’s instructor was none other than physicist Henri Poincaré, such was the novelty that his vision wasn’t immediately appreciated, taking instead decades to finally get some due. This despite his attempt to retrieve the mathematics of Brownian motion in the service of trying to quantify financial speculation that actually predated Einstein’s celebrated work by five years. Eventually, that dissertation became published as Théorie de la Spéculation and came to form the basis of what are now the modern theories of finance.

Set off to the side for more than half a century, those theories were given new life in the 1960’s by Paul Samuelson and Benoit Mandelbrot (among others). These men had written convincingly in support of stock markets being a “fair game”; that is, the information embedded within all stock prices is available to all who play. There are no unfair advantages to be taken advantage of.

If that is so, then we would expect to find a beautiful randomness to the behavior of stock prices. Without those unfair practices, how it would it be otherwise? In fact, that is what Samuelson and Mandelbrot had statistically shown; market prices did indeed appear to be randomly distributed.

All that left for Eugene Fama to do was provide the argumentative framework which might best explain and fit the experimental data much of which had already been gathered – some of which going all the way back to Bachelier. Fama wrote in his paper’s introduction:

Though we proceed from theory to empirical work, to keep the proper historical perspective we should note to a large extent the empirical work in this area preceded the development of the theory.

That theory was efficient markets – some form of it, anyway. It was taking the idea of a “fair game” market to its absolute furthest conclusion: the random walk first surmised by Louis Bachelier. The best, most succinct summary of the concept contained within Fama’s paper was actually written by another economist, Paul Cootner (who had in 1964 put together an anthology of those prior empirical studies, The Random Character of StockMarket Prices, with Louis Bachelier’s groundbreaking thesis):

If any substantial group of buyers thought prices were too low, their buying would force up the prices. The reverse would be true of sellers. Except for appreciation due to earnings retention, the conditional expectation of tomorrow’s price, given today’s price, is today’s price.

I love that quote, though for reasons that would probably make Eugene Fama flame with anger; it’s a pretty ridiculous tautology. Tomorrow’s price can’t start from anything other than today’s prices because we can’t know what will happen tomorrow. Thanks, professor.

Why is this absurd? Do I have to mention valuations? Or, in other words, the anticipated “appreciation due to earnings retention.” If buyers today think earnings retention tomorrow is going to be awesome, acting in concert on all the available information which tells them this, and tomorrow as well as a thousand tomorrows when the price is (massively) higher but the earnings are not, then that’s new information? Of course not; it may become a new fact, specifically, though one surmised and reasonably expected in advance of tomorrow.

As I wrote right at the start, the issue is one of bias. What if, stay with me here, there existed this powerful monster which could at the flip of a switch make tomorrow’s earnings much better than they might have been otherwise? Efficient markets, investors in the stock market would bet on that “information” today, right now – even if it never actually happens because today’s price is today’s price!

Who gives a sh%& about tomorrow, we’ll just deal with any “new” information then! What a dim view (acknowledging the risks of making this a teleological discussion about exactly what counts as “information.”)

Because they are biased. Furthermore, that bias begins to take over even the formerly unbiased who witness this self-fulfilling prophecy and then begin to either believe it for themselves or trade in sympathy with it without ever intellectually buying it (the Fed’s a powerless joke, but since everyone else believes Don’t Fight the Fed! I’m going to be buying when they’re buying anyway).

The game still looks fair from the inside because the haughty monster is on its outside trying to game it for its own purposes that have nothing to do with profitable trading. So long as that monster remains a key focal point of bias and belief, the tautology remains firmly in place.

Most people ascribe the monster’s power to the equally mythic “printing press”, that whenever a central bank “prints” “money” through the power of QE or some other large-scale asset purchase (LSAP) it just hands cash to Wall Street (it doesn’t). Once in hand, we are meant to presume those banks just buy equities with the funds.

|

Don’t expect Eugene Fama to agree, however. Coming at the Fed’s expectations management program from a very different angle than I do, he still arrives at the same conclusion. Because it’s the only conclusion to arrive at consistent with every last bit of evidence. Though, I have to admit, a few days ago he put it far more eloquently than I ever have:

So, then, what’s going on in the stock market (according to Fama)?

If the market is efficient and therefore forward looking, just how forward must it today be looking? That’s the thing, there are supposed to be earnings involved in here somewhere even if there’s a random walk distribution to how those get evaluated and priced. The stock market has gone higher and higher, with all due respect to Dr. Fama, predicated on the monster we are taught to believe exists at its center being able to create that better future for corporations to produce within. |

The Real GDP Problem, 1988-2018 |

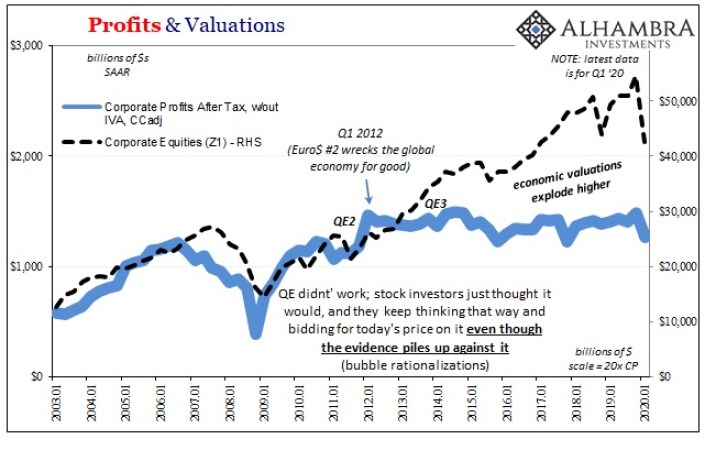

| In other words, to stay with efficiency stocks have to be early not wrong. And if that’s so, again, just how early must they be? Valuations as well as the actual economic conditions over the prior dozen years, especially where profits and earnings have been concerned, don’t indicate a rational expectation for anytime soon.

Markets have to be, then in Fama’s view, efficiently posturing (way) in advance of “earnings retention” that might happen perhaps sometime in the 2030’s (my podcast co-host Emil Kalinowski is already on record in favor of this scenario, when we get to Part 3 of Ep. 21)? If we’re lucky. |

Case Study in Missing Growth & Profits, 1983-2018 |

| Because we’d have to be lucky since it is very well established otherwise that the Fed’s not going to be able to do the things it has biased most of the market’s participants into believing it can. As these economists have said, the conditional expectation of tomorrow’s price, given today’s price, is today’s price. And today’s price is based upon an entire empirical history of such monetary policy failures that Eugene Fama just can’t buy.

Maybe-tomorrow-it-will-work-though isn’t exactly the stuff of efficient markets, but it’s good enough anyway that Fama at least can see through the monetary policy bullshit and arrive at this one truth, even if coming at it from a very different direction (I’ll get to that later). I non-randomly expect this to be the basis for some tomorrow’s price. Unlike the Fed bias, the eurodollar system has already imposed its own far more real biases – on both economy and stocks, if far more the former than the latter. |

Profits & Valuations, 2003-2020 |

Full story here Are you the author? Previous post See more for Next post

Tags: currencies,earnings,economy,Featured,Federal Reserve/Monetary Policy,federal-reserve,Markets,Monetary Policy,newsletter,profits,QE,stocks